Illuminating Oneself by the Immense

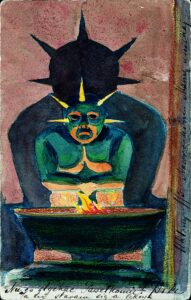

M. K. Čiurlionis, Eastern God, 1903. Postcard to the artist’s brother Povilas Čiurlionis, tempera, pastel, ink on paper

‘M’illumino

d’immenso’

‘I illuminate, clarify, and burn myself out from, in and by the immense’1

Immense. Much of M. K. ’ painting can be seen, and his music heard, in and through this famous poem by Ungaretti.2 The described or hinted act of the poem has three components: the implied ‘I’, the action of illuminating, and the immense. Although the action is expressed by a verb in the active voice, its source and indirect object is the immense. But since it is immense, it cannot be named, so ‘immense’ inevitably – and maybe intentionally – misses the point. It is a designation of privation: immeasurable, that which has no measure, at least a measure established by us. Still, in self-illuminating I hope (the ‘I’ hopes) to measure – illuminate – myself from this immeasurable.

Having no measure that can be established, the immense is the actually infinite, because the potentially infinite always has a measure by which it can be extended or divided ever further. But the actual infinity is undivided and whole. Paraphrasing Aristotle, for whom the (potentially) infinite is that outside of which one can always take something (Physics 207a1-2), actual infinity is that outside of which there is nothing else or left. As such, the actually infinite cannot be comprehended or grasped in its entirety. It represents what cannot be represented and thus stays on the border of a possible representation. It can be referred to only negatively or apophatically as ‘immense’ without any further qualifications, which is not even a concept. In this sense, the infinite immense is nothing.

The actually infinite might be known in its ‘is’, although not in its ‘what’, which cannot be grasped. This is what Descartes in the Meditations attempts to do, arguing that the existence, or ‘is’, of the actually infinite can be proven and thus known, but its essence, or the ‘what’, is ungraspable. For his purpose, this should suffice, since the Cartesian ego clarifies itself to itself in an act of thought that only thinks its very thinking but is ontologically grounded in the infinite: it is the infinite that makes the finite self-reflective thinking of oneself possible. ‘Immense’ thus names the unnamable and stands for non-being, which is hinted at by the withheld void at the end of the poem. Referring to the void of the Atomists, which is a paradoxical unitary non-being that exists emptily in its non-existence, allowing for the possibility of the multiple being(s) of the atoms, Simplicius calls the void ‘mere conception’ (μόνη ἐπίνοια), which means to designate something that is not properly referable, because it does not actually exist (In Physics 648.10). So the ‘epinoetic’ thought can be understood as thinking directed to that which can never be reached or properly thought. The epinoetic thinking is thinking without a (direct) object, is the thinking toward the immense as surpassing the thought and thus only obliquely slid along by the conception without a concept. For the infinite and the immeasurable is non-being, and as such does not exist and cannot be thought except indirectly and dimly reflected in a thinking that hopes to constitute being against an opposite or privative nothing.

Light. The title of Ungaretti’s poem is Mattina, ‘morning’, which suggests that I enlighten myself against the immense morning light that has just shone from darkness. And although the immense cannot be thought, and is thus approached by a strange kind of ‘epinoetic’ thinking, the immense in its transcendence can be considered a precondition for such thinking, and also of being. The language stops short of exploring this possibility, because language always deals with concretely defined and distinctly lit and outlined objects, acts, and situations. However, negatively, the nothing of the infinite as the unthinkable source of being can be hinted at, especially in poetry, which brings language to its limit and self-suspension. In Ungaretti’s case, it comes with a hint at lighting oneself from and by standing up to the infinite, which itself does not stand and cannot be located anywhere, because it is nothing and is thus not graspable in any (other) way. If the immense is perceived as, in, and through light, then, being immense, unthinkable, unseen, and preceding being, it cannot be distinguished from darkness, because no distinction as based on sameness and difference or on identity and non-identity can be thought yet. Indistinguishable from light, such darkness is not light and can be said to ‘be’ in its non-being beyond light (as in Dionysius the Areopagite’s The Mystical Theology 1–3). The source of light is not light and does not light itself, and the light itself cannot be seen. Only the lighted and enlighted can be seen. In order to see colours, hues, shapes, and outlines, one needs distinctions and gradations. But the immense uniform light does not have them. So the ‘enlightening’ by the immense is indistinguishable from the ‘endarkening’ or obscuring by it.

The immense might also be an overwhelming source of light, such as the burning and annihilating fire. It can be taken as the Biblical ‘consuming fire, a jealous God’ (Deuteronomy 4:24) that burns those who forget and neglect his commandments. Or it can also be taken as a light that dispels darkness and is a reflection of the immense and irrepresentable but luminiferous divine ‘glory’, which makes the enlivening light and clarifying lighting possible (Isaiah 9:2; 60:1). The immense can thus be considered an ontological quasar that is originated by an unfathomable black hole, an enigmatic source of light that burns and destroys everything that stands in its way. Yet, as nothing, it does not annihilate, because nothing is yet. Rather, the immense precludes a proper constitution of the ‘I’ that might be clarified from and by immense that might put this I into focus.

But Ungaretti’s hope that transpires in his poetic exclamation is that the immense might still allow for a response from me – emotional rather than cognitive or perceptive. Perhaps I will be filled with awe, joy, or fear. Yet, flooded by and from the immense, my response most probably will remain indistinguishable to myself and thus not really accountable for it.

Self-illumination. What does ‘m’illumino’, ‘illumining myself ’ mean, then? If I am the actor, the act, and the result of self-illuminating, it can have three different yet ultimately converging meanings.

1.

‘I illuminate myself ’. I illumine and lighten myself up from and in the light of the immense, and in this way enlighten myself. Yet, if the light is immense and superabundant and thus indistinguishable from darkness, it cannot enlighten me, and I cannot enlighten myself against and from within the immense. I appears in the act of illumination – but then immediately disappears, or rather, it is constantly striving for self-illumination without ever attaining it. Simultaneously (but not temporally), the immense also appears in and through the same act of my attempted self-illumination. Yet, because the immense is nothing – nothing that can be thought, described, or pointed at – it appears in its elusive disappearance. As a light indistinguishable from darkness, the immense precedes being and hence also precedes being-myself. Therefore, illuminating myself from and by the immense, I can never achieve self-illumination, which is thus indistinguishable from self-darkening.

2.

‘I clarify myself ’. I am not, I do not exist, before and until I clarify myself, make myself clear to myself. Self-clarification might suggest establishing the Cartesian ‘cogito’, when I come to clearly and distinctly understand that I cannot but exist when I am thinking, since my awareness of thinking is only possible if I exist. This thinking is the thinking without any object other than thinking and therefore is the thinking of nothing – nothing in particular, because in coming to think pure thought I liberate my thought from any thought. And yet, I cannot miss that I am thinking when I am trying not to think anything specific. This should mean that I think something, but since there is nothing else at this point except for my thinking, I have to be thinking myself. The Cartesian act of reflection that assures the existence of thought is thus thinking nothing, which turns out to be the pure awareness of the self as the ultimate achievement of cognitive self-transparence. If the illuminating self-thinking is eventually empty and thinks nothing, the joy of illumining myself is indistinguishable from fear, because nothing causes awe, anxiety, and fear. Nothing cannot be thought, and hence nothing can be thought in thinking about nothing, so the deceptively clear and self-evident self-thinking is an illusion, because I clarify myself for myself by, through, and from nothing, without establishing any I or self.

This is, then, an act of self-reflection that cannot be completed and performed. Hence, it is a non-act of clarifying myself for myself from the immense. Lighting myself up from the infinite ultimately obscures any self-clarification. What should arise in such a non-act is an ‘I’ that should be clear and clarified to itself. I bring – attempt to bring – myself back to myself. This myself does not exist before such an act. Being of I am who I am (cf. Exodus 3:14) should be the result of concentrating the immense (light) in a single focus, which now becomes ‘I’ and can say ‘I’ to and of itself. Yet, the self cannot be constituted from the immense, because I have no power to gather it in one point, for I do not exist yet. And if and when I do exist, I exist as finite, I finite myself, and thus cannot operate with the immensity of the infinite, except for symbolically or negatively. Rather, the immense should constitute me, but my own effort of turning it reflectively – in and by reflection – into an ‘I’ fails, because of the overwhelming and utterly indistinguishable character of the immense, of the light darkness, dark light, lightdarkness. This makes reflection impossible, as well as my (self-)enlightened existence. I keep existing always in the dark. The immense, therefore, never becomes the immense but is immense in its inescapable elusiveness.

The act of reflective self-illumination thus does not clarify anything, because, coming from the immense, this act is itself indefinite, empty, and is the non-act of self-obscuring by the incomprehensible, rather than of self-clarifying. This means that I do not and cannot exist as self-clarifying I, as making sense of myself from the perspective of the immense, which I assume and posit but can never reach. The self-clarifying self always stays out of focus, can never concentrate itself in one single focal point where it would finally come to full moral self-accountability, cognitive self-understanding, and ontological self-transparence. I cannot focalise myself into a self-transparent, self-clarified, and self-aware Cartesian ego as the ‘I’.

If self-reflection remains always unfocused and does not lead to the understanding of the self as an I, the attempt at self-clarification can only lead to the total destruction of the self. Self-reflection comes to nothing and does not match being. Self-clarification is self-obscuring and literally comes to nothing, and in this way nothing nothings through my attempt to make myself clear to myself by the nothing of the immense. Making myself clear is indistinguishable from complete transparency and invisibility, where there is nothing to be seen or distinguished in me. I thus enlighten myself into complete self-darkness.

Nothingness whispers through the poem, showing itself in hiding in the last missing stressed syllable that should be there – but is not. Grammatically, there is no ‘I’. The subject is missing. It never appears, for it cannot appear as self-clarified by the infinite. The self-clarifying reflection is an inevitably missed act of the unfinished and unfinishable play between non-being (the not yet shining light) and being (of the I that has to appear enlightened, clear, and full of light). Therefore, as a result of such an act of the failed self-reflective attempt, the ‘I’ is (am) always out of focus and entirely disappears in this non-act.

3.

‘I burn, blind, and annihilate myself ’. In lightening myself up from and by the immense I burn myself out. The infinite light that is indistinguishable from the indefinite darkness is overpowering and burns everything that could stand in its way. As a precondition of being, it can only allow being as finite and hiding from the direct burning light of the nothing of the immense. It becomes especially insuperable when I attempt to focus it in and on myself. By illuminating myself with and from the immense, I blind myself. I cannot see – or think clearly and distinctly. I burn myself out in the focus and thus remain unfocused or always out of the focus. I annihilate myself. I erase and evaporate myself. The attempt at measuring myself from and by the immeasurable turns out to be vain and leads only to the destruction of the self, of its distinctions, capacities, or attributions. The act of self-illumination is ultimately a non-act that amounts to an inevitably failed and missed act of the constitution of the self as a concentrated light of reason in the locus of being. Nothing is left. Nothing remains of the I that has already and forever been burnt out, erased, and obliterated by non-being.

M. K. Čiurlionis, Truth, 1905, pastel on paper

Dmitri Nikulin is a Professor of Philosophy at The New School for Social Research in New York. He is the author of a number of books, including Dialectic and Dialogue (2010), Comedy, Seriously (2014), The Concept of History (2017), Neoplatonism in Late Antiquity (2019), Facets of Modernity (2020), Critique of Bored Reason (2022), and Non-Being in Ancient Thought (forthcoming).

1 Giuseppe Ungaretti, ‘Mattina’, Santa Maria la Longa, 26 January 1917, in L’allegria: 1914–1919, Vita d’un uomo. Tutte le poesie. (Milan: Arnoldo Mondadori, 1969; Mondadori libri, 2016), p. 103; my translation.

2 E.g., Čiurlionis’ paintings The Truth, Spring, Mountain, as well as his musical pieces Sea and In the Forest.