On Forest Walking and Ecologies of Care

The UNESCO protected Curonian Spit – a narrow strip of sand dunes separating the Curonian Lagoon from the Baltic Sea – has been shaped by centuries of drastic deforestation and the extensive afforestation of moving dunes, positioning the existence of a forest as central to the survival of human settlements. As a place with active geomorphological processes and a long history of cultural intervention in land and forests, the spit lacks a firm referent to the ‘natural conditions’, providing a perfect field laboratory of the naturecultural ecologies of the Anthropocene.

Thanks to the Neringa Forest Architecture residency, I spent three months in 2021 observing the local forest ecology. And yet, in this essay, I cannot contribute to the concerning topic of ‘Anthropocene ecologies’ directly from an academic or artistic perspective but only through its collision with an altogether other issue; the necessity of carework. This is because just when I got the chance to visit and research the Curonian Spit, I also had a small child to care for. Attending to the baby day and night, I could not imagine the duty of care and duty of expertise in anything other than conflictual terms. As each requires time, labour and focused attention, it is difficult to think of them together. However, as feminist theorist Nancy Fraser recently diagnosed: under capitalism, care and ecology have something in common – both of them are systematically undervalued and exploited. Just as the ecological crisis and crisis of care are entangled, the common sense of keeping them as separate is a part of the problem because we cannot adequately grasp one without considering the other.¹

The tension of trying to attend to the concerns which are kept separate and together exactly at the same time has situated my exploration of the Curonian Spit forests in an obscure field of the reproductive, productive and ecological. Counter to my academic training, which would expect me to focus on the most topical, urgent aspects of the forest problematics, I had to sidestep the logic of professionalism to explore what it is that I could do in my situation significantly shaped by the necessity of child care. In this training of the imagination, it was important for me to find not what I can do despite the baby but precisely what I can do with one. Within my own set of possibilities, I identified one activity that keeps childcare and the forest in proximity – daily walking. Reframing my daily walks with a child from the act of care to the act of care and (knowledge) production, I walked daily with my small companion for three months, experiencing subzero temperatures, melting snow, emerging flowers and finally sprouting trees.

Walking as a method out of a necessity

Although walking has been part of the environmentalist canon since the romantics and naturalists, claiming it as methodology is not an unproblematic choice. The excursive walking performed for informing and shaping knowledge has emerged from troubling histories of race, class, gender and able-bodied privilege normalised through charismatic figures such as the American naturalist Henry David Thoreau. His influential writings on life in the woods – still printed and sold in the twenty-first century – delineated walking as a highly individualistic act that privileged a distanced observation over other eco-social relations.²

Mending such celebratory views, geographer Kathryn Yusoff situates walking as a corollary to the dual experience of colonialism. As she aptly remarked, walking pertains to both ‘the lone white subject of Western Modernity surveying His landscape as possession and diasporic subjects walking their displacement and dispossession.’³ Walking as a method means navigating the line between those who are free to walk and gaze for their enjoyment and those who walk as an act of necessity and survival.

To be clear, carrying a baby does not absolve the weight of privilege nor guarantee mindful sensibilities. But still, my walks were less of a choice and more of a method of necessity as they provided practical means for an essential effort of keeping the carework and academic production in relation and not in dichotomy. I had no clear idea whether I could achieve something of relevance. However, there was a pleasant certainty in the unhurried daily routine, movement and fresh air. Also, when possible, I walked with other people and listened to their forest encounters and relayed experiences of others. So, I spent hours in the pleasant company of a baby and sometimes also other forest-concerned people. My way of walking allowed me to encounter the forest not as a space of solitude but as a space of sociality and social reproduction.

Forest heterogeneity

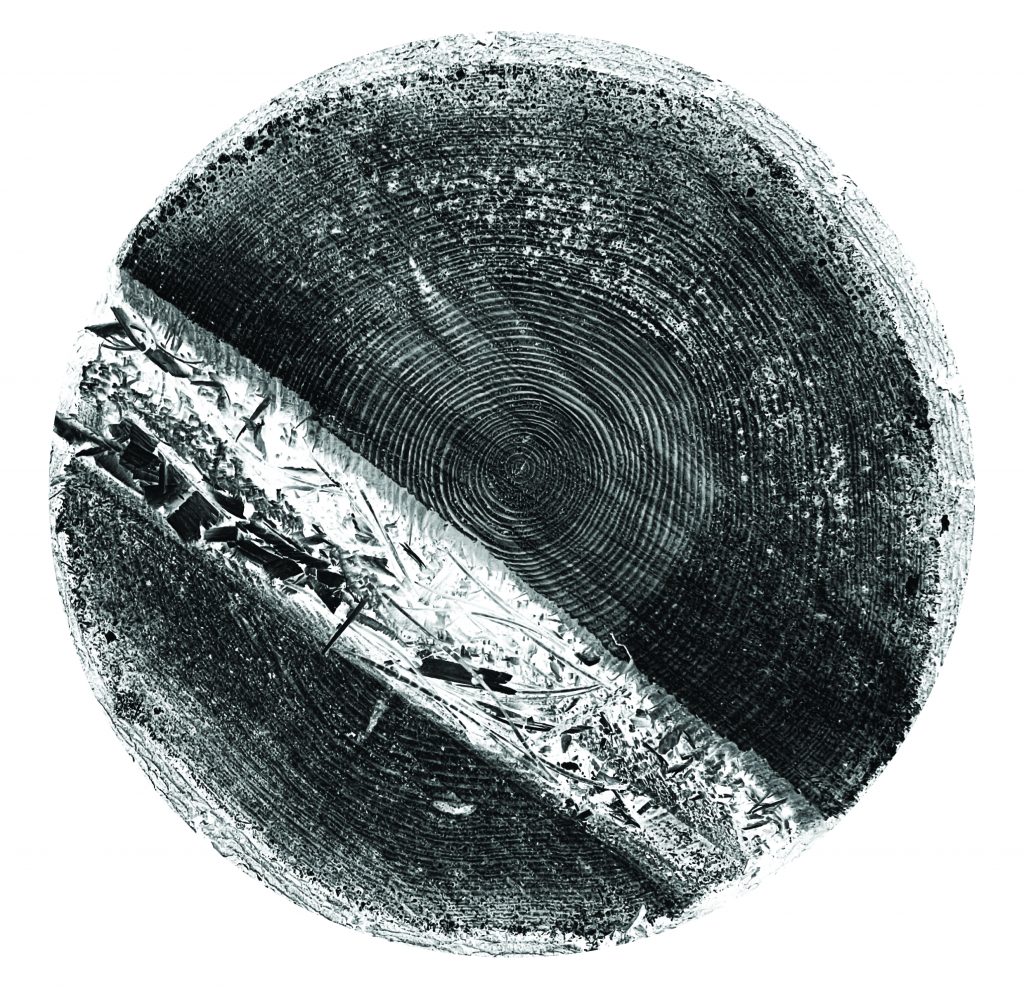

Within the very first days of walking the landscape around the residency its variations were highlighted to me. Although I restricted my walks to a circle of one kilometre, rather than one forest, I encountered a heterogeneous assemblage of forest habitats of different ages, planting design and species compositions. The steep slopes of an old dune covered with the old-growth stands of Scots pine (Pinus silvestris) forest coexisted alongside more recently planted plots of Scots pines of different ages and densities. In some places, the pine stands alternated with spruces and mixed forest. Higher and more exposed parts of the dunes were covered with expansive, dense stretches of mountain pines (Pinus mugo), originally brought from Denmark. This foreign species, which can root in poor, sandy soils, quickly spread out through massive reforestation activities at the end of the nineteenth century. Involving hundreds of (mostly female) workers, the afforestation aimed to stabilise the dunes in order to save local villages and regionally-important land and water trade routes from wind-blown sand, which was put to motion by earlier forest damage. The interdune depressions and wet planes have been covered with a mix of broadleaf trees, mainly black alders (Alnus glutinosa). Most of the trees were planted with the same intention – to prevent sand erosion and promote the development of soils. But even in this highly intentional landscape, forest managers were faced with fighting unwelcome aliens, such as Robinia pseudoacacia and rapidly-spreading beach rose shrubs (Rosa rugosa). And more. Once an essential landscape element, the hundredyear old and increasingly dry mountain pines were in recent decades burnt by massive fires or preventively cut down, leaving behind jarring clear-cuts to be replanted. The new soil broadly allowed for the reintroduction of ‘native’ Scots pines but still in some places the mountain pine seedlings returned. No longer needed for utilitarian purposes, now they were retained for the preservation of a ‘characteristic landscape’ aesthetic. And still, places where the forest workers were slow to arrive were quickly colonised with dense concentrations of young birches, a typical pioneer tree species, manifesting the gap between forest management plan instructions and the age-old processes of ecological succession.

A planted forest as a space of ecological relations

My daily walks made me appreciate that the forest is changeable, historical and plural. However, that the Curonian Spit forests are heterogeneous and shaped by a varied planting history can also be inferred from historical maps and satellite imagery. Did my walking lead to any insights which could not be accessed through the more conventional research approaches?

In retrospect, I realised that in contrast to the static cartographic imagery, the daily routine of physical walking had accentuated the forest as a space of a multitude of material relations of trees with other lively beings. Instead of the atomised description of the forest as a sum of different and disconnected parts, I experienced a sense of interrelation.

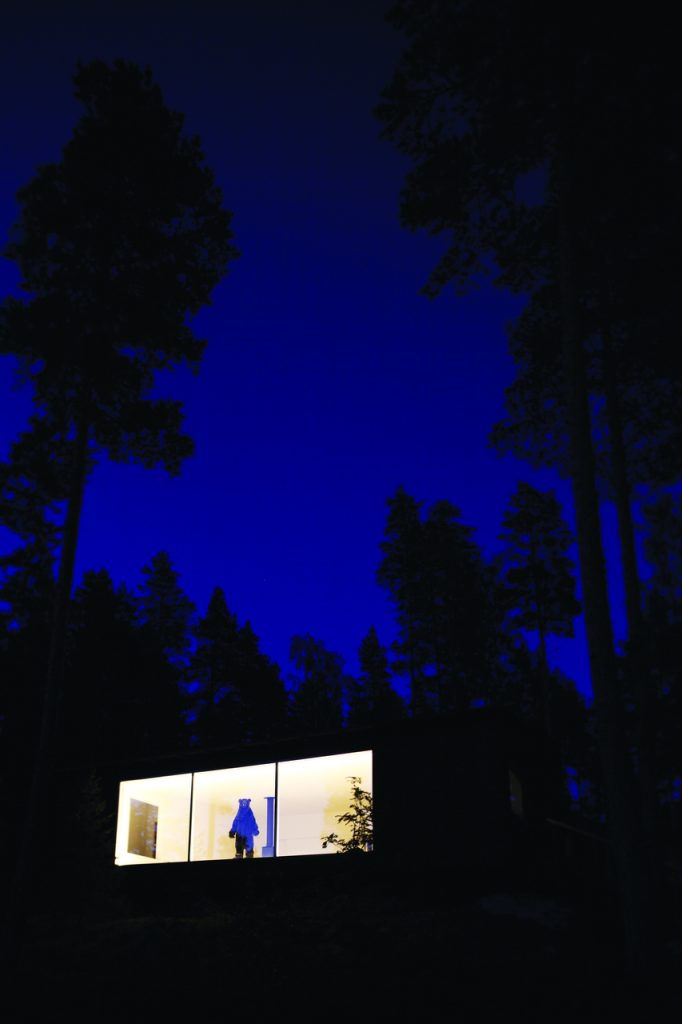

Even the monotonous, geometrically organised stands of impoverished Pinus sylvestris monocultures, planted with the sole intention to prevent the movement of sands, have become something else: at once a soil generating technology; but also a habitat of proliferating wood-grown fungi and lichen, home to large flocks of greenfinches, common chaffinches and goldcrests; a habitat for deer and foxes; and, at the same time a biophysical testament to the utilitarian approach to nature, generative of uncanny and haunting sensations. Elsewhere, the monocultures of imported mountain pines (Pinus mugo), which could best be described as relics of another era – once useful in supporting the whole spit’s existence but now without any recognised ecological value – presented their drying trunks and extremely dense layers of branches, overgrown by thick layers of lichen, as a new form of wildness. Established through human labour, the thick stands of mountain pines became impenetrable to the human body or gaze. And while they do not offer species diversity nor sense of beauty or sanctity, they generate a sense of quiet otherness – of someone living in close proximity yet unfitting the prevailing aesthetic and value categories. Often described as ‘low biodiversity’ or ‘poor quality’ forests, I found these places to matter not because of nostalgia for the quaint sceneries but because of their unobtrusive but generative vitality, which extended beyond the intentional and descriptive.

Rather than engendering a definite knowledge, my walking encounters have allowed me to experience the forest not as a place composed of trees but of material relations that have proliferated when the trees were left to grow, opening up new questions: how to attune to the lively exuberance of any forest without nurturing a false sense of equivalence among different ecological assemblages? And, how to appreciate what is already there without precluding the possibility of more biodiverse and abundant ecologies?

Imagining more caring forest scenarios with the mountain pines

But how to recognise ecological dimensions of places that do not fit the very categories of ecological science? Drawing on queer and trans theories and their attention to the constitutive yet unacknowledged role of otherness in constructing (often binary) master narratives, geographer Matthew Gandy proposes a queer ecology as a corrective to the participation of ecological scholarship in the normative and reductive framing of the natural. For example, his queering of urban ecology foregrounds the unacknowledged complexity of marginal and interstitial spaces and highlights links between their invisibility to environmental science and the broader societal ‘aversions’ to the aliens.⁴ The emergent notion of queer ecology clearly means more than acknowledging that which unsettles established categories and taxonomies. Notably, against the simplified recasting of the nature-culture binary as a smooth continuum, the queering of ecology exposes how these entangled realms are connected through the situated processes of othering and exploitation – thus potentially finding starting points for conceptualising ecologies more attentive to difference.⁵

What could queer ecology mean in the context of the unnatural forests of the Curonian Spit? Let’s consider the unfitting if not controversial figure of the mountain pines. Although most of the local forest is to a different degree constructed, the mountain pine stands out for its paradoxical position: the tree, which once helped to stabilise the moving sands and preserve ecological and human communities, has been nowadays devalued in multiple ways simultaneously. The species is considered not native, not very beautiful, its habitats are of low biodiversity, and the wood is not of good quality. These categorical descriptions are not untrue, but they make the ecological relations and otherworldly presence of the mountain pines invisible and unaccountable. What is more, their scientific evaluation is not in contradiction with the extractivist forms of their management through large-scale clear-cuts and massive tree removals.

Making space for the mountain pines in the local ecology would require a critical imagination of different concepts and practices that could account not for what the mountain pines are not (categorically beautiful, biodiverse, native) but for what they are – artificial relics prone to burn yet still lively beings supportive of ecological relations. Focusing on the double characteristic does not simply highlight the ‘queerness’ of these botanical aliens; instead, it invites exploring processes of devaluation: how did something useful and cultivated transform into being overtly dry and dangerous to other communities? The extremely high density and dryness of these habitats is nowadays treated as a natural, inevitable feature of these aliens. However, in fact, it is a product of human neglect. Once densely planted, the mountain pines were left to overgrow and age without any care.

Exploring the ecological position of mountain pines reveals a complicated interplay of the categories of natural and cultural – especially, how carework seems unfitting – in our definitions of a forest, which seem to be polarised between not needing any care intervention (in the case of ‘pristine’ or ‘natural’ forests) or not deserving of care (planted monocultures or non-native species). Looking speculatively at the history of the Curonian Spit through the notion of forest care, suddenly it seems that the artificiality of the mountain pines did not have to predetermine them to the fate of complete obliteration through massive extraction, as the only possible scenario. Critically, proposing the care intervention instead of clear-cuts does not imply that the mountain pines must be conserved and endlessly replanted. The situated notion of ecological care could mean investing in the activities preventive of neglect and the accumulation of unnecessary hazards. And, it could also mean letting the mountain pines be replaced by other species in the cycle of ecological succession.

Incidentally, my project started with the notion of care. Admittedly, for much of my exploration, my consideration of carework remained strictly confined to the world of human relations or perhaps even oppositional to the realm of forest ecology. Walking in the mountain pines and experiencing the gap between their aesthetic otherness, past importance and current ecological non-value highlighted to me that precisely the notion of forest or ecological care could be the analytics needed for queering the polarity of cultural framings of forest as a space of either static preservation or clear-cut extraction.

Recognising the ecological interrelatedness is not merely about celebrating that everything is connected but about discerning that the naturecultural entanglements are not immutable and could be different. Accepting the unnatural forest as a space of ecological relations and also as a space that may need care, through practices that support what is there, could open up possibilities to shape more diverse and abundant forest ecologies – provided that the cultural forest practices are treated as a terrain of possibility for ecopolitical transformation away from devaluing practices of extractivism to eco-social relations of care.

Agata Marzecova, a Tallinn-based researcher with a dual background in ecology and photography & new media. In her environmental research, she investigates changes to the ecosystems of small lakes and their catchments during the transition from Holocene to Anthropocene. In recent years, she has been working on art-led collaborative projects, which explore the porous boundaries between science, technology, aesthetics and environmental politics. In 2021, Agata was a resident of the Neringa Forest Architecture programme at Nida Art Colony (NAC) of Vilnius Academy of Arts.

- Nancy Fraser, ‘Climates of Capital’, New Left Review 127, January–February 2021, pp.94–127.

- Henry David Thoreau, ‘Walking’, The Atlantic Monthly, A Magazine of Literature, Art, and Politics, IX (LVI), June 1862, Ticknor and Fields, Boston, pp.657–674.

- Kathryn Yussoff in Stephanie Springgay and Sarah E. Truman (eds.), Walking Methodologies in a More-than-Human World: WalkingLab, Routledge, London, 2017, p. xi

- Matthew Gandy, ‘Queering the Transect’ in Matthew Gandy and Sandra Jasper (eds.), The Botanical City, Jovis Verlag GmbH, Berlin, 2020, pp.161–169.

- For example, see Greta Gaard, ‘Toward a Queer Ecofeminism’ in Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy 12(1), 1997, pp. 114–37; Darren Patrick, ‘Queering the urban forest: Invasions, mutualisms, and eco-political creativity with the tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima)’ in Urban forests, trees, and greenspace, Routledge, 2014, pp. 209–224.