Fragments of Čiurlionis

For the 150th anniversary of the composer of painting and music

Čiurlionis has become, for Lithuanians, something that absorbs and encapsulates almost everything – like a giant cosmic black hole. His posthumous legend and ever deepening myth unwittingly drown out the history of a real, rather Kafkaesque personality, and at the same time his diverse creative legacy. In fact, in the various texts written about Čiurlionis and in the countless interpretations of his music and paintings, there is a kind of avatar of Čiurlionis floating around, if not a whole flock of phantoms gathered in mysterious choirs, whose whispering seems to some to be the voice of Čiurlionis himself, supposedly speaking from the heights of eternity.

‘Who then would be the innovator in the case of Čiurlionis? God. After all, it was his innovation to send Čiurlionis. Let us remember: “The Holy Spirit speaks through the prophets.” We hear about this at every Mass. It is time to understand. It doesn’t hurt at least to feel it’, Vytautas Landsbergis, one of the most prolific Čiurlionis scholars, fervently states.

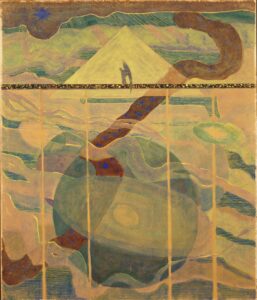

M. K. Čiurlionis, The Thought , 1904–1905, pastel on paper

POLITICS

Čiurlionis is, for Lithuanians, an important political phenomenon. The identification of Čiurlionis into the state has been going on for more than a century. The first wave began with the rescue of his paintings during the First World War, when they were taken to Moscow for safekeeping, and then, after being recovered with difficulty, returned to Lithuania, and purchased here, bringing almost all of the surviving paintings together in one place – with the establishment of the national Šarūnas Nakas (p. 115) 17 Čiurlionis Gallery in Kaunas in 1921. Finally, the practice of performing and publishing Čiurlionis’ music in Lithuania took off.

All this is interrupted by the Second World War, after which the fate of Čiurlionis hangs in the balance: the Russian occupiers treat Čiurlionis as a ‘reactionary mystic with schizophrenic delusions and extravagant psychopathy’, as a consequence of which, of course, his art should be disqualified. Fortunately, this does not happen, despite the idea of Lithuanian critics that Čiurlionis’s work is ‘an expression of the attitudes and psyche of the decaying bourgeoisie of the imperialist era.’

As Stalin’s post-war terror subsides, a second wave of Čiurlionis’ actualisation and further absorption into the state gradually emerges, at first somewhat more cautious, but no less significant. It is most closely associated with Čiurlionis in 1965 with the celebration of his 90th birthday, when many previously unknown phenomena associated with his name and his work appear. Reproductions of his paintings, even if of poor polygraphic quality, are published in abundance, spreading not only through Lithuania, but also into people’s households throughout the Soviet Union and even in the Eastern Bloc. Photographs of Čiurlionis’ paintings sometimes hang in the classrooms of music schools in various towns of the Soviet Empire and are presented to children as an example of what young people should emulate.

Čiurlionis’s 100th anniversary is extremely pompous, celebrated in excessive ways, and the most important event takes place not even in Lithuania, but in Moscow, on the stage of the Bolshoi Theatre, as the anniversary of a canonised artist who was important for the entire Soviet Empire. Several monuments to Čiurlionis are erected, but not in Vilnius: in all of them he is a grizzled old man, the patriarch of a suffering nation, who generally embodies the romantic ideal of the creator – in a way that everyone can understand.

The third wave, of course, is happening now, after Lithuania broke free from the grip of the empire in the 1990s and released Čiurlionis into the world without any restrictions. For Lithuanians, this is an opportunity to wipe off the stain of the Soviet legacy and to present the artist as an original and independent creator who undoubtedly deserves wider international recognition.

Čiurlionis is like a brand, with Čiurlionis chocolates, scarves, a concert hall in Kaunas built in his name, and Vilnius Airport, now renamed ‘Vilnius Čiurlionis International Airport’, and he often competes with contemporary artists in Lithuanian cultural export projects. One hears the constant refrain that he is ‘the only, true, unquestionable genius of our nation’, trying to patch up gaps in historical knowledge and unconsciously forming a cult around him like that of a pop star. Of course, inevitably, by levelling and trivialising everything.

M. K. Čiurlionis (second from left) and the Wolman Family in Anapa, Russia, 1905. Photographer unknown

PERSONALITY

There is not much direct information about Čiurlionis as a person. In those days, no one conducted any interviews or conversations, and Čiurlionis did not appear in literary circles, where he might have left a more documentary trace. Therefore, the most frequent reference is to his letters, which, unfortunately, cover only a few periods of his life. A lot of material was irretrievably lost during the First and Second World Wars, not only texts, but also Čiurlionis’ musical and artistic works. Many of the testimonies of his contemporaries were written down only a few decades later and are therefore laconic and fragmentary, imbued with the feeling and knowledge of a different era: we cannot always be sure that they are not stories that have been significantly altered in the remembering. But there are also, incidentally, a few journalistic texts by Čiurlionis that convey his attitude to the problems of Lithuanian culture of his era that were relevant to him.

However, it is also difficult to analyse Čiurlionis because his activities are so multifaceted, and his personality is like a maniacal collector: he is interested in an extremely wide range of spheres and activities, which he wants to try out, albeit fleetingly.

‘As he grew older, M. K. amassed a considerable library, which he kept in Druskininkai and which was used by his younger brothers and sisters. He was primarily interested in astronomy and cosmography, and Šarūnas Nakas (p. 116) 19 he studied mathematics, physics and chemistry to deepen his knowledge of them. Among the astronomical writers, M. K. was most impressed by Camille Flammarion’s descriptions of atmospheric phenomena. Later, he began to study history, geology and palaeontology in depth; he became interested in numismatics and, together with his brother Povilas Č., assembled large collections of old coins and minerals, to which he made abundant additions during his travels through the Caucasus’, states the fifth volume of the Lithuanian Encyclopaedia in 1937.

This tendency to collect and accumulate – undoubtedly, a tool of his original erudition – is also applied to his artistic work: finding something, laying it aside, putting it away, rejecting it, pulling it out again, and using it again. ‘I saw him painting in nature all day, then working at night, to finish his symphony The Sea …

I saw him fainting at the piano keys in Krynica [a resort in Poland]; he was so exhausted by the immense work. He played his symphony, corrected it and worked until he fainted’, says a friend of Čiurlionis about Čiurlionis’ working style at a plein-air workshop in the summer of 1906.

The desire to compose in sound gradually competes with an irresistible passion for painting, and for a time the two areas of Čiurlionis’ life combine quite harmoniously. However, the musical side begins to recede, and visual art begins to dominate. It is as if Čiurlionis discovers painting a much more suitable means of expressing his ideas than his music. And a hurricane of creativity engulfs the creator himself.

Čiurlionis eats poorly, he has not slept for ages, and one cigarette after another is stuck in his teeth. The same thing, year after year. Sometimes, it seems he is completely unable to look after himself. In the summers, he goes to his mother’s house in Druskininkai, where he spends the whole time trying to eat as much as he can. And then it is the same again. Wearing himself out without any restraint. A shortage of money that paralyses not only the nerves.

Periods of deep melancholy with acute bouts of depression. Creativity – in fiery interludes, periods of acute inspiration, improvising and very often not finishing a musical piece that has been started, as if it were a sketch that did not work out or offered nothing new. The author is terribly self-critical and ruthless, like a soldier wielding a sword on the battlefield.

When speaking about his years in Leipzig, he gets very agitated: ‘I heard my “bear noises”. You have no idea how much I’m chewed up by that whole quartet. If Reinecke won’t let me write anything new, I’ll probably drown myself.’

Carl Reinecke is Čiurlionis’ professor at the Leipzig Conservatoire, to whom he goes hoping to learn something more significant than from his previous professor at the Warsaw Conservatoire, Zygmunt Noskowski, the awakener of patriotic feelings, the composer of the first Polish symphonic poem ‘Steppe’. Unfortunately, his expectations are not fulfilled here either, so Čiurlionis learns much more in the library of the Peters publishing house, learning directly from the authorities: ‘… I have already rewritten the greater part of “Death” (49 pages). I like [Richard] Strauss more and more every time.’

This independence inevitably reinforces the feeling of loneliness, but also provokes bolder intellectual adventures that eventually lead to a world of innovative ideas: the silent music of painting, which is still difficult to describe today. For Čiurlionis, these supposedly different types of artistic expression merge and intermingle: he becomes the interdisciplinary artist of his time; so, to speak of separate fields in isolation from each other is problematic and not entirely accurate.

But everything has its painful price. Čiurlionis is exhausted by his ardent style of work, his complicated rhythm of life and overloaded daily routine, and is regularly struck by ever deepening nervous crises: ‘I am sitting at the trio from dawn. I don’t have the slightest desire. It’s even painful. Write something, or I’ll perish. If I get my diploma, I’ll quit music. I can’t work on anything, and I don’t want anything. I don’t want to look at anything, I don’t want to move and, worst of all, I don’t want to exist. And there is no way out.’

But sometimes it is completely the opposite – there are bursts of joy and enthusiasm when fantasising about the future: ‘We will give a concert at the Philharmonia, completely independent of anyone, we will hire a hall, an orchestra, etc. It will be good, right? In the autumn, I’ll probably organise my own exhibition at Zachęta. Something deep in my soul says it’s too early, but what can you do, everyone is persuading me.’

A man laying on a broken bed, 1905, photograph by M. K. Čiurlionis

SYMPHONIC POEMS

Čiurlionis composed the first and still the most popular Lithuanian orchestral works – the symphonic poems ‘In the Forest’ (1901) and ‘The Sea’ (1907) – but they were not performed during his lifetime. He wrote more symphonic works, but they did not survive – or have not yet been found.

Waves, winds, clouds, sea, forests, mountains, fields – the constant patterns of Čiurlionis’ world of images. That world is first and foremost refined by the composer’s musical intellect, formed in the milieu of Romantic music. Of course, the greatest influence is exerted by the Polish composer Chopin and the German Wagner: that is not exceptional at the end of the nineteenth century when Čiurlionis was studying at the Warsaw Institute of Music from 1892. This was, incidentally, the only higher education institution in the Russified former capital – now only the centre of a province – where the teaching was in Polish rather than Russian.

Čiurlionis’ ‘In the Forest’ is inevitably a work influenced by dreamy Polish romanticism, which also draws on the ideas of Wagner’s ‘Forest Murmurs’ from his opera ‘Siegfried’: in the idea, colour and atmosphere, and in the nature of the melodic motifs. When writing ‘In the Forest’, a sincere, simple and bright work in the style of Polish Romanticism, Čiurlionis does not yet suspect that he is composing the first national Lithuanian symphonic work: in his consciousness of the time, Lithuanianness meant only a specific historical and geographical localism.

But what is more important for him here is lyrical self-expression, the ability to create a soundscape, and, ultimately, to equal or even slightly surpass his teachers. The forest of musical romantics is not that different from painting: both follow the logic of easily recognisable plots and situations. Later, he often paints the forest, a space filled with Romantic symbols, and the forest for him almost never becomes the labyrinth of fear and unease favoured by the Symbolists, and soon after by the Surrealists.

After his studies in Leipzig, Čiurlionis is already quite different. Now, like almost all composers of his generation, his greatest authority is Richard Strauss. Working intensively, Čiurlionis composes ‘The Sea’ at exactly the same time as Debussy. Čiurlionis is probably unaware of the real boom in symphonic marine art in France – he is sceptical about French new art, identifying no phenomena in it of particular interest.

Čiurlionis’ ‘The Sea’ seems to take us back to the end of the nineteenth century, and perhaps this is related to a kind of social selfpreservation for the composer: moving away from standard language towards some less expected modernity always provokes a negative reaction from listeners, but here Čiurlionis is pursuing different goals, and recognition is very important to him. Undoubtedly, when writing for orchestra, Čiurlionis does not feel as solid as when working with piano music: the practice of his orchestral composition is much more modest, his musical language is less flexible, and his ideas much more conservative. ‘

The Sea’ is the greatest symphonic work of Lithuanian national music, the apotheosis of late national Romanticism. It is music that migrates between the German, Slavic and Nordic worlds with hints of intonation and subtly changing styles of episodes: it is precisely this symbiosis that becomes the benchmark of Lithuanianness in music. The geopolitical fate of the ‘Lithuanian sound’, which has remained essentially unchanged in the century following Čiurlionis’ death, is thus determined in an integrated way.

M. K. Čiurlionis, The Altar , 1909, tempera on cardboard

BLACK SUN

The penchant for painting, which slowly transforms into a passion and ambition to learn to do it professionally, is a factor that transforms Čiurlionis as an artist: the practice of creating plastic forms influences the music he writes, just as the contrapuntal structuring influences the nature of his paintings.

‘The painter who interested me most – perhaps the most talented representative of the Russian school at the beginning of this Šarūnas Nakas (p. 118) 23 century – was the Lithuanian M. K. Čiurlionis. I had bought a beautiful painting of his in 1908, partly at the suggestion of Benois. It depicted a row of pyramids, painted in pale, pearlescent ink, receding towards the horizon at the top, but in a crescendo rather than a diminuendo, as orthodox perspective would require. In fact, that painting was part of my life, and I remember it vividly to this day, even though it was lost fifty years ago in Ustyluh.’

So says the famous Igor Stravinsky in an interview with Robert Craft, published in New York in 1962 in the book of conversations Memories and Commentaries, recalling a painting by Čiurlionis, Baladé (Black Sun), which he had owned but lost, and which has still not been found.

Stravinsky is seven years younger than Čiurlionis – they belong to different cultures and galaxies which pass by each other, as it were, and their lives unfold in an extremely different way. However, Stravinsky does not consider the Lithuanians as an independent nation, but only as one part of the Slavic world. Therefore, for Stravinsky, a follower of the Russian imperial tradition, Čiurlionis is the most talented representative of the Russian school. Stravinsky conducts a concert of his works in Kaunas, the then provisional capital of Lithuania, in the early spring of 1934, but even this does not change his understanding.

The static, rather introverted, cold and harsh musical world of the late Čiurlionis (1904–1909) – almost exclusively piano, one could say – is almost the total opposite of the flaming and sparkling music of the (young) Stravinsky of the same period. However, this impression is somewhat misleading, because the multi-faceted Stravinsky would later write music of a completely different character. One should not forget the lasting impression made on Stravinsky by Čiurlionis’ Black Sun – even after so many years: one of the paintings that creates a rather ominous atmosphere, close to Čiurlionis’ late music, and which is distinguished by a clear, almost declaratively geometrical – if not downright occult – structuring.

And yet, in 1912, after Čiurlionis’ death, Stravinsky wrote a small cantata for choir and orchestra, ‘King of the Stars’, based on a poem by Konstantin Balmont, the poetic text of which is like a literary description of the plot of one of Čiurlionis’ paintings: with cosmic vastness, rainbow colours and a giant mysterious hero descending straight from the heavens.

They have other things in common. In ‘The Chronicle of My Life’ (1935), Stravinsky nostalgically recalls ‘the singing of the women of the neighbouring village’. ‘There were a great many of them’, says Stravinsky, ‘and they sang in unison every evening. To this day, I clearly remember that singing and the way they sang it. When I used to sing those songs at home, imitating them, the adults praised the trueness of my ear.’

A little earlier, in the book In Lithuania written by his wife Sofija Kymantaitė-Čiurlionienė, published in 1910, Čiurlionis writes: ‘There are many such melodies; only a Lithuanian can understand them and feel them properly, when, having heard them somewhere in the fields, the singer, unprompted, uncommanded, sings them for himself. Some strange lamentation, wailing, longing, tears of the heart can be heard. These are the oldest songs.’

REVOLVER

Here is a quotation from a letter written by Čiurlionis to his brother Povilas in 1906: ‘I always kept a loaded revolver in my pocket.’

Yes, these are Čiurlionis’s own words, without any distortions, although taken out of the context of the letter. In 1905, while attending a plein-air festival in Latvia, he became entangled in revolutionary events and had a completely new experience:

‘We were running empty-handed, but the Jews had revolvers, so that every one of us was armed from head to foot with a revolver. We go to where the looting is happening, and there are literally several dozen boys who greet us with double-barreled guns. We set on them with all our might with the battle cry, “Disperse!” When that doesn’t work, we shoot into the air, and when that doesn’t work, we fire at them, we simply fire at their heads; the “Black Hundreds” run away, and we chase them through the fields and meadows, shouting and shooting … Well, we won the fight honourably – there were not even any wounded on our side, but on the side of the “Black Hundreds” there were two casualties, one of whom turned out later to be stone dead. I stayed three weeks in Rybiniškės and learned to play billiards, but I always kept a loaded revolver in my pocket (the others did too).’

I wonder how much that revolver of Čiurlionis would be worth at auction now if somebody found it …?

IDÉE FIXE IN MUSIC

Čiurlionis’s music, which is ‘enveloped’ by his painting, evolves in an interesting way. From around 1904 onwards, Čiurlionis writes slightly strange preludes for piano, no longer born from spontaneous romantic improvisations and typical rhetorical figures of the period, but constructed rationally, like enigmatic crosswords. The music is somehow understated, as if incidental, without any external virtuosity or desire to please the salon audience. Satie does something similar at this time, but for Čiurlionis, the Frenchman’s desire to shock in his own way or even to irritate is probably alien.

We would say now that Čiurlionis was exploring the possibilities of the exact repetition of small interval segments throughout a work from beginning to end. It is not a musical theme or a melodic fragment, but a kind of molecule, a constructive thread of composition, onto which other voices are quite freely woven. Having been very interested in the technique of counterpoint during his studies (which is why he went to Leipzig to study further), Čiurlionis ferments a new method of composition, in some respects – admittedly, very distantly – related to the serial method that appeared much later. This is not a unique practice: a number of young composers at the beginning of the century are interested in it, but Čiurlionis is unaware of the others, and the result is, therefore, unlike anything else.

In this way, works with a kind of idée fixe at their core are created little by little, perhaps the strangest of which are two cycles of variations for piano, based on the letters of the names and surnames of familiar people: ‘Sefaa Esec’ (1904) and ‘Besacas’ (1904–1905). Čiurlionis continues this type of experimentation in his later years, structural advancements that many of his contemporaries could not even imagine. It is a pity that this is not a completed technique and aesthetic; everything is only in its initial, but intriguing stage. It is impossible to guess where it might have led – it only lasts very briefly.

Of course, the interest in this started around 1960. At that time, there was an attempt to find similar things in the music of many composers of the early twentieth century – and often successfully. This pursuit seemed to echo the relentless search for the abstract in painting at the same time, and here, too, Čiurlionis attracted considerable attention. It is merely strange that almost nobody has tried to view these phenomena simultaneously, as almost unidirectional efforts at a particular time to transform the body of music and art – with all the possible discoveries and inevitable perversions. Čiurlionis is very special here: he pursued this convincingly in both mediums.

Thus, his late piano works perhaps come closest to the themes and forms that Čiurlionis also sought to realise in painting. They share a clarity of idea and an atmosphere of twilight, a transcendent feeling and a rather laconic, almost biblical, language. In both music and painting, a sense of space is very important to Čiurlionis: in music, this is embodied in the abundance of low tones and the cascades of sound that cover almost the entire keyboard. The idea of painting cycles is echoed in the cycles of short, expressive piano pieces: they are characterised by an unrelenting tension, and the mood of each piece is sustained throughout the work.

It is very difficult to call this music Čiurlionis’ late work: in 1904, when this period began, he was only twenty-eight years old, and in 1909, when he finished composing, he was just thirty-four.

By the way, the ‘imprints’ of musical compositions mentioned above – those ‘stubborn’ mysterious molecules – are also reflected in some of Čiurlionis’ paintings. One can see strange astrological signs or symbols, even initials and a secret script, which is usually inlaid in architectural structures: but they are also very similar to the traces of graffiti or tattoos that young people leave nowadays, in places that are not quite appropriate – even on their bodies.

THREAT OF ARREST

Čiurlionis has an extraordinary friend, a true soulmate, although they are very different in appearance and temperament. This is Eugeniusz Morawski, who studies composition and painting with Čiurlionis in Warsaw. They spend a great deal of time together, sharing ideas, joking, travelling, and making fun of each other. Morawski supports Čiurlionis financially so that he does not live in semi-starvation. Čiurlionis greatly values his friend, perhaps the most important person in his life up to then. With him he visits the Crimea and the Caucasus, perhaps the most significant journeys in Čiurlionis’ biography.

Morawski secretly belongs to a revolutionary faction of the Polish Socialist Party, which is planning and carrying out acts of terror against the Tsarist administration and police. Very little is known about Morawski’s role in the party during the turbulent times of the 1905 revolution. At the end of 1907 he was arrested and sentenced to a Siberian penal colony. His friends inform Čiurlionis of his friend’s arrest, and without hesitation, he flees from Warsaw to his parents in Druskininkai, where he anxiously awaits the gendarmes.

Although they never show up, it remains unclear what Čiurlionis was so afraid of. What possible links could he have had with the Polish revolutionaries?

Morawski’s father sells all his real estate and pays a bribe of record size to the Tsar’s governor. Siberian exile is replaced by a promise to go to London and never return to Poland.

Čiurlionis and Morawski, who never made it to London but stayed in Paris, never met again. During the Second World War, a fire in Morawski’s house in Warsaw destroyed almost all of Morawski’s creative legacy, as well as many of Čiurlionis’ letters, photographs, and several paintings.

M. K. Čiurlionis and Eugeniusz Morawski, 1905 Photographer unknown

NIGHTINGALE

‘Not only do I love them and admire these wonderful paintings, but I believe that my musical goals are really close to the aspirations of this brilliant painter’, Olivier Messiaen wrote in 1964.

Messiaen, of course, has no idea that as early as 1905, Čiurlionis composed a miniature for piano, ‘Nightingale’, in which he uses authentic passages sung by a nightingale. The young composer’s breakthrough into a radically new world of sound is simply astonishing. This music is like an objective document of observation of nature, almost without any additional embellishment. Incidentally, Messiaen was not yet even born by then.

‘The very titles of the works – Sonata of the Sun, Sonata of the Spring, Sonata of the Sea, Sonata of the Stars, all divided into four pictures: Allegro, Andante, Scherzo, Finale (as in a sonata or symphony) – show the degree to which his painting was a painting of music’, Messiaen recalls on another occasion.

Messiaen is very fond of Čiurlionis and even talks about him at his 70th anniversary conference at Notre Dame in Paris. But it takes time for Lithuanians living behind the Iron Curtain to find out about this.

M. K. Čiurlionis, Nightingale (1905, from music manuscript book)

THE VILNIUS STAGE

Čiurlionis scarcely lives in Lithuania. He grows up here, but goes to Warsaw to study and lives there for almost 12 years, spending holidays in Lithuania with his parents in Druskininkai and one season at the Leipzig Conservatoire.

The modernisation of Vilnius in the early twentieth century was one-dimensional. Technologically, it was a third-class city of the Russian Empire, even though it was squeezed into the important transit of the railway St. Petersburg–Warsaw–Berlin. Socially and politically, it was a heavily damaged area whose history in the nineteenth century occasionally makes one shudder. The Tsarist authorities closed Vilnius University in 1832, the archives and libraries were liquidated, and the official language was only Russian. After 1864, even the construction of churches was banned, some of them were closed, demolished and converted into Orthodox churches, warehouses and hospitals.

Due to the peculiarities of the Tsar’s policies, about 40% of the population of Vilnius is Jewish; the rest are Poles, Hungarians, Russians, and the number of Lithuanians is decreasing. Around 1900, only about 2 % were Lithuanians. The name ‘Lithuania’ is not mentioned at all, and Lithuanian writing in Latin characters has been banned for 40 years. Cultural life is modest, dominated by touring companies that rival both the Vilnius City Theatre, which produces mainly Russian works and Italian operas, and the few salons for lovers of art.

Čiurlionis does not speak Lithuanian because almost no one in his circle speaks it. However, in 1906, swept up by the wave of rising patriotism, he dedicates ‘all his past and future works’ to Lithuania without even planning to live there. It is possible that for Čiurlionis, this is simply a grand utopia, created by the efforts of many people, to which he feels the need to contribute.

Čiurlionis, who speaks Polish and Russian, is a typical Lithuanian city-dweller of those times, with the potential to be caught in the intertwined cultures and to reap all kinds of benefits from them. The city is, for him, indispensable. Only there can he find work of one kind or another, visit exhibitions, listen to concerts and have someone to talk to about it. This in no way contradicts the fact that his music and his earliest art are often associated with nature, the forest, the sea, birds, pastoral scenes and landscapes: many Romantics live one kind of real life in a concrete and often quite unpoetic environment, and another kind of real life, sensitive, intimate, sentimental and sublime, in their visions and works.

Čiurlionis first appears in Vilnius at the end of 1906, where he takes part in the First Exhibition of Lithuanian Art, organised by Antanas Žmuidzinavičius and Petras Rimša. This colourful event brings together artists of all ranks who consider themselves Lithuanians. Not all of them are professional artists, but the patriotic resolve of the artists is more important, and the organisers are very tolerant of their 34 aesthetic level. The exhibition is not ignored by the Tsar’s governor and the multiethnic public of Vilnius: Poles, Belarusians, Latvians.

Čiurlionis, who has come specially from Warsaw, puts a lot of work into preparing the exhibition’s displays. He manages to bring his whole family from Druskininkai to the opening, even his small children. Čiurlionis has much to be proud of, as 33 of his paintings are exhibited, all of which are distinguished by their style, including the particularly original cycle The Creation of the World.

After spending over a week in Vilnius, Čiurlionis returns to Warsaw, where he has been working and living for several years. However, Vilnius stays on his mind, and six months later, he writes in a letter to his patron: ‘I want to move to Vilnius permanently.’

He speaks quite frankly, stating: ‘Lithuanian music, we can say with confidence, has a future ahead of it, but today it does not exist at all. We are lagging far behind everyone. People know about the music of the Tyroleans, the Gypsies, the Turks, the Arabs, the Ukrainians, but no Frenchman or Englishman has ever dreamt of Lithuanian music.’ And he says even more critically: ‘We have been asleep for centuries, oppressed by political conditions, and today, in the days of our revival, our own ineptness prevents us from succeeding.’

Čiurlionis’ arrival in Vilnius is very important: he is active in all fields – art, music and organisational matters, but it soon becomes clear that there are practically no personalities of his level in Vilnius, and he has no one to discuss things with as an equal. The intellectual level of the organisers and participants of Lithuanian evenings is radically different from that of the infinitely more advanced Čiurlionis, whose wealth of knowledge and experience can barely connect with Lithuania.

It is clear that Čiurlionis’ determination to move to Vilnius is a much broader ambition than just the Lithuanianisation of Vilnius culture. Čiurlionis is a European with extensive experience and a fairly modern mindset. So his coming to Vilnius is also an ideological manifesto of modernity, an attempt to realise his ideas in a very ungrateful, but at the same time attractive, social environment. This is an original and important experiment in modernising and actualising not only national elements, but also life itself. No matter that it lasts only a few months. Even in that time, it highlights, albeit stutteringly, a number of problems that sometimes take a century to solve.

In Vilnius Čiurlionis’ versatile managerial talent is manifested. He skilfully directs the Lithuanian ‘Vilniaus Kankliai’ Choir, harmonises a number of Lithuanian songs for it, and teaches the singers music theory. There are no shortage of problems there because only a few people are professionals, and some even have severe hearing problems. Čiurlionis is demanding and does not hesitate to replace the less talented Lithuanians with more talented Poles or Russians, for which he is seriously reproached.

While living in Vilnius, Čiurlionis paints four sonatas, later known as Sonata of the Serpent, Sonata of the Sun, Sonata of the Sea, and Sonata of the Stars. These are probably the works that required the greatest efforts of concentration and imagination. They not only stand out from the context of Lithuanian art of the time, but in their conceptual and evocative nature they surpass many of the Symbolist and visionary painters. The creation of soundless music can perhaps be seen as the essential idea of such sonatas, if one looks at it from a formalist rather than literary perspective. It is evident that such a specific process exhausts Čiurlionis. He often overworks himself and writes hardly any music.

However, it was in Vilnius that he created perhaps his most impressive and visual masterpiece of marine art for piano – the triptych of small seascapes ‘Marės’. It is surprising how Čiurlionis manages to migrate between such different fields of activity – art, composition, conducting a choir, curating exhibitions – and not lose his ability to concentrate so fixedly.

SOFIJA

Sofija Kymantaitė is the first and only woman with whom Čiurlionis decides to live. They meet at a patriotic event in Vilnius, and Čiurlionis immediately decides that Sofija will teach him Lithuanian. Those lessons mark the beginning of a strong love that profoundly affects and greatly inspires Čiurlionis.

The lovers have many common interests, which makes communication easy and intoxicating. For Čiurlionis, Sofija is the embodiment of his dreams and expectations. When they are not together, they write passionate letters to each other. They begin in their own way to direct their future together. They share serious ambitions, are quite spontaneous, and like gentle humour.

Sofija is incomparably more capable of navigating the world of Lithuanian culture, so Čiurlionis, who has settled in Vilnius, finds her help invaluable.

How much time do they spend together? Very little, just a few months. This is not an easy ordeal for Čiurlionis, who is used to a different environment in Warsaw, the company of male friends, and a reclusive way of working.

He marries Sofija and wants to make her happy, but his desperate financial situation creates endless difficulties. Čiurlionis sees only one solution: to go to the biggest city possible and try to sell his paintings. His intuition tells him that this is a necessary step.

THE OPERA THAT DOESN’T GET WRITTEN

Sofija is a literary woman, so it is not a surprise that she dreams of writing an opera with Čiurlionis. Incidentally, Čiurlionis has been thinking about this since 1906: ‘I intend to write a Lithuanian opera.’

Sofija writes a libretto about the goddess Juratė, the legendary ruler of the Baltic depths, who falls in love with and kills the fisherman Kastytis. The theme of the sea is very close to Čiurlionis’ heart, and here he is offered a world of mermaids, sirens, melusines and other water creatures, which was quite popular in Romantic art. Čiurlionis says exultedly: ‘I have received your letters and [the libretto of ] “Juratė”! “Juratė” is really growing on me, and today I have already heard a little music in it.’

The libretto has not survived, but according to accounts which have, it was much more of a fairy tale than some variation of the Wagnerian Tristan und Isolde. Lithuanian society in Vilnius at that time did not have the resources to realise such a work. Lithuanian-language theatre was at a stage of absolute amateurism and had only just been legalised when the Tsar lifted the 40-year ban on the Lithuanian language. Thus, if the writers of an opera hoped to put it on in Vilnius, they inevitably had to accept very modest conditions.

Čiurlionis improvised something, wrote something down, and communicated something to Sofija. At the very beginning, he was planning a choral fugue. Might it have been an oratorio opera? He saw a lot of things through the perspective of a choir, because he had already had practice in that. But in his work – at least in his surviving work – there was no female voice. There was no theatricality, no scenes with dialogue. What type of theatre would have emerged from this?

M. K. Čiurlionis, Fugue (from diptych Prelude. Fugue, 1908), tempera on paper

The opera does not provide a solution to the literary problem. It is as if some more serious challenge is required, with some greater depth. Čiurlionis doesn’t seem to have this. He would hardly have been interested in a provincial outcome. His paintings of that period belong to a completely different order. And if one can occasionally see in them some semblance of a possible stage scenario, there is absolutely no reflection of the usual theatre of the time, with its obligatorily forced rhetoric and insistent psychologism.

‘Juratė’ was never written.

DEPARTURE FROM VILNIUS

While living in Vilnius, Čiurlionis says: ‘Generally speaking, relations with my Lithuanian brothers are very difficult. It is almost impossible to work together for the good of society. Everyone, however stupid, pretends to know a lot, and the intelligent people who could really do something are looked upon with suspicion and disfavour. This is not so much out of malice as a lack of education and understanding. We do not really have our own society yet, it is still being formed.’

Čiurlionis does not live even a year in Vilnius. He arrives here and leaves again for somewhere else very quickly. He flies several times to St. Petersburg, and he makes some arrangements for exhibitions in Warsaw. All in all, when looking at his short biography, it is impossible to ignore the fact that he is a man who does not stay in one place. The frequent travelling does not seem to exhaust or bore him.

However, Vilnius has a special place in his life. It is linked to his Lithuanianness and desire to do something extraordinary in that area. But in spite of everything – his love and his marriage that resulted, the authority he has earned, and the new opportunities that are perhaps opening up – Čiurlionis leaves for the imperial capital. His conscience tells him that it is not worth wasting his time.

The painter Antanas Žmuidzinavičius writes in his memoirs: ‘In 1910, on his way from Druskininkai to Petrapilis, Čiurlionis stopped in Vilnius. We took a long walk with him along the banks of the Neris and talked about various matters concerning the revival of Lithuanian art. He was nervous and feverish. He was designing the most magnificent Palace of Art in Vilnius, a huge theatre, a philharmonic. He was happy that everything was going well and should continue to go well. He calmed down as he said goodbye, said his simple “don’t get upset” as usual, and the unpleasant impression was smoothed over. “Listen”, he said, “in all artistic matters and in the work of the Society of Arts, from today, I give you carte blanche. On the Board, you had best replace me with another member. I am going away and I will probably never come back.” I tried to protest, but he just waved his hands in a strangely agitated manner and disappeared into the carriage. He never came back. Yes, he did come back – in a coffin.’

SONATAS

M. K. Čiurlionis, Sonata No. 6 (Sonata of the Stars, 1908). Allegro, tempera on paper

When it comes to Čiurlionis’ painting cycles, his seven ‘Sonatas’ are the most notable. It is safe to say that these are Čiurlionis’ strongest works. In them, the synaesthetic genius of the visionary reveals itself most comprehensively and persuasively.

Although mountains of texts have been written about them, the silent sonatas are intended for contemplation, not interpretation. At least not literally: their very specific origin, oscillating between the auditory and visual worlds, would require an adequate vocabulary that has not yet been developed. Therefore, one can only talk about the things around or Šarūnas Nakas (p. 125) 39 behind the Sonatas: straightforward deconstruction of them often leads to absurd confusion and frustration without any clearer understanding.

These Sonatas are not worth cutting with Beethovenian knives. They are not a transplantation of musical schemes into images. The frequent attempts to identify direct links to melodies and counterpoints of Čiurlionis’ music demonstrate only that those trying to do this have little interest in other music of the world and more general dynamic forms that are always possible to convey in some graphic way. To look for themes, expositions and reprises in the paintings of Čiurlionis, which are given musical titles, is almost the same as looking for them in floating clouds and Byzantine icons.

Čiurlionis’ Sonatas are music of silence, created for the eyes and the imagination. And, of course, this is a metaphorical rather than a direct translation of the idea of the sonata into an image.

M. K. Čiurlionis, Sonata No. 6 (Sonata of the Stars). Andante, tempera on paper

Čiurlionis devotes himself to painting at the expense of his music, not absolutely, of course, but more and more by working as a painter. He cannot help but feel that the things he reveals in the world of images he has not yet succeeded in doing in music. In modern terms, he lacks the tools to convey the kind of content and ideas that he has already done in painting. And these are extraordinary, often cosmic spaces, mysterious horizons, dances of stars, phantasmagoric cities, signs of ancient civilisations, and occult objects. And plasticity, which is becoming in its own way more laconic, more precise, and more subject to the influences of Eastern cultures.

Čiurlionis therefore simply chooses silence for its own sake. One can assume that this was temporary because no one knows how his musical evolution might have developed in the future had he not fallen ill and succumbed to an early death.

As his painting becomes more and more impressive, Čiurlionis almost stops writing music completely. Who knows, perhaps this is his way of entering a great pause – a long silence after which he will speak in a completely new way.

FROM LITHUANIA OR FROM VILNIUS

Čiurlionis always stands somewhere close to Lithuanian art, however strange it may sound to some. In fact, he never follows any authorities of Lithuanian art and culture. His reference points are completely different, in the art of other countries and times, although he is increasingly taken up with the aspiration to be contemporary. Čiurlionis is an artist from Warsaw, who thinks in fashionable dimensions, looking around Europe and fully aware of the realities of the Russian Empire of the time. That is why he migrates from Warsaw to St. Petersburg, staying only briefly in Vilnius, which at that moment offers him little.

But there is another side. One may recall Czesław Miłosz’s rather caustic remark that the modern Lithuanian nation is a linguistic product. In an interview with Lithuanian television, Miłosz stated that Lithuanians had only separated themselves linguistically from the expanding Polish ethnos, remaining essentially the same as they were before, but having created for themselves new political doctrines and ideologies.

One has to admit that the case of Čiurlionis at least partially illustrates this: his ideological authorities are Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki, and he is also greatly influenced by the music of Chopin and Polish Romanticism in general. After all, Čiurlionis speaks and writes in Polish, having spent much of his life in Poland. But he also persists in learning Lithuanian when he decides to be Lithuanian. And incidentally, he promises to donate all his paintings to the House of the Nation in Vilnius.

But is Čiurlionis really creating a Lithuanian style and ideology if right from the outset it is so mixed and complicated? Doesn’t his Quixoticism mean something a little different? And what does his rather tumultuous invasion of a city with almost no Lithuanians say? In general, how do we reconcile his intricate balancing act between the clearly conservative Lithuanianness of the time and the rather radical pro-European innovativeness?

Čiurlionis seems to be creating a Vilnius style. A style in which Lithuania is only one of the important segments. A style that is still not Šarūnas Nakas 41 absolutely clear to Lithuanians if they rely on the traditional patriarchal conception of Lithuanianness. Čiurlionis’ style is incomparably more complex, integral and universal than the vast majority of Lithuanian artists of his era. And such a style, containing a myriad of contradictory factors and possibilities, is only possessed in Lithuania by Vilnius. It is a synthetic style, embracing things that are familiar and things that have been brought from nowhere recognisable, an enigmatic sort of archaicism, and a multitude of invasive components from different periods. A style that has long been created in Vilnius by Lithuanians, Poles, Belarusians, Russians, Jews, Italians, Germans and Swedes. With all the ideological, aesthetic and political complications.

TWILIGHT OF THE NORTH

M. K. Čiurlionis, A vignette for Lithuanian folk song (Subatos vakarelį ), 1909

‘I like St. Petersburg; a granite city, with a sky like granite – the mist is saturated with curses and the stench of vodka, the faces are mostly sincere, the eyes are childlike, and there is so much misery here – oh my God!’ – writes Čiurlionis in a letter to his then fianc.e Sofija Kymantaitė at the end of August 1908, when he arrives in search of happiness in the capital of the boundless Russian empire: the third most populous city in Europe, one of the world’s most important centres of modernising art and culture which was at that time rivalled only by Paris, Vienna, London and Berlin.

While living in Vilnius, Čiurlionis makes several trips to St. Petersburg. These are by no means romantic or tourist trips. Čiurlionis has many business interests that can only be realised in the environment of a megalopolis. The maximum density of ideas, their greatest possible circulation, the most inventive colleagues – all these are the best stimulants. Incidentally, the famous Vilnius composer Stanisław Moniuszko had done the same thing several decades years earlier, when he also travelled many times to St. Petersburg to look for opportunities to establish himself there.

Of course, to have a look around the world of music is only one, and perhaps not even the most important, purpose of Čiurlionis’ visits to St. Petersburg. He is clearly now much more concerned with the sphere of art and the possibility of earning money from the sale of his paintings. He wants to make a living from his creative work and to be recognised. Unfortunately, in his year and a half in St. Petersburg, Čiurlionis does not seem to have sold a single painting – at least he makes no mention of it. And this, to his greatest misfortune, ends in real disaster. However, until the very end, Čiurlionis remains stoic, never giving up hope of somehow breaking through to where he thinks he deserves to be.

New art occupies an important place in St. Petersburg. There is no shortage of exhibitions, concerts and presentations, about which the public and the sharp-tongued critics are accurately informed. One of the most interesting cycles, running from 1900 to 1912, is the Contemporary Music Soir.es, which systematically showcases the most interesting manifestations of new music and provides a platform for composers and their works.

In November 1908, Čiurlionis attends one of the Contemporary Music Soir.es, immediately admitting: ‘… I liked it.’ And with unexpected boldness, without waiting for others to help and introduce him, Čiurlionis goes himself to the organiser of the cycle:

‘I rewrote a few of the better (older) pieces and went to him. […] I played them. […] My things will be performed at the concert. Encouraged and delighted by all this, I rewrote the things that I thought were the best, you know, my ‘Sea Pieces’. The committee of some four less sympathetic gentlemen gave a much cooler reception to these pieces of mine, because I was playing by myself, and I played fatally, and I think they’ve postponed the performance of my compositions. They gave me a lot of praise, of course, but they didn’t appear to understand exactly what wasn’t good, and what was really mine and new – I’m left with that moral satisfaction (sad, by the way, because I want them to understand me). However, I don’t think I’m going to make any compromises with myself.’

Incidentally, the word ‘fatally’ here should be understood with its typical Polish connotation: ‘badly, terribly, very poorly’. Nevertheless, Čiurlionis’ works are included in the cycle of Contemporary Music Soir.es concert on 28 January, only this time they are not played by the composer himself, but by the pianist Jovanović, a frequent guest at these concerts, who was famous as a pupil of Camille Saint-Saens.

And it is quite interesting to note that only a month earlier, the 17-year-old Sergei Prokofiev and 27-year-old Nikolai Miaskovsky had made their debuts at the same concert, and the year before that, the 25-year-old Igor Stravinsky. Čiurlionis’s participation in the Contemporary Music Soir.es is a clear indication of his possible calibration in Russian musical life at the time: much is undoubtedly expected of him, and he is therefore given a serious chance. He immediately Šarūnas Nakas 83 finds himself among the most promising, and without any reservations. But does he fully understand this?

The very next month, on 24 February 1909, Čiurlionis’s piano music is played at another important event – a concert during the ‘Salon’ exhibition, along with the latest works by Scriabin, Mettner, Rachmaninov and Stravinsky. It is important to recall here that the exhibition also featured paintings by Čiurlionis, and thus drew attention to the fact that Čiurlionis was expressing himself in two fields at once. By the way, in terms of recognition and resonance, there has been much more interest in Čiurlionis’ paintings. He has been accepted into the Union of Russian Artists, he has participated in its exhibitions, and he has been encouraged to create new paintings for other exhibitions. But unfortunately, without any honorarium. As they say, for honour. Čiurlionis is sinking into intolerable poverty, but still hopes that better times are just around the corner.

Having settled in St. Petersburg, Čiurlionis has almost no time for more serious musical work and writing new compositions. And even though Čiurlionis is now painting his best paintings one after the other, things are not going quite as he would like. And the reasons are fundamental. On the one hand, Čiurlionis is often irritated by the overtly bourgeois work of many artists, and on the other hand, his tastes differ significantly from those of the local Russian, having been formed far from the imperial capital and in a field of quite different cultural influences. Relations with the Symbolists of St. Petersburg, from whom much was expected, are intermittent, mostly only official and fragmentary. Čiurlionis associates with the ‘Mir iskusstva’ group of artists, which had at the time relatively little influence in St. Petersburg at the time, but these contacts simply do not stimulate him.

Nevertheless, having come to St. Petersburg as an artist with fully formed views, Čiurlionis probably could not have expected any greater, let alone spontaneous, favour. His excessive creative independence and the closed nature of his personality do not help Čiurlionis to establish himself and to receive much-needed commissions. It forces him to hustle as fast as he can, torn between random earnings and almost random people.

Čiurlionis has to communicate mainly with the Lithuanians of St. Petersburg. In a city of one and a half million inhabitants, there is no shortage of Lithuanians and their organisations. However, Čiurlionis’ art was completely irrelevant and unnecessary to them – worse than in Vilnius.

‘I have just returned from a “cultural” (?) Lithuanian evening where I played my compositions’, Čiurlionis says in a letter. ‘Of course, the audience had high expectations and was therefore completely disappointed. They asked me for something more cheerful, they almost asked me to give them more peace.’

Although Čiurlionis is faring really poorly in St. Petersburg, the city attracts him like a magnet. He spends more than eight months of his life there, and these are among the most significant episodes of his biography in creative terms. By the way, Čiurlionis first came to St. Petersburg in 1906 as a student at the Warsaw School of Art, where he exhibited his painting cycles Creation of the World, A Day, Storm and the no longer extant diptych Rex. Russian critics pay some attention to his work, and perhaps this is what encourages Čiurlionis to try to establish himself in the St. Petersburg art world.

And so in 1908, Čiurlionis goes to St Petersburg twice. The summer visit is seemingly fruitless, but in the autumn several promising contacts are made, and Čiurlionis is noticed both as a painter and a composer.

Then, after a short trip to Lithuania and his marriage to Sofija Kymantaitė, Čiurlionis immediately returns to St. Petersburg and takes part in several exhibitions and concerts. However, neither then nor later is he able to find any steady income.

His last visit at the end of 1909 takes a dramatic turn. Although Čiurlionis is offered a job with the St. Petersburg Lithuanian Choir, he is increasingly overcome by a severe mental illness as a result of the terrible long-term overwork. His behaviour occasionally becomes eccentric and difficult to explain.

On the other hand, he gradually immerses himself deeper and deeper in the mysticism that seemed unavoidable in St. Petersburg at that time, which was, in Čiurlionis’ words, constantly oppressed by the ‘granite sky’ – that is to say, the gloomy twilight, darkness and humidity, which undoubtedly have a disastrous effect.

Regrettably, there is no information which enables us to explain specifically the apparent communion of Čiurlionis’ late paintings with the esoteric world of St. Petersburg: one can only speculate about such contacts. The city was one of the most important centres of esotericists at that time, where they pursued their various practices and expounded their teachings. Many artists were eager to participate in these ceremonies, trying out what they might have heard only in exotic stories.

GRAPHIC FIGURES

Čiurlionis’ movements gradually slow down, sometimes becoming somnambulistic, as if he felt himself to be a dancer fantasising about strange ballet scenes. The composer and conductor Juozas Tallat-Kelpša says: ‘Sometimes I noticed strange phenomena in his behaviour. Let’s say we are walking down the street. There is a pillar on the side of the pavement. Čiurlionis doesn’t walk past it, but in some strange way he walks around it, turns around and then, as if nothing has happened, continues walking. I pretended not to notice, but once I asked him why he was doing this – what does it mean? He replied that this way you can make very beautiful graphic figures.’

To Tallat-Kelpša, this seems to be a sign of impending illness. But is that necessarily the case? What if it’s some kind of geometry of paintings he is planning, or just some unspecific ideas that are teeming in his mind, which cannot be captured in any other way?

Hints of illness can be found in Čiurlionis’ letters to Sofija. Admittedly, there they appear as more general reflections on life and death by a Romantic personality.

‘Is it true that excessive sensitivity and timidity foreshadow an inevitable, sudden death? And I want so badly to live – to live with you.’ ‘I was thinking about you, and the sky was clear, but then there was a cloud, and then another, and then many, and more, and so on. Bad? No, but something like that. It will pass, just don’t blame me for it. You don’t know and have no idea how much evil is in me, it walks beside me and leaves a big shadow behind it. I get along with it and have listened to its advice many times, that shadow of mine, and if it were not for my star, which always guides me, I would have lost my way long ago. For some time now I have been afraid of that shadow of mine, it is growing too big, and I know that the shadows grow bigger as the sun goes down – I am afraid of the sunset.’

However, when Sofija arrives at the end of December 1909, she finds Čiurlionis in a completely hopeless state. After a visit to a renowned psychiatrist, Čiurlionis is taken away from St. Petersburg and never comes back. He is nursed for some time in his family home in FRAGMENTS OF ČIURLIONIS 86 Druskininkai, then transferred to a hospital in the suburbs of Warsaw. There, after catching a cold during a walk, he soon dies.

About a year after his death, a posthumous exhibition with a concert is held in St Petersburg in 1912. While he was alive, he could only have dreamed of this. Around 200 of his paintings are on display, and his symphonic poem ‘In the Forest’ and several other compositions are performed. Serious articles and the first monograph soon appear.

Who knows – if Čiurlionis had written virtuoso music or composed operas or theosophical oratorios – as many of his peers did in St. Petersburg and beyond – it would have been much easier for him to fit in and become part of the city’s musical life. It is impossible to speculate because everything was determined by his illness.

It remains to observe that Čiurlionis oriented himself definitively to the environment and medium of a great megalopolis saturated with culture and ideas, with which he felt he had a great deal in common and to which he had something to say. It was there that he felt much more at home than anywhere else, even if he was almost unnoticed. In that Russian Tower of Babel, where you could hear countless languages.

These things should not be confused with Čiurlionis’ beautiful gestures to the fragile Lithuanian culture of the beginning of the century. They should probably be valued as noble selfless acts, matters of faith and duty, without really expecting any reciprocal response. For such a response to be heard, much more time had to pass, much more than Čiurlionis was destined to live.

A SENSITIVE MELODY

It took many years for Čiurlionis to become a celebrity. Undoubtedly, exalted and mythologised, which Čiurlionis certainly deserved. First of all, as an original visionary painter. Čiurlionis is now the most important face of Lithuanian art, and it is unlikely that any other Lithuanian will equal him for a good 100 years.

As a composer, however, Čiurlionis remains in a rather uncomfortable shadow, as if he has not found a more solid place in history. Pianists are playing the young, the youngest, one could say the ‘green’ Čiurlionis, the work that he wrote when he was studying at the Warsaw School of Music and which reflects the end of the nineteenth century. Unfortunately, they almost persist in avoiding his later, in its own way experimental, music, which emerged after Čiurlionis began to paint, and which is convincingly set in the twentieth century. Even his great Romantic symphonic works – ‘In the Forest’ and ‘The Sea’ – appear mainly on anniversaries and holidays. Perhaps this is the price and the unenviable fate of art which is identified with the nation?

‘And a sensitive melody floats, and leans against the green forest – and the grey sky. It floats untaught by anyone, straight from the heart, and awakens some strange longing, it reminds us of something eternal. Go and listen to it’, Čiurlionis suggested in 1909. It is good that people are now listening attentively to the silent music of his painting.

M. K. Čiurlionis, Rex , 1909, tempera on canvas

Šarūnas Nakas is a composer, essayist, radio broadcaster, and curator. From 1982 to 2000, he directed and conducted the Vilnius New Music Ensemble, which he founded. With the ensemble, he toured 16 countries, performing works by Lithuanian composers written especially for the group. He has worked as an editor for the music sections of various cultural publications and has written around 100 articles. In 2001, he published the textbook Contemporary Music, which explores twentieth-century music and its most prominent composers. Since 2002, he has produced radio-essay programmes on contemporary music and the history of Lithuanian music. He curated the music section of the international art exhibition ‘Dialogues of Colour and Sound. Works by M. K. Čiurlionis and his Contemporaries’ (2009) and organised the exhibition ‘Juzeliūnas’ Cabinet: Modernising Lithuanity’ (2016), both at the National Gallery of Art, Vilnius. In 2007, he was awarded the Lithuanian National Prize for Culture and Art. He is currently working on a book about M. K. Čiurlionis.