A Week in August

Revisiting, rethinking, and contemplating: memories, monuments, and research in former Yugoslavia.

In 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic, a new monument was erected very close to where I live in London. It provided an opportunity for the local community to gather and celebrate one of the rare monuments dedicated to women, since according to the Public Monuments and Sculpture Association (PMSA), there are over 828 statues in the UK of which, only 174 are of women (2018).¹ But this sculpture, placed in the middle of the Newington Green, a neighbourhood that has recently become a popular place for middle class creatives and that was that same year the site of Black Lives Matter demonstrations and gatherings of solidarity with Palestine, caused outrage when people laid eyes on the odd artwork. Dedicated to a pioneering eighteenth century, local feminist, A Sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft by artist Maggie Hambling, presented itself in a very bizarre form that could hardly be understood as a celebration of this author and icon. My first impression was absolute confusion: what is this attention seeking large silvery blob? Only the conventional plinth it sits on continues to remind us that we are looking at something of supposed importance. The structure looks a little like someone had used silver spray paint to cover a styrofoam blob. On top of the blob emerges the figure of a miniature naked female. It could easily be mistaken for a mythical character or a folk tale of small nude people that haunt the neighbourhood. Many residents decided to protest the inappropriateness of the naked miniature which is meant to stand as a celebration of the feminist icon, yet it still remains in place and has become part of the landscape that is now ignored, and I imagine even tolerated by some (Brown, 2020). What is yet to be seen, is how this structure will age and whether it will eventually be reconsidered. The question of its ageing, its decay turns us back to thinkers such as Alois Riegl (1982) and John Ruskin, whose thoughts on preservation created a shift in the way we observe and appreciate historical sedimentation. Should the naked miniature simply be allowed to deteriorate or is there something about notions of accelerationism that is somewhat necessary in the 21st century, that seeks a different kind of sedimentation? If there is a need for the reconstruction of thoughts of the twentieth century regarding our building and removal or even repurposing of monuments, would now not be the time for these shifts to take place?

In a BBC news report² (2016), which is just under four minutes long, we hear the story of a woman who was raped repeatedly and held as a hostage in a hotel that was used as a rape camp during the 1990s Yugoslav Wars. Towards the end of the clip, she is asked what she thinks about the space that has now returned to its original purpose, a hotel. She responds that the place should be torn down and the land to remain completely barren.

We are often in conflict between the need to destroy and remove all memory and reminders of horrific events of the past and to remember them as a need to caution the future generations of the catastrophic potential of wrong paths and turns. There is no right or wrong answer, especially in present day, when we are confronted with ever increasing and overpowering mnemonic tools. These are documentaries, movies, books, archives, artworks, music but also plaques, temporary memorials, performative ceremonies, demonstrations, all of these are now our tools, and we cannot often escape them even if we might like to. Forgetting has become a luxury that many colonial nations seem to have taken for granted and are now regretting having done so. With artists and scholars on missions to uncover the painful events of the past, we seem to be battling for who might uncover which stone first, and which stones might be buried forever.

In this climate of ‘not forgetting and not yet forgiving’, we encounter the battle for public space. While there may still be barriers as to who has the right to this space, eventually those barriers will fall and there will be a need for a democratic division of power dynamics or maybe things will just stay the same; seemingly democratic, seemingly tolerant to the needs of those, whose histories have not been addressed, who remain to this day oppressed. The regurgitated notion of the shifting role of the monument is as evident as it is inevitable. We all seem to want to find further meaning in a tradition that seems familiar and globally understood. Yet, these shifts that we long for don’t quite align with the current negotiations taking place.

While there was a huge shift in Germany in the 1980s and 1990s with what the US Holocaust scholar James E Young termed as the ‘counter-monument’ (1992), since then we have been somewhat taken aback by the slow-moving debates that brought us not only to Covid-19 but more importantly to a period of unimaginable changes. We call it the toppling of monuments, but theorist Gal Kirn referred to it as historical revisionism (2020), though it is clear Kirn may not have perceived it as a necessarily negative aspect of the movement to reclaim not only public spaces but historical narratives, as is often regarded. We are accustomed to understanding revisionism as a necessarily negative form of rewriting, reconstructing and reintroducing history but in this case, it is more like repairing a broken or twisted narrative; one that either needs to be repaired or untwisted. Either way, the endgame would be that it is seen in its entirety. And when thinking about revision in this form, how can we not continue or even begin to idealise the need for transformation rather than stability. Stability seems to be a preferred solution to acknowledgement yet without it, any kind of stability will not be long lasting. While with acknowledgement, a state of stability will no longer be needed, instead a further exploration of various nuances of historical thoughts and remembrance will allow for it to become a place of ever-changing reflection and interaction.

Contemplation on the activity and presence of a monument doesn’t happen in isolation, it is always part of a collection of understandings, discussions, thoughts, and histories that, together, inform what we are witnessing. When thinking about the removal of contested monuments and memorials, the building of new ones, and the fascination around how we are to deal with understanding what the role of these structures [tangible or not] is, we must first and foremost think about whom we are building for, with what intent, and who is making those decisions. We pride ourselves in our seemingly democratic ways of organising our societies, but we have done very little to address the democratisation of our histories and collective memories. These have become a thorn in our heel. Academic and artistic research has recently embraced more openly critical discourse on the topic, but can such approaches lead to reconsidering the position monuments and memorials play in the formations of national identity and the developing struggle for their presence in public space. Who is responsible? Why? And does that responsibility also extend to accountability?

This year will mark 22 years since the collapse of the Former Federal Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia. Back in the early 1990s, the world, particularly Europe, gasped in shock at the atrocities being committed, particularly as the war split many friendships, families, and acquaintances. The question of commemoration, remembrance, and collective memorialisation became part of everyday life throughout the many years of the Yugoslav Wars.

A week in August (2014), was envisioned as the first in a series of works relating to memorialisation and dilemmas of monument building across former Yugoslavia. As it developed for my doctoral thesis, it behaved less as an artwork and rather as a way to begin.

It is built from a convention of auto-ethnography and notions of the journal or travelogue as a method of approaching artistic investigations into and reflections of post conflict spaces. Set out as a project to investigate the idea of the monument, the ‘trip’ or ‘field- study’, which took place over the course of seven days in the former Yugoslavia, also intended to create a platform for initiating relationships with some of those involved in the processes of reconciliation and commemoration there, and document encounters with memorialisation projects, within the limits of a short trip. Crossing a large part of former Yugoslavia, the trip was punctuated with meetings across the many cities that were visited. Neither my cameraman nor I, had ever made a trip across former Yugoslavia. We were prepared to document our trip and encounters however, we could not predict that our inexperience, of never having worked as journalists or researchers in conflict or post-conflict spaces, would inhibit us from being able to engage with the environment in the way we expected. Both coming from Slovenia we had never experienced the horrors of the wars and were too young to have felt the fear of uncertainty and the looming sense of violence that swept the region when the wars began.

Using an auto-ethnographic approach seemed to be the only way of portraying a conscientious image of a situation in which I was an outsider and would remain as one. As the discussion of appropriation lurks in the shadows of many debates surrounding artistic practices and approaches to dealing with trauma, I was well-aware of my politicised position as the artist voyeur.

The autobiographical and auto-ethnographical perspective has been explored in great depths by a variety of artistic practices. Since the collapse of the former Yugoslavia, many international and local initiatives have formed platforms to explore reconciliation and peacebuilding. Former Yugoslavia has several artists known both nationally and internationally, working in different mediums, that have acted on these boundaries of using their personal experience to engage with representations of conflict. These types ofmpresentations are common in artistic practices and allow for the artist to present a multiplicity of interwoven stories, facts, critiques and commentaries on situations and topics. They are as much their own personal archives as they are our collective memories. Reflecting for a moment that is frequently debated in relation to representations of trauma in post-conflict spaces: what about the artworks emerging from research but not personal or shared experiences of that particular trauma? What does it mean for an artist to work with conflict not experienced first-hand? This comes back to the question of who has the right to decide on the formats, figures and events of memorialisation? These queries are all rooted within the same historically contentious debate; of political, social, and cultural power.

A week in August elaborates on this position and reflects on how I attempt to maintain a balance when allowing myself to observe and comment from the position of an outsider. And instead of creating a solely visual work, which might provoke an immediate emotive reaction, the work attempts to engage through a form of storytelling that I subjected myself to throughout the trip, therefore creating a form of re-enactment. This perhaps stems from a position that there is a general desensitised mode of observing images that has been created by a consistent over saturation of violent or painful images and that often we – those of us of a certain generation – even form immediate visual associations based on the images that were shown through mainstream media.

The outcries of the Yugoslav Wars were also hidden at times, with some of the most horrific events appearing in mainstream media because of a handful of journalists. It is because of such concerns and responsibilities regarding artworks which comment on conflict spaces that A week in August stepped away from a certain type of aesthetic. The title itself offers the first critique, describing not only the time frame but criticising what many locals have voiced as concerns about how the past and present are depicted through the eyes of artists, journalists, researchers, bloggers and NGO workers who step into the situation for a moment and feel capable of describing and depicting it to the rest of the world.

A week in August attempts to do three things; to open discussions into the continuous silent violence of the already abused and violated, then expose the issue of the impossibility of monument-building and the denial of war crimes and finally question the potential of an adaptation of the counter-monument as something that may appear as an auto-ethnographic recollection of events.

It behaves like a peeping hole into a very complex array of elements surrounding the rebuilding of national identities in the aftermath of conflict. Its use of recollection of witnessing through oral narration and diary reflections draws attention to the sensitive nature of the encounters throughout the trip. With the performative element of re-telling the story of the trip to a stranger, who illustrated my memories, I re-enacted what I had experienced. I turned myself into the storyteller/witness, who is passing-on the stories I had heard and situations I was confronted with. It presents itself as only a moment, rather than a monumental gesture, in order to portray the unstable, transient nature of unresolved ideologies which are in fact transglobal – those of an uncertainty which manifests itself as a fear of the past which has shackled the present and is threatening to grip on tightly to the future. It becomes an anchor point. This anchor, whether it is a witness corner or the actual space of a relevant event, speaks about the need for much more than a band aid solution but the consistent research, care, engagement and action that is being conducted by the many exceptional organisations and individuals working on the topic in the region.

August 2 – August 9, 2014

Ljubljana > Banja Luka > Sarajevo > Višegrad > Sarajevo > Banja Luka > Prijedor > Trnopolje > Omarska > Banja Luka > Beograd

2,040 km

Note to Reader – In many ways, I myself would describe my research as a form of commemoration – through the observation of destroyed memorials or sites where memorials cannot be built – as a somewhat idealistic infatuation with the possibility of finding a ‘cure’ for hatred.

On this trip I brought my cameraman, Miha, four cameras, and eight 60 minute HDV tapes. I planned the trip on a day-by-day schedule where I would meet survivors, artists, and activists. I prepared some simple questions:

i. What do memorials mean to you?

ii. Would you like to have a memorial?

iii. Do you believe a memorial helps with the reconciliation and alleviation of grief?

I imagined I was going to film a story about a ‘perfect’ memorial. I returned to Slovenia a week later with a couple of pictures of buildings on the Samsung phone I borrowed from my mother. I hadn’t managed any filming or photographic documentation. I hadn’t made any sound recordings or taken any written notes of the conversations I had.

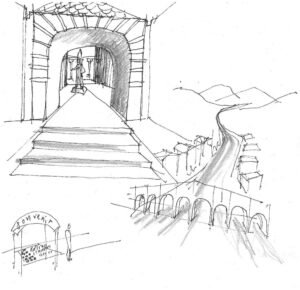

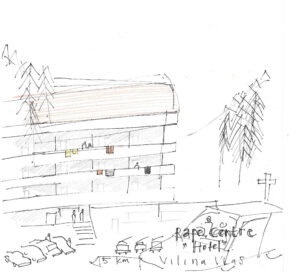

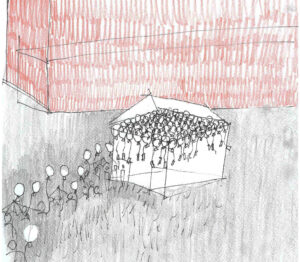

What follows are fragments of my trip as retold to the artist Vesta Kroese. Reverting to the forensic method of witness description composite drawings, Vesta tried to reimagine my experiences and draw according to my descriptions of spaces and situations. These drawings are the souvenirs of the trip.

Ljubljana > Banja Luka > Sarajevo

I woke up at 6.30 am yesterday with my mom ironing away next to the sofa where I was sleeping. My mom always wants me to be very prepared for every occasion no matter the situation. My dad was sitting next to me in his armchair smoking his pipe and waiting to see what my first words were going to be. My parents were both anxious and worried about my ‘first’ research trip. I was late to pick up my travel companion. Instead of leaving at 8 am we were off by 9. Despite the traffic we managed to get to Banja Luka quite quickly. Coming into the city, we were met by a family friend that took us to the local park for coffee and a quick chat. We sat down and quickly started discussing the trip, my reasons for it, and what I would be able to accomplish in one week in August, when most people were away on holiday. I asked my family friend a bit about what life was like now in Banja Luka, the capital of a region where some of the most horrible war crimes were committed during the Balkan war. He repeated a sentence that I had heard before and was to hear again that day. It was strange how quickly things changed. My friend went on to explain that before the war people did not think of each other in terms of nationality or religion. But now things are different. A terrible war that tore friends and families apart continues to linger. He explained that just a day before, two Muslim men had been shot in a café in Trnopolje, a town we were planning to visit. During the war, Trnopolje contained one of the most notorious concentration camps. In August 1992 reporters from ITN and The Guardian had filmed emaciated prisoners in the camp. The horrors of the war become front-page news. I knew this trip was going to be difficult, but I only then began to realise that it was likely that most people my age that I passed on the street or saw from the car had lived through the war and had their own distinct memories of it.

We drove from Banja Luka to Sarajevo. We were yet again greeted by another family friend. Again we sat down and had a brief chat about life in Sarajevo; what remained, what was rebuilt, and what was destroyed.

After settling into a hostel in Baščaršija, the city centre, we decided to take a walk and have a beer after a long day. It was almost 10 pm and the city centre was filling with the evening crowds. Music played from cafe terraces, people were drinking coffee and smoking shisha; it was difficult to imagine that twenty years ago this city had been near destruction. That day, someone explained to me that although time passes we must be careful to remember history because it tends to be easily contorted by a collective amnesia.

Sarajevo > Višegrad and Drina

Višegrad is one of the towns where most of the Bosnian Muslim population is now gone. As I later found out, it was also one of the cities where most of the executions and torture occurred in public spaces in order to intimidate people. Not many returned. As we drove into Višegrad we tried to find a parking spot where we could wait for Bakira. I made my way to what looked like the centre of the town. In fact, it was a newly built structure by filmmaker Emir Kusturica, known as Andrićgrad, named after Ivo Andrić, the author of The Bridge on the Drina. Kusturica has a reputation for being staunchly pro-Serbian. I remember some years ago, my father swore to never watch any of his films again. The glaring sun struck the whiteness of the newly built town, constructed as a set for Kusturica’s new film. A large parking lot dominated the area in front of the city gate. Just past it, a couple of steps lead under an arch and onto a white stone path with small houses on either side. Souvenir shops and restaurants lined the main street. The town opened the day before I arrived, and there were only a few local tourists taking pictures of the crisp, new, mini-town. It felt like a theme park. The restaurants were all open yet no one but the staff were in them. The town square, with its large monument to Andrić, was empty.

I travelled to Višegrad to meet Bakira, a woman who has been fighting for the rights of civilian victims of the war since it ended. She has been active in The Hague, creating an organisation to support female victims of war. Because of her work, rape has now become widely acknowledged as a war crime. I met with Bakira because I had read an article in The Guardian by Julian Borger. Julian wrote about Bakira’s struggle to protect a house where Bosnian Muslims were burned alive. The house still belongs to a woman that emigrated to the US. Since the war, the local government decided they wanted to tear down the property, removing any evidence of the fire. The owner of the house has given the right of attorney to Bakira and the Women Victims of War Association. Bakira has been able to find funds to fix the house. The upstairs has been transformed into an apartment for the owner, who might like to return someday, to die in her house. The lower ground floor, where the murders were committed, has remained intact.

I waited for Bakira in the parking lot of the new mini town. She arrived in a car with another woman in her early forties. They asked us to follow them, and we drove onto a nearby hill. Višegrad is built in a valley on the banks of the famous Drina River. The bridge across the Drina is infamous for being the site of many of the crimes committed during the war. We drove further up the hill and parked. Bakira stepped out of her car and shook my hand. She looked much like the photos I had found on Google but thinner (she mentioned she lost weight while building the house). Walking between houses on an unmarked path, overgrown with weeds, Bakira apologised for not having the keys to the house with her, but said we could look through the windows. The house was built on a slope with others in close proximity. The house had a new façade, appearing from a distance as if it were completely new and without a history. As we approached, the wooden foundations of the house could be seen charred and black. I peeked through the window and saw what I recognised from the photo in The Guardian article: a bare, cement column in the middle of the room, a burned floor, and not much else. It was a scorching hot day and Bakira led us into the shade. There were some bricks in the corner. She picked them up and started stacking them into three piles, making little stools. She offered us a seat, took out her cigarettes and started smoking. She smoked and looked around, then started talking; first about the house, what had happened, the people that had died in there, the babies that died in there, and about how they deserve the peace that at least they now have. It was difficult at first to follow what she was saying because she looked straight into my eyes. Her bright eyes looked so sad I lost my concentration. She explained that this was not a memorial but a room for memory; a room where the pictures of the people who died in there would be placed. A room that the family could visit, a place where people could visit and never forget what had happened. She was very firm about it not being a memorial. She believed in the idea of wanting the site of the crime to remain as is, untouched.

Bakira spoke very little about her own torture and loss during the war. I knew from what I had read that she had been raped and beaten. I spoke and asked very little. There were so many other things that Bakira said, some I didn’t understand very clearly, some I cannot clearly remember – it was mainly my impression of her that remained. We walked back to the car; she smiled and gave me a hug.

We come to feel that these stories of rape and murder, slaughter and torture are something commonplace. We start to think of it as something that just happens. It is only when you look at someone that has experienced it that the abstraction disappears and the reality of individual suffering makes itself manifests.

Bakira told us we should go and see Vilina Vlas, a hotel in the hills surrounding the town that had been used as a rape centre during the war and was now, once again, a hotel and rehabilitation centre. We drove up through the forested hills. Reaching the top of the hill, there stood the hotel, which seemed a lot larger than in the photos. It was shabby and grey, and parts of the building looked abandoned, but you could see that people were drying their colourful bathing towels on the rusting balconies. We didn’t even step out of the car. We just sat there for a couple of minutes, looking. I wouldn’t have even known what to ask anyone in the hotel. How do you ask at the reception desk whether this is the place where girls and women were tortured, raped and killed? We drove back down the hill and were stopped by an elderly lady. She asked if we could give her a lift to the foot of the hill because she was finding it difficult to walk in the heat. She asked if we were tourists staying at the hotel. I said we were just lost. She asked us to drop her off by the road where there was a group of people gathering, near a cemetery. She was going to a funeral.

Miha and I decided to stop to see the famous Drina bridge. What remained in my mind most, were the stories of people being thrown off it during the war. We parked right by the bridge where there was another shabby hotel and a café. Both were as run down as the previous one. The bridge was being renovated but you could walk over it. On it were strange little souvenir stalls selling small sculptures of the bridge, fridge magnets, paintings on wood and stones. We crossed the bridge and walked up a hill to a viewing point. You could see how isolated and vulnerable the town in between the hills was, divided by the river. We sat in the shade of the café before heading back. We were surrounded by people but with Bakira’s words still fresh, we remained quiet and left quickly. We arrived in Sarajevo to a cool grey rain.

Sarajevo

We sat in the hostel waiting for the rain to stop, and chatted with the staff. The tour guide for the hostel explained that the biggest attraction was the war. Taking tourists to see all the locations they had seen destroyed on the news: the library, the marketplace, the Holiday Inn.

After the rain stopped, Miha and I went to see two exhibitions in a local gallery; one a permanent exhibition about Srebrenica, and another a touring exhibition about the Siege of Sarajevo. There were tours every hour. Both exhibitions were mainly photographic, with large black and white prints hanging on the walls. The exhibition about Srebrenica included an extensive archive with four hours of material to go through. It was gruelling and confusing, with scans of letters between government officials and a lot of footage from the trials in The Hague.

The Siege of Sarajevo was a smaller exhibition; it described the destruction of the city, the misery of death, and finished with a video about the Miss Bosnia competition that had been held at the Holiday Inn during the war.

On our third day in Bosnia, we went to meet Aida at the Sarajevo Center for Contemporary Art (SCCA). We discussed one of their better-known projects about the anti-monument movement. Aida suggested what we should see in the city. She spoke about buildings that were once emblems of the nation and representations of nationhood. We spent the next few hours trying to locate several of the sites. We went to the newly renovated library, where two million books had been burned. It is now completely restored. We also went to look at the market where 68 people lost their lives in a mortar attack. The market was alive and busy even for a weekday. At the back of the market was a supermarket onto which the names of those who died were written. The exact point where the shell landed, creating a hole in the ground, had a large vitrine placed over it to protect it. I approached a couple of men sitting by the vitrine and asked them about it. They commented on how badly it was preserved. The glass vitrine had not been sealed properly and condensation and dirt gathered inside, so it was difficult to see anything. It looked like part of a construction site that had been forgotten about. We continued our war tourism: the former building of the Olympic Commission; the Museum of History; the National Museum; the oldest Jewish cemetery; the largest Muslim cemetery. From one site to the next we realised that most of these buildings had been completely forgotten about. We would ask for directions on the street but hardly anyone could point us in the right direction.

While looking for the National Museum we were told that it had closed due to lack of funding. We arrived at the site and found two monuments. Both were part of the project run by SCCA between 2004 and 2007 called ‘De/Construction of The Monument’. The first monument, titled Monument to the International Community, is a representation of a tinned beef can on top of a pedestal decorated with the colours of the EU flag. Sadly, or not, most of the gold and blue plastic had been torn off, uncovering the cement beneath. Much of the rest of the monument was covered with graffiti.

The other monument, by the artist Braco Dimitrijević, was a block of stone bearing the inscription: ‘Under this stone there is a monument to the victims of the War and the Cold War.’ Each of the four sides has the same inscription in a different language – Bosnian, French, German, English. Unlike the canned beef, Dimitrijević’s more visually subtle approach seemed to keep people from trashing it. It stood beside the Museum of History, which at first glance seemed closed as well. The façade was ruined, with chunks of concrete coming loose. Somewhat surprised, we noticed an advertisement for an exhibition, so we went up the stairs to have a look. It was open, so we bought tickets and went to see another temporary exhibition about the Siege of Sarajevo. The exhibition mainly included photographs taken by citizens, objects, homemade weapons, and even a recreation of a typical room during the war. In the middle of the space, a semi-circle of boards displayed a timeline and information about war criminals, their crimes, and sentences. There were images of the cells where the criminals are kept. Most of them were in what looked like apartments that included kitchens, lounges and private workshops.

As I was leaving, I was stopped by the woman who had sold me the ticket. She asked if something was wrong because I was leaving so soon, and explained that I was welcome to come back with the same ticket any time to see the exhibition and the rest of the museum. Later that day, we drove to the hills above the city. I could never have imagined how many cemeteries one could see. On that sunny day, the bright white stones shone from all sides. As we drove out of Sarajevo, we saw the famous Holiday Inn again and were told it no longer had the accreditation to remain part of the Holiday Inn chain, and had gone bankrupt. Restored to its fresh colours it looked exactly like the images I remembered from television.

Banja Luka > Prijedor > Kozarac > Trnopolje > Omarska

We drove towards Banja Luka, the capital of Republika Srpska, for the next five hours. We arrived around 10 pm and were welcomed with an incredible feast: mushroom soup with mushroom scones, and then a mushroom risotto and quite a bit of wine and rakija. The next morning, breakfast was waiting for us and we had a long chat with my father’s friends. We talked about my parents, shared a few laughs, and then they started to talk about their own experience of the war. They explained that their daughter had been away on a high school student exchange in the US when the war broke out and that she was unable to return. They didn’t see her again for over a decade. Meanwhile, the father was forced to go into battle, the son was sent into training, and the mother remained alone. After the war, they explained, there was nothing: no food and no electricity. It took a very long time for things to become normal again. The father was hesitant to speak about much of his time in the Serbian army. He just nodded and said that they were horrible times and horrible things happened there.

Later that day, we drove to the region of Prijedor. The area is best known for the concentration camps that were covered in the international news in the summer of 1992. In the village of Kozarac, we were to meet up with Satko, a survivor of one of the camps, in a café beside one of the rare memorials to Muslim victims. Coming into the village, the memorial was placed in the little central square, with parking spaces all around it. Obscuring the memorial were large expensive cars with foreign registration plates: Germany, Holland, UK, Austria, Sweden, Denmark, France and even some from the US. Satko had invited us to join a group of American students who had also come to the region for the two days of commemoration.

Driving through the village, all the houses were newly built, many were almost mansions, most with the blinds down and seemingly uninhabited. We were taken to a place called Kuća Mira, the Center for Peace. Inside the Center for Peace, we sat in a dining room surrounded by pictures of people who had lost their lives in the war. Satko gave a detailed historical account of how the region was systematically attacked, destroyed, and its citizens transported to the different concentration camps. Kozarac was completely burned to the ground, with only the rubble of the mosque untouched. It had been rebuilt by the families that used to live there, but who mostly live out of the country now and return only a couple of times a year.

We followed Satko to the first concentration camp, Trnopolje. It was on the side of the main road that led through the village. We parked in front of a former school, which had been part of the camp. A local man came towards us yelling and waving for us to go away. In the region of Prijedor, much like in Višegrad, there is a general public denial of the incidents of genocide that occurred. Satko encouraged us to ignore the man as he continued to explain what the camp looked like, where the barbed wire had been placed and what the conditions in the camp were like. Trnopolje was the camp where the infamous photographs of the emaciated prisoners behind barbed wire were taken. Satko explained that Fikret, the man in the main image that was plastered all over the news, was forced to hide after the pictures came out. He had dressed as a woman to avoid detection, defecating on himself so that he was pushed aside because he stank. Satko smiled and picked up his mobile trying to call Fikret; after a brief conversation he explained that unfortunately Fikret was away on holiday, so we wouldn’t have the chance to meet him. We stood in front of the empty building that the authorities had begun to renovate in spite of the efforts made for it to remain as it was. On the road in front of the building stood a memorial dedicated to the Serbian soldiers that died in the war. It was a stone eagle with its wings spread, built in a style similar to many 1950s memorials erected by Tito’s Yugoslavia to the heroes of the Second World War. At the foot of the monument lay flowers.

We woke up to another rainy day. It was 6 August and the only day of the year that people are allowed to visit the other concentration camp that lies only a few kilometres away from Trnopolje, in the village of Omarska. The Omarska concentration camp was known for being the more deadly of the two. A working iron mine before the war, it reopened quickly after the war ended. In 2004, ArcelorMittal Steel became the majority owner. While the new owners promised they would allow for a memorial to be built, so far they have only allowed part of the former camp to remain untouched in an otherwise operative iron mine.

Driving to the camp, we passed police, the army and private guards. We parked at the end of what was already a long continuous line of cars parked along the road. We walked down the muddy gravel road. Upon arrival, we heard that the commemoration ceremony was going to be cut short because of the rain, and soon after the national anthem and moment of silence, a male voice began reading out the names of those that perished in the camp. The camp was made up of two smaller buildings and a large red hangar. It looked exactly like the images and videos I had seen. I had read about the camp, and I knew that the smaller building, the White House, was where most of the murders were committed. Behind the White House, white balloons were being filled with helium. People stood next to each other, forming a long line behind the building, and passing the balloons one by one through an open window. It was raining heavily but people stood still, some in silence, some chatting and laughing, and some crying.

I made my way to the entrance of the White House. It was filled with people and camera crews. The back two rooms were filling up with the white balloons, hovering on the ceilings. Women were taking them from one room to another and reading out the names on the cards that dangled at the end of each string. It was a self-initiated intervention that they had been doing for a couple of years. In one of the front rooms an interview was taking place. In another, stood a man, his wife and two daughters. He had scars on his head. A lot of them. There were a couple of people standing around him and he was explaining how he was tortured. Suddenly, he ran towards the back of the room hitting the wall and collapsing to the ground crying. It was the first time in 22 years that he had visited the mine where he had been held captive. The house was filled with whispers and cries; loud enough to hear in snatches, and quiet enough to hear the constant weeping. I kept moving around, entering and leaving the house. It was almost noon, and time to leave the mine. Through a microphone, a voice asked everyone to take a balloon. A young woman approached me with a balloon. She gave it to me and nodded. I think I got number 436, but I cannot remember the name on it.

At exactly noon we were asked to release them. The wind and rain caused most of the balloons to be blown back onto the ground. People started running after them, encouraging the balloons back into the sky. I watched as an elderly woman kneeled in the grass, trying again and again to lift the balloons from the ground.

Belgrade > Ljubljana

I soon left Bosnia and made my way to Belgrade to meet up with members of the Four Faces of Omarska, a group of artists and thinkers that have been working with the topic of war crime denial and the possibilities of changing the methods of memorialisation. I met Srdjan, one of the members, for a beer to discuss their work and my own. We talked about how things are in Belgrade after the war and how difficult it is for them to work with their topic because the memories of war are completely different for most people. Here, the war meant isolation from the world and a once cosmopolitan city being left behind. On the long drive back to Slovenia I thought about everything I had seen, trying to replay things in my mind. There was so much I heard that I knew I could never talk about publicly. On the one hand, I do not want to put anyone into uncomfortable or potentially dangerous situations. On the other, many communicated what they had seen and done with solemn stares, their eyes speaking more than their words. I cannot translate those looks; those eyes worn with sadness. What I will remember most clearly is people repeating that before the war no one ever asked whether you were Bosnian, Serbian, Croatian or Slovenian. It didn’t matter then.

The first iteration of A week in August was designed and appeared in Death Part 1, published by Eros Press in 2014, and

edited by Sami Jalili.

¹ While monuments dedicated to women are a rare occurrence, in 2020, the same year of the inaugural unveiling of the monument dedicated to Wollstonecraft, the city of Budapest decided to begin a project which would result in the selection of a monument dedicated to women raped in times of war. The project includes a series of discussions, a website (https://www.elhallgatva.hu/tudastar/), a collection of personal memories passed down through generations, and a selection committee including two international experts from the field (Milica Tomić and James E. Young). This will be the first of its kind dedicated to highlighting the discussion of these violent acts. Bruder, P. (2020) Budapest to become the first European city to commemorate women raped in war times, Daily News Hungary, 20 November. Available at: dailynewshungary.com https://dailynewshungary.com/budapest-to-become-the-first-european-city-to-commemorate-women-raped-in-war-times/ (Accessed: 20 March 2023).

² BBC. (2016) Grim history of Bosnia’s ‘rape hotel’, BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-europe-35992642 (Accessed: 20 March 2023).