Reverse Memory Engineering by Michael Shubitz

It’s our first online meeting, and Michael Shubitz has already given me a tour of the apartment he stays in when in Germany. He is a fantastic interviewee because he is full of stories and references. The curator of this issue, Daiva Price, first introduced us in order to talk more about his photography project ‘Back to Kaunas’.

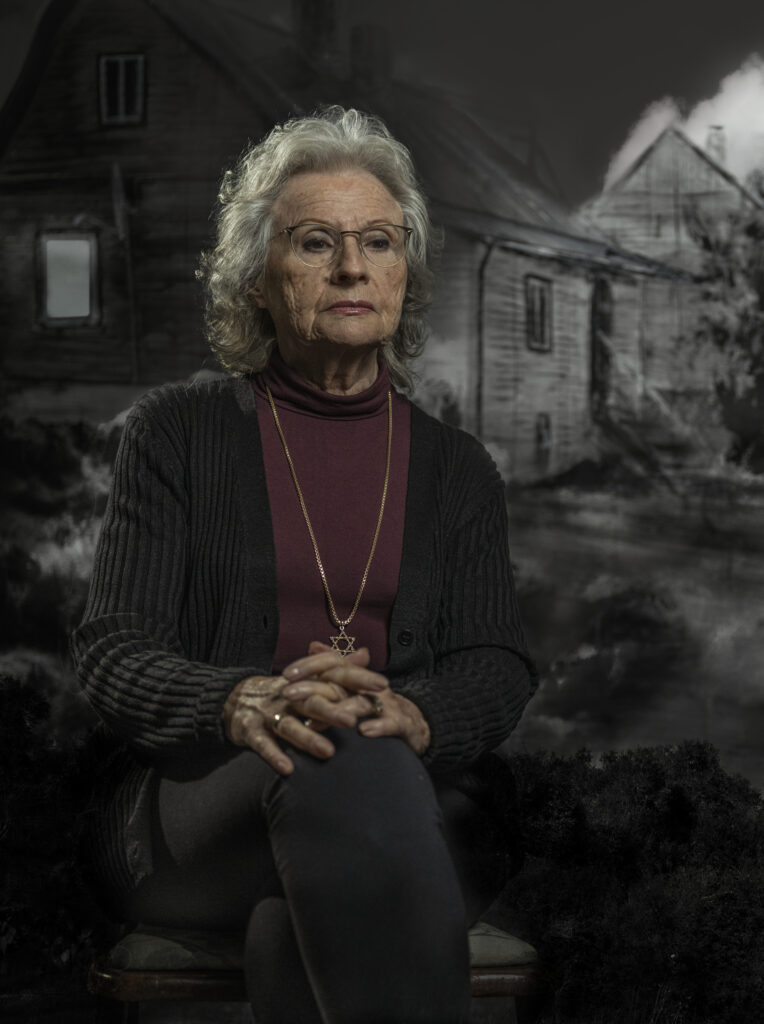

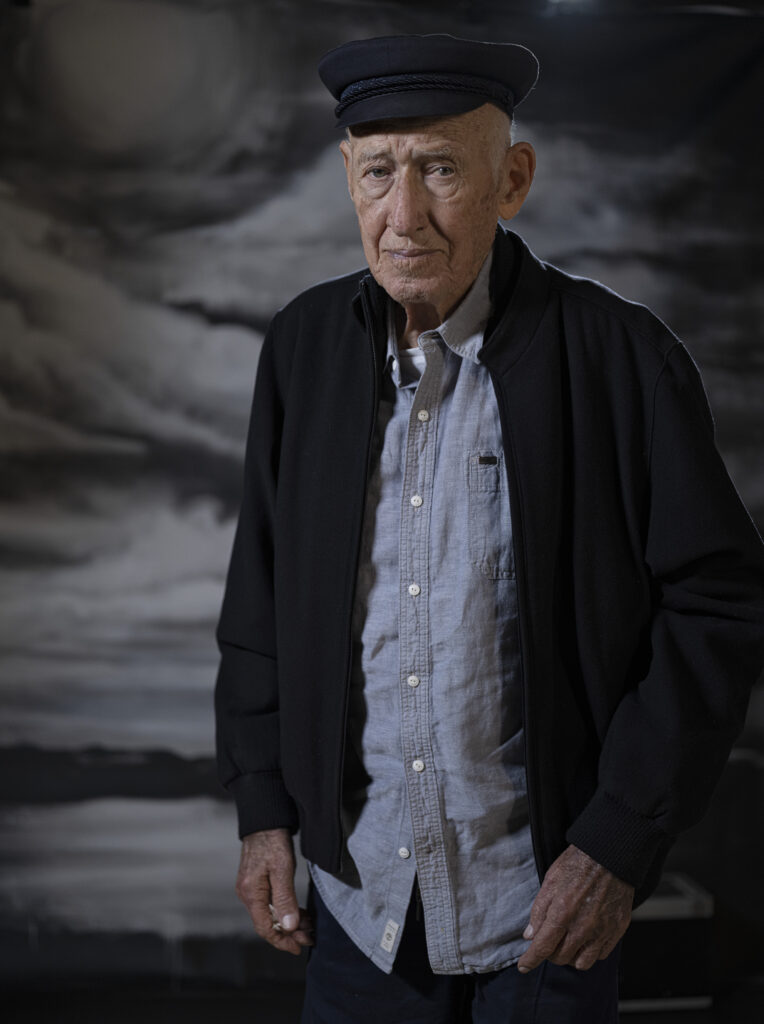

As a cameraperson for German television broadcasters ARD and Bayerischer Rundfunk, based in Israel, the project presented a new challenge for Shubitz: to pause the movement and create still images. In ‘Back to Kaunas’, the artist features survivors of the Kaunas Ghetto and their corresponding stories. An exhibition of the photographs first opened in Kaunas in September 2022 as part of the Litvak Forum organised by the European Capital of Culture. It subsequently toured to Ukmergė before arriving at the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum in Vilnius (June 2023).

Behind this photography project (and a new one in the making) lies the story of Michael’s own family – one that is still being written decades after the events happened.

Kotryna Lingienė: I understand that your parents did not speak about the Holocaust. Did they speak of their life in Lithuania at all? What was your childhood like?

Michael Shubitz: I was born on the street that runs parallel to the beach in Tel Aviv ten years after the second world war. From my balcony, you could see the beach, you could smell the beach, and my childhood was dominated by a kind of Mediterranean lifestyle – swimming, fishing, sailing, and whatever else the sea offered. From around the age of ten, I was almost never at home because I was enjoying that lifestyle.

While I knew that my parents were from Lithuania, aside from that, I knew very little about their lives there. Relatively early on, however, I realised that my house was different from my social environment. In Israel, you have people from many different countries. My parents, like other people who came from a region once part of the Lithuanian Grand Duchy, talked Yiddish among themselves. I, on the other hand, spoke Hebrew. I cursed in Arabic. I listened to different music to my parents. When I was six, The Beatles came along, and my parents didn’t like this at all. They loved jazz, tango, and classical music. When I was a teenager, these differences led to conflict because I would criticise them. I would say, ‘Listen, you are from another country. You’re the diaspora.’

Nevertheless, they were good parents. We were a happy family. Israel was very simple at that time. It was a poor country, a new country. I had a simple childhood, and many simple things made me happy.

Only later in my life did I find a way back to them, but they were not there anymore. They passed away very young. While I was no different to any other teenager with a disinterest in making a connection with their parents, one might say I was stupid, or maybe I was just empty. It was only later that the empty box started to fill itself with things from the inside.

As an adolescent growing up at that time in Israel, the Holocaust was ever present from early childhood. You heard all the terrible stories. I remember thinking that if my parents weren’t telling those stories – it must not have been so terrible for them.

My father passed away when I was 18. It was just as I had begun to show an interest in our family history, but he would not reveal anything. Others of that generation couldn’t stop talking about what had happened to their families, but my parents were completely silent.

KL: I first heard your story during the Litvak forum in Kaunas in September 2022. What caught my attention was the traumatic experience you recounted of seeing the bodies of victims of a suicide bomber at close range, which subsequently led those treating you for this trauma to ask: ‘What happened to your family during the Holocaust?’ You replied that you didn’t know, and that prompted the beginning of both an artistic and physical journey to Lithuania. Is that an accurate summary?

MS: Almost, almost. By accident, I was at the scene in a market in Tel Aviv right after the bombing, and nobody stopped me. It was a Friday, and I could drive through a closed market that is usually a pedestrian walkway. The victims were lying around dead. The amount of blood, the screaming of the shocked and wounded, the body parts lying around, the smell of burnt flesh, the sound of the streaming blood… Usually, when you come to sceneries like this, you are blocked by the police. There is a designated place where they let the press stay to take pictures, but you don’t usually see much.

It happened during a very hard period for my wife, as her sister had died. I just kept on working, I had a lot of work, really, and I was not aware something was wrong with me. It was business as usual. My wife was talking to a friend of mine, assuming that I was asleep, but I wasn’t. She said, ‘Listen, you have to take him. He’s not okay.’ When she said, ‘He’s not okay,’ it hit me like a flash, ‘She’s right. I’m not okay. I’m somebody else in my body.’

I stood up, and I didn’t say a word. I left the flat half asleep and went to the emergency room. I said, ‘Listen, when people come from a suicide bombing with a shock, where do they go?’, ‘Go two floors down.’ they said. I went down and said, ‘I need help. This and this happened to me, and I’m not okay.’ A psychologist came and said: ‘OK, come tomorrow.’ I started the treatment, first daily, then weekly. Then life went on, but it helped me a lot.

Quite soon after treatment started, the psychologist and I stumbled upon the fact that I didn’t know anything about my parents and that I wanted to know, but wasn’t doing anything about it.

She said to me, ‘You should do it now because it’ll haunt you later.’ that’s where my story with the memory of the Holocaust begins. Moreover, we very soon came to the notion that I am not a cameraman because of a chance but because of the position of looking at the world through a hole – that I am doing this dirty job as a part of a much bigger event in my life. It was the summer of 2001.

KL: Your photographs are rather cinematic, including the backgrounds, which is no surprise knowing that you also shoot film and video. So, let’s go back a little bit. When did you start your career as a cinematographer?

MS: I went to university in Tel Aviv right after my military service. Military service wasn’t an easy experience for me. I was eighteen, very rebellious and did not want to join the army, but I had to. It was August 1973, just a few weeks after my father passed away. On 6 October, the Yom Kippur War started right in front of my eyes in the Golan Heights. It was a surprise to us. The Syrian army began attacking us, and very soon, they were trying to get to the base we were guarding.

I was a new soldier in the army. It was my luck and my misfortune. I was on the border, and I had to shoot. I had to kill people because it was them or me. It’s a complicated story, but as new soldiers, we went to guard anti-aircraft rockets which we didn’t know how to use because we weren’t being trained in their use until later in the year. But, because it was Yom Kippur, so many people that were serving there, the regulars, had gone home, and we, the rookies, were sent there to fight a war nobody had bothered to tell us about.

Anyway, we all survived. I survived, and I was not traumatised because I already understood that the world was like this. That the world is shit, there are wars, and people kill each other. This was given to me with mother’s milk. It’s part of living in Israel. Many people I know carry heavy traumas, but I was swallowing it. I was sent to a kibbutz and had the chance to begin a new and quiet period in the countryside.

Then I decided that I wanted to study cinema. I loved the movies, and I decided I wanted to make them but it was only after I started studying that I realised I was attracted to camera work and was better at that than at telling stories with words.

During my first year in school, I was asked by one of my teachers if I wanted to work a few days with him in the desert for the German television broadcaster ARD. That’s how I made my first contacts and started working for them, initially as an assistant while still studying.

A good friend of mine was a director, and we worked together, but then he became Orthodox. It was a wide phenomenon at that time and is still happening today – people suddenly turn to religion, abandon their previous life and start a new one. That’s what happened with him, and I was left alone with my camera work. This led me to Germany, where I already had acquaintances from the desert project. I still work with them today, and we are friends. From 1982 to 1990, I lived in Germany, I got married, and my first daughter was born there.

KL: Did you decide straight away, back then in 2001, that photography would be part of your journey?

MS: No, that happened later. First of all, I needed the facts, I needed the story, and I came across a few junctions in this story that opened my eyes.

As part of my research, I went to the website of the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Yad Vashem, and entered ‘Giedraičiai’ in the search box. I knew the name of the town because, in the 1980s, my mother had an aneurysm and underwent an operation. After she woke up, she only spoke Lithuanian, which my sister and I could not understand. After a few months, she recovered – she didn’t lose her memory, but she needed speech therapy. So, one day, I asked her to tell me what happened during the Holocaust. I taped it (I still have the tape). She mentioned ‘Giedraičiai’ and I know of it also because my nephew interviewed my mother for school just before her stroke. So, on the Yad Vashem website, I came upon a testimony of someone who experienced the massacre in Giedraičiai. When the war broke out, my mother’s family tried to escape to the East, but the border was blocked, so they went back to their home in Kaunas, and found that the neighbours had occupied it. They threatened my mother’s family, who then went to Giedraičiai, because that was where my grandfather was born. In the testimony I found online, a person had written about my grandfather, including dates, names, who killed him, how he was killed along with 27 others.

This man, Israel Katz, recorded everything in real-time. He was walking around with a small book. Can you imagine? Walking through such atrocities and writing down names, who did what, where people were buried, who raped who. He understood that he was experiencing something so exceptional that he decided to write it down. This testimony is one of the most shocking stories I have read about the Holocaust because it’s so real.

I’m in good contact with Katz’s family. We have already met in Tel Aviv, and we plan on making a film together. His daughter is still alive; she is 96 years old.

With Katz’s help, I was able to find out not only how my grandfather was killed but also what my mother saw. She had told me things that weren’t in Katz’s document, but I put all the stories together. And, as I am a photographer, I am always thinking in images and shots. During the Lebanon War in 1982, I worked as a still photographer for the Israeli government. I am very interested in freezing the moment.

KL: In your project, you present twelve people born in Kaunas who spent their childhoods in the city and saw their family members murdered. Did they easily agree to be the subjects of these photographs? How did you meet them?

MS: Some of them I knew, some of them I didn’t. Nobody very close – mostly, they were relatives of someone I knew.

Actually, there was one guy I have known for many years, and he didn’t really want to cooperate with me on this, because of our long history together. But he was from Kaunas, so we worked it out. I met him in Germany recently. Coincidentally, I managed to convince the vice chairman of the Bavarian Parliament to show my exhibition there next year. I hope all of the participants will be able to witness it. I also want to make a trip to Kaunas with three of the protagonists and make a film there.

Can I ask you something, Kotryna? What do you think about the pictures?

KL: I like them. In fact, I would like to meet all those people – their portraits look welcoming. I was not really surprised to learn later that you are a cinematographer – but hey, we have already covered this. But yes, when I looked at the portraits for the first time, I thought they could be stills from documentaries about these people. They’re also very different from one another, and that’s what I love. I love the differences of the expressions and their eyes. They are a very interesting set of subjects. They’re all very different, and they all come from Kaunas, which kind of highlights how multicultural the city once was. I wondered what would have happened to them if they still lived in Kaunas? Maybe some of them would have been my neighbours?

MS: Thank you. You made my day.

KL: OK, I also have a personal question. How do you feel about me feeling guilty when listening to you? I usually have this feeling when I’m talking to people that are family members of Holocaust survivors or family of those who did not survive the Holocaust. I have nothing to do with it, but I can’t escape it.

MS: I understand that. Jews, in general, if you can generalise things like that, also feel guilty about nothing – this is a Jewish joke of sorts. I can follow your feeling. I also feel very uncomfortable with what’s happening in the Palestinian areas because, as a cameraman, and a journalist, I saw a lot of bad things being made in my name.

I feel very guilty because I have quite a few Palestinian friends who are telling me what’s happening to them, and there’s nothing that I can do to change it. This is more understandable guilt. In your case, you are part of a process that we both are in, a process of finding, again, a way to each other. My family lived in Lithuania for hundreds of years, and then they were robbed, raped and murdered. My parents came to Israel with only the clothes they were wearing. That’s it. I’d love to get back what was once my family’s, but this will not happen. But I, like you presumably, want to make this world a better place.

KL: Did making this portrait exhibition make you feel better?

MS: The accident was 21 years ago, and it was not an illness. I was under pressure, having a burnout, but I’m carrying a trauma that is not mine; nevertheless, it hurts me very much. It’s unhealable because it’s not my trauma. Do you understand the difference?

KL: Yes. It means that you have to learn to live with it.

MS: Exactly. It’s actually a trip into the inner self, to knowing who I am, to understand many events in my life, why I did what and under a different light, through a different filter. It’s ongoing, and it will never end. I am not suffering from it, but the people around me are, sometimes.

Seven years ago, I worked on a pilot episode of a documentary about a Palestinian boy who grew up without a hand. He didn’t lose it in any fighting or in an atrocity. He was born this way, but his family is the only one who lives in an area that is controlled by settlers, and they’re having all kinds of problems and troubles. My producer asked the boy, ‘Tell me, don’t you want to have a hand?’ He replied, ‘Listen, I would like to have a hand, but we are very poor people, and I will not get it. Let’s talk about something else.’ After it was broadcast in Germany, we got 150 emails from people who wanted to donate this boy a hand.

When things like that happen, I see my work as being fulfilled. With this exhibition, my secret wish was that people would come to me and say, ‘The pictures are very good, very strong. They are telling a story.’ Instead, people talk to me about a healing process. Do you understand what I mean? For me, it’s a failure, but it’s still part of my artistic journey.

KL: What motivated you to create the portraits?

MS: In the beginning, Daiva, who as the organiser of the forum invited me, and I talked about me taking portraits of people who were born in Kaunas. Maybe also second generation, third generation – this was her wish. I said to myself, ‘What I really want to do is follow in the steps of my father and meet the people who were in the ghetto, like he was.’ Because, as I told you, he spoke very little of his experience. I could sum everything up he told me in five sentences. I told Daiva, ‘It will be survivors of the Kaunas Ghetto.’ She agreed. And thus it became my personal trip, too.

When I met Dita Zupovich-Sperling, to photograph her portrait and also make a film, I discovered the story of my father’s first wife. Dita had met the woman my father had lost. He actually lost her before she was killed, because became mentally unwell. So Dita, who is 101 years old and remembers everything, is just one example of how this process has helped me discover my own roots.

KL: This project sounds a little bit like reversed dementia. Instead of forgetting things about yourself, you are unforgetting them.

MS: Exactly. One could also call this reverse engineering – like when a US aircraft falls into Russian hands, they try to understand how it was made. I like this concept a lot, actually, my new project is called exactly that – ‘Reverse Photographing’.

A very disturbing factor that accompanied my research was that I had no photos (except one made in Vilkaviškis before the war) to support my imagination and understanding. Everything was burned, left behind, gone with the wind. In this new project, I intend to realise my research in photos. I will create the photos and rebuild the pictorial history of my family. It will consist of a combination of different layers and technologies that together will assemble the missing images. I intend to go to Lithuania and photograph the original places, the cities and villages, streets and houses where my family lived. I will use digital technology and Artificial Intelligence to create photos from daily life scenes, like the birth of a child, weddings, and street life to extreme Holocaust-oriented events like the daily life of the ghetto to deportation and execution where I know that my parents were.

KL: Last question. When you came to Lithuania for the first time, what impression did you have of us understanding, or rather trying to understand, the past?

MS: When Daiva spoke to me about this issue of ‘as a journal’, she described memory as a battlefield. I would like to suggest instead that the collision of the narratives is the real battlefield. The difference in memories of the same event is, so to say, a conflict.

History is always written in at least two versions. Lithuanians talk about Soviet trauma yet call the Shoah ‘Nazi occupation’. In my narrative, it is quite the opposite, since the Soviets saved the rest of the Jews. They also punished a few of the perpetrators, including the murderers of my grandfather. I consider myself to be Lithuanian, just as you are, only my family was kicked out of the country. I am sure, as a Lithuanian, that the Nazi occupation was the worst and darkest period in Lithuanian history. Other Lithuanians are certain that it was a good period, and some perpetrators are still honoured officially because they were anti Soviet, regardless of the fact that their hands were washed with Jewish blood, Lithuanian Jewish blood. It is my blood and my memory. My mother saw her father dragged out of their home, and when I was born, this memory was inside me. I should not have known it, but I cannot escape it. This is what is so strong about memory. It is in our cells.

When the memory is traumatic, one should look the trauma in the face. Again, the guarantee of identity and survival is the narrative. What to do when the memory is hidden, like in my case? Well, take the mask off, but don’t fall into hatred. Hatred is a poison that will poison the hater themself. Yet, it is the memory that we have to preserve to make a better world. How naive we are! Just look the truth in the eyes and don’t call it a ‘complex history’ because Jew-hatred is not complex at all. Xenophobia is straightforward energy.

One of the ways to make the world better is through education, and nothing touches people’s hearts more effectively than art. No one is born with hatred towards others because of their skin colour, religion or sexual identity. It is the education, the narrative that causes it. If so, it is also possible to counter those narratives by educating people to love, appreciate and respect each other, and that is what art can do.

I saw, during my visit to Lithuania, many young people who want to learn and understand. They wanted to listen. I have stayed in contact with some of them. I am committed to building that bridge even if the water underneath is troubled.