A Forest’s Drive for Motion: Acoustic Ecologies and the Sonicity of Labour

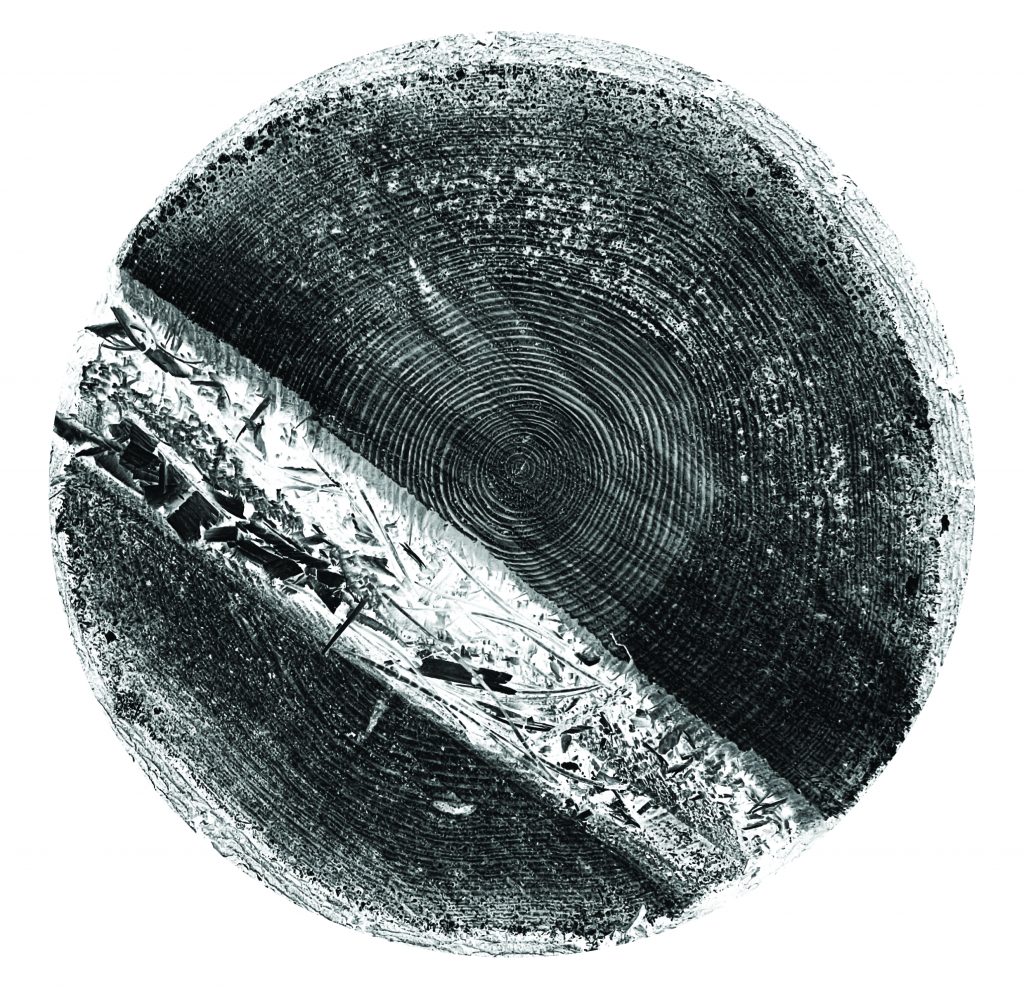

Currents (2020) is an installation by Lina Lapelytė and Mantas Petraitis which brings together over 2000 pine logs to form a floating island on the water by the 2nd Riga Biennial’s (RIBOCA2) main venue, Andrejsala, reminiscent of timber rafting on the Daugava River. This monumental structure reflects on the sonicity of labour and the relationships, ideologies and sensitivities that arose over centuries of Riga’s involvement in the timber industry.

Western philosophies have associated forests’ rootedness with their immobility¹. Yet, we know that after the last glacial age, as temperatures began to rise, birch and oak trees began marching northwards, bringing with them their associated flora and fauna. From early on, humans understood forests’ drive for motion: they converted their timber into fire, their logs into rafts, and their fibres into paper scrolls. In its boundless movement, bark was converted into nourishment, transport, housing and narrative. For those who are troubled by our predicament in the age of environmental devastation, acknowledging the dragging march of a forest renders movement, decay and regeneration as fundamental features of our rapport with the world.

Where woodlands expand a large surface of the land, history and economic development become inherently tied to the movements of trees, thicket and timber. On the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, Latvian woodlands cover over half of the country. Since the Middle Ages, its forests have supplied Western Europe with timber for ships and buildings. In the 1930s, Latvian timber export represented 10% of the global market. While it provided economic protection, the forest also occupied a privileged space in society having harboured Latvians who fled to the woods to seek refuge inside its bark and atop its canopies during conflicts between the Russian, German and Swedish empires. Today, forests represent the nation’s future as new markets emerge for biomass energy projects and biofuel.

Flowing westward over one thousand kilometres in a great arc through Russia and Belarus and discharging into the Gulf of Riga on the Baltic Sea, the Daugava, played an important role enabling Latvian forests’ economic flow. Referred to as the ‘highway of rafts’, the Daugava was central to the circulation of timber until the river was dammed to build Riga’s hydroelectric power plant in 1974. Before, thousands of logs would be brought together on water, forming immense rafts carried by the currents and guided by raftsmen. The latter understood forests’ drive for motion and learned to cohabit with the river, working with or against the current to carry the timber. In the apparent stillness of the forest and in the loud of the Daugava, raftsmen communicated through song. Their songs boar witness to their working conditions while capturing the acoustic ecologies of forest and water mobilised by the hope of economic development.

Departing from this global history of labour, Lina Lapelytė and Mantas Petraitis’ sculptural and sound installation Currents investigates how the pulsing rhythms of raftman’s songs are central to capitalist modes of production. Composed of 2000 pine logs arranged to form a floating island in Andrejsala, a decommissioned industrial port in Riga, alongside a sound installation playing through the outdoor warning speakers, Currents proposed a mode of listening beyond the ear, a visual and sonic composition attentive to the sonicity of raftsman’s labour and its more-than-human languages.

Walking through the ruined industrial port hundreds of logs drift at bay either too crooked or too thick to be used as wood for cutting before continuing its journey westwards by land and sea. A loudly resounding meter demands our attention. As I tune into its steady compass, I hear a combination of poetry and singing that flirts with the raftsman’s songs. A female voice describes their rhythmic arrangement, from a seemingly disorganised percussive amalgamation, where the narrator tells us ‘everything belongs to Man’, to the law-like sound of clock-time. The female voice is joined by others, initially in acapella and later to the low-fi sound of electronics. In low tone, as one might imagine the raftsman’s songs to have been, they softly repeat ‘they were going on and on and on, the super young and pretty old.’

For the documentation of the installation, filmed on the deck that traversed the bay of pine logs, Lapelytė was joined by two singers who in unison turned their heads in circular motions in a gesture close to slow headbanging. In the performance itself, their voice goes out of words and into sound. The wood crackling at their feet and the river underneath them join in as a chorus of concatenated sounds, as if singing in unison the law-like sound of clock-time.

The socio-politics and sonicity of labour

Since the invention of the bell tower, as Lewis Mumford shows in his seminal Technics and Civilization, the measurement of time ushered a particular rhythm into the life of the craftsman and the merchant². In the nineteenth century, a wider debate about the management of time focused on how to organise labour and balance economic development with workers’ rights. Rhythm was at the centre of this project. Echoing modern theories of resonance in the fields of acoustics and musicology during the formative period of modernism around the 1900s, the ear was simultaneously linked to the perception of time. These transformations profoundly impacted how meters, alongside clocks, organise time.

During this period, German economist Karl Bücher’s Arbeit und Rhythmus [Labour and Rhythm] published in 1896 extensively reprinted until 1924, sought to uncover a relation between labour and rhythm by analysing work songs as well as performance in so-called premodern societies throughout the globe. Bücher examined work songs of ancient societies in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East and in relation to the work performed, such as milling, digging, lifting, carrying, scrubbing, and so forth. Despite his ethnographic efforts, Bücher was unable to conclude a singular musical rhythm that could have dominated relations between song and labour. Yet, he nevertheless observed an ‘original unity’ in which ‘labor, play, and art blended into each other’ to establish ‘rhythm as an economic principle of development.’³

According to Bücher, this unity was possible to the extent that in song, the worker did not perceive the commodity-form produced by their labour as alien to his or her expectations of life. For the economist, song was a relational language that allowed rhythm to stand as an emancipatory alternative against the law-like authority of clock-time. In modern management theory, however, his study supported a view of rhythm said to taxonomise time. At this time, chronophotographic investigations of labour processes inaugurated an international science of work. Frank B. and Lilian M. Gilbreth’s time and motion studies, for instance, used chronophotography and cinematography to closely analyse work processes in order to determine optimal task management while reducing externalities to a minimum.

While conventional views of time describe it as forward-moving, one-dimensional, universal and made up of spatial successions, musical time shows us how it is made up of tempos, rhythms and syncopations that ward off, suspend, accelerate and re-organise our perception. I suggest that workers’ songs alongside other evolutionary tempos might help us reframe our socio-political chronologies. Indeed, raftsman’s songs strengthened working class solidarity and more-than-human kinships through sound and ritual. Sang to the metre of synchronised axes cutting into the wood and at the tempo of deforestation, these songs tell us about enmeshed dramaturgies of time.

Rhythm’s inherent capability to facilitate a shuttling across temporality and in delays, repetitions, glitches and overlays urges us to re-engage with raftsman’s songs and their productive rhythms as tools for interrogating the foundations of modernity and capitalist development. For Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung,

‘Sound is considered as a testament of and survival device for workers, one that is imbued with necessity, hope, and love, as it exists as the noise of tools and machines, as a vibration of exhausted bodies, as chants of protest, as laments and elegies of loss and pain. (…) These range from alleviating the pain of working under extreme conditions such as plantations, waste dumps, or 3 miles down the earth in the mines, as Gil Scott-Heron points out. Songs help to increase and survive the requests of high productivity by keeping with the rhythm of the work, or reducing the sentiment of boredom like it would be the case while sowing, picking cotton, mowing the lawn or cooking.’⁴

As Ndikung points out, the sonic opens up the effects of practices that divide subjects from objects, exposes the routes of racial capitalism and it renders hearable modernity’s organisation of labour-time. In my research around what I term the ‘sonic continuum’, I look at how non-linear and syncretic sonic histories manifest our understanding of time and, by extension, our experience of the world, as constantly seized by the language that describes it. In an effort to de-essentialise the ear and denaturalise the historical construction of time as a category of modern Western knowledge-making, I try to grapple with how time controls representation and what consequences this might have for the field of visual cultures.

Thinking through sound, silence and speech, whose voices are heard, who listens, and by what means, visual artists have explored the sonic as the articulation of tempos and cycles of time. By assembling multiple, overlapping timeframes, artworks and installations such as Currents propose rhythm as a relational language, which might inspire a sense of co-belonging between humans (historically recent and distant), non-humans (large and microscopic), and environments (near and far). In Currents, the sonic movement away from representation into expression serves as the stage for a poetics of temporal disjuncture revealed in mechanical motions of repetition and staged as tempo and text.

Temporal Disjuncture

The role of sound and phonic substance in Currents orients us towards an ethics of listening that enables us to recognise not only their shared forms of being and belonging with one another, but also with the river and the forest as they relate to gender, ecology and life under capitalism. Currents enmeshes the day-to-day struggles of raftsmen and their life-long and oftentimes generational connection with the surrounding watery and vegetal elements, with the accelerated tempo of economic development, the slow violence of deforestation and the longer scale of environmental change. By creating temporal complications in a rhythmic episode that disturbs the linear time of capitalist production, the installation puts forth renewed kinships and a longer tempo of auditory awareness.

Movement, circularity and repetition are the rhythmic aesthetics that Lapelytė and Petraitis’ monumental installation tuned into, offering us a take on the expressive dynamics of listening across auditory registers of human and non-human solidarity across capitalist development. Inasmuch as deforestation and extraction are expressed in the law-like meter of clock-time, the raftsman’s songs also sound out other possible connections between human, river and forest. At this temporal disjuncture, Lapelytė and Petraitis’ collaboration allows us to listen to the movement of forests alongside the tempi of rivers and the currents of economic development, conjoining our senses with the unsound and the silenced to imagine new solidarities, aural alliances and forms of attunement.

Sofia Lemos is a curator, writer, and researcher working on the curatorial as a mode of enquiry that melds perceiving, sensing, feeling and knowing as knowledge-making practices. Rethinking sites of knowledge in relation to their conceptual emergence, unresolved histories and multidimensional narratives, she explores how thinking through and with contemporary art opens up other modes of being and belonging based on experience, sensation, embodiment, plurality and positionality. She is the inaugural Curator of a new institute for arts, environmental and social justice established by Thyssen Bornemisza Art Contemporary (TBA21) and Curator of Public Programmes and Research at Nottingham Contemporary, where she has initiated numerous collaborative research programmes, including the multi-platform commissioning series Sonic Continuum (2020-ongoing). Recently, Lemos was Associate Curator Public Programmes of the 2nd Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art – RIBOCA (2020).

- See, for example, Michael Marder, Plant Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life, New York, 2013; Luce Irigaray and Michael Marder, Through Vegetal Being, New York, 2016; and Emanuele Coccia, The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture, Cambridge, 2018.

- Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization, Chicago, 2010 [1934]), p.13.

- Karl Bücher, Arbeit und Rhythmus, Leipzig, 1909 (1896), p.413.

- Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, ‘Force Times Distance: On Labour and Its Sonic Ecologies’, Sonsbeek 20–24 no.1, June 2020. https://www.sonsbeek20-24.org/en/editorial-room/issue-one/force-timesdistance-labour-and-its-sonic-ecologies/, accessed 23 June 2021.