A Forest is Like a City – With its own Streets, Squares and Different Land Uses

In 2020, we joined a hike along the Skroblus River organised by Verpėjos (The Spinners); an artistic initiative, assembled by artist Laura Garbštienė to research and discuss rural traditional lifestyle and nature preservation on a local and global scale. Among the participating artists and scholars, we met biologist Onutė Grigaitė. As we hiked, we talked about Laura and Onutė’s unique motivations and how they live, study, and create in these actively deforested woods. Over several days, we followed the course of the Skroblus, a small river that begins in groundwater sources in Margionys and flows along deep fracture lines in the crystalline basin, winding through sand dunes overgrown with pine forests.

Laura moved to the village of Šklėriai, in the southern Lithuanian region of Dzūkija, to rethink her approach to art and her understanding of what constitutes a work of art. Living among the forests, she discovered forgotten practices related to agroforestry, sheep grazing, spinning, and plant-derived dyes, and created her own unique relationship to her environment.

After becoming a biologist, Onutė returned to her home village of Musteika, situated near the Čepkeliai mire, and began to study an environment she already knew quite well, discovering new species in the process. Able to identify plants and ecosystems by name, she defends the chance to be in nature without severe restrictions, feeling a sense of responsibility through greater awareness.

In the following interview, which we conducted by email over the winter of 2020 and 2021 during the Covid-19 pandemic, we asked Laura and Onutė about their unique inner and personal motivations and their life among the marshes and sandy forests of Dzūkija, where trees are being cleared and environmental regimes are changing.

Jurga Daubaraitė and Jonas Žukauskas:

Onutė and Laura, how do you use, impact, and see the forest, since both of you live and work there?

Laura Garbštienė:

When I’m in the woods I feel like I’m in outer space, in a safe embrace, but in a boundless expanse at the same time, one that is impossible to comprehend. Here are just a few examples:

Losing a knitting needle

I take my sheep into the forest every day, and they lead me further in. My house is in the woods, and the woods are in a village. One September, as the boletus mushrooms had begun to sprout everywhere, I was walking behind the sheep, following where they’d lead me. I left them in a neighbour’s field with newly growing trees, and I walked off a few metres away into a pine grove. I had four knitting needles in my right hand with a black sock I’d started, and a fifth needle in my left hand. I was studying one of the boletus and searching around it for smaller ones peeking out through the forest floor, when I heard my dog barking and saw the sheep run off. I ran after them across the small grove and found them all calmly together, while my dog was off in the distance, testing the trajectories of the other forest inhabitants with an occasional bark. I continued my knitting, but the fifth needle was no longer in my left hand. I tried to go back to the boletus I’d found, but all the pine needles and twigs had swallowed up my knitting needle, my footprints, and the precise way back to where I’d been. My feet tread on a motley, multi-coloured carpet. Sometimes I wonder if my needle got stuck in the wool of my oldest sheep – the very sheep I didn’t find time to shear in the autumn.

Losing a lamb

Another September, my small black sheep gave birth to a weak little lamb. I was taking the flock out to the woods and the lamb, left at home, began to bleat and asked to come along. The second day we all went out together, but the lamb would easily tire and would lie down to rest, and as the flock moved on her sheep would cry out. So, I’d pick up the lamb and encourage the mother to hurry along and find the others. The sheep usually followed the same path, finding new little areas each day. The mother grumbled as she followed behind me, asking for her baby back. So, I’d put him down and, after taking a few steps together with us, the lamb would once again get tangled up in the bushes and piles of branches. The forest was very tasty, because it had been recently cleared. There were all sorts of sprouting black alder, willow, and aspen cuttings as well as cut tree branches that were already dry and therefore less tasty. They hadn’t decomposed yet and were strewn about everywhere, making it difficult to walk through the forest. The lamb grew slowly, but within a week he was stronger and was able to keep up with the others. One evening we stayed out longer, a bit further away – it was growing dark, and the sheep were still far from home. We got home just before dark. In the yard, the mother sheep noticed that her lamb was missing. I went out with a torch to find it, and I ran around in frightened circles, stopping now and then to listen. Sheep usually go quiet if they sense danger, especially in the dark. I listened again and made a few more circles until I finally heard a frail, childlike voice. The lamb was very close by, tangled up in a pile of branches. He had recognised me!

Onutė Grigaitė:

Today, I saw a migratory crane for the first time, and the emerging ants, too. The crane walked through the field all alone, carefully scouting out the few bare patches of ground that had emerged in the melting snow. I wondered what it might find there. I walked over and suddenly I understood: the old grass was studded with vole burrows. Clearly the crane was hunting here, since the bogs were still covered with snow. I got embarrassed that, until then, I’d never known what cranes look for in the fields, and that I’d brought halffrozen apples with me, hoping to feed them…

The guard ants had emerged into the world from the anthill to make ventilation holes. I was looking for living ants, because according to the old custom and belief, if you see an ant before you see a frog in the spring, you’ll be as quick as an ant… So, I saw the ant and brought home the wonderful news to my 88-year-old mother.

As I walked and waded through it, I thought about what the forest meant to me. Calling it a second home would seem both too banal and insufficient. As I live my life, I can always build and create a home – but I can’t do the same with a forest. I often say that humans are part of nature, but even that is somehow shallow and doesn’t reflect reality.

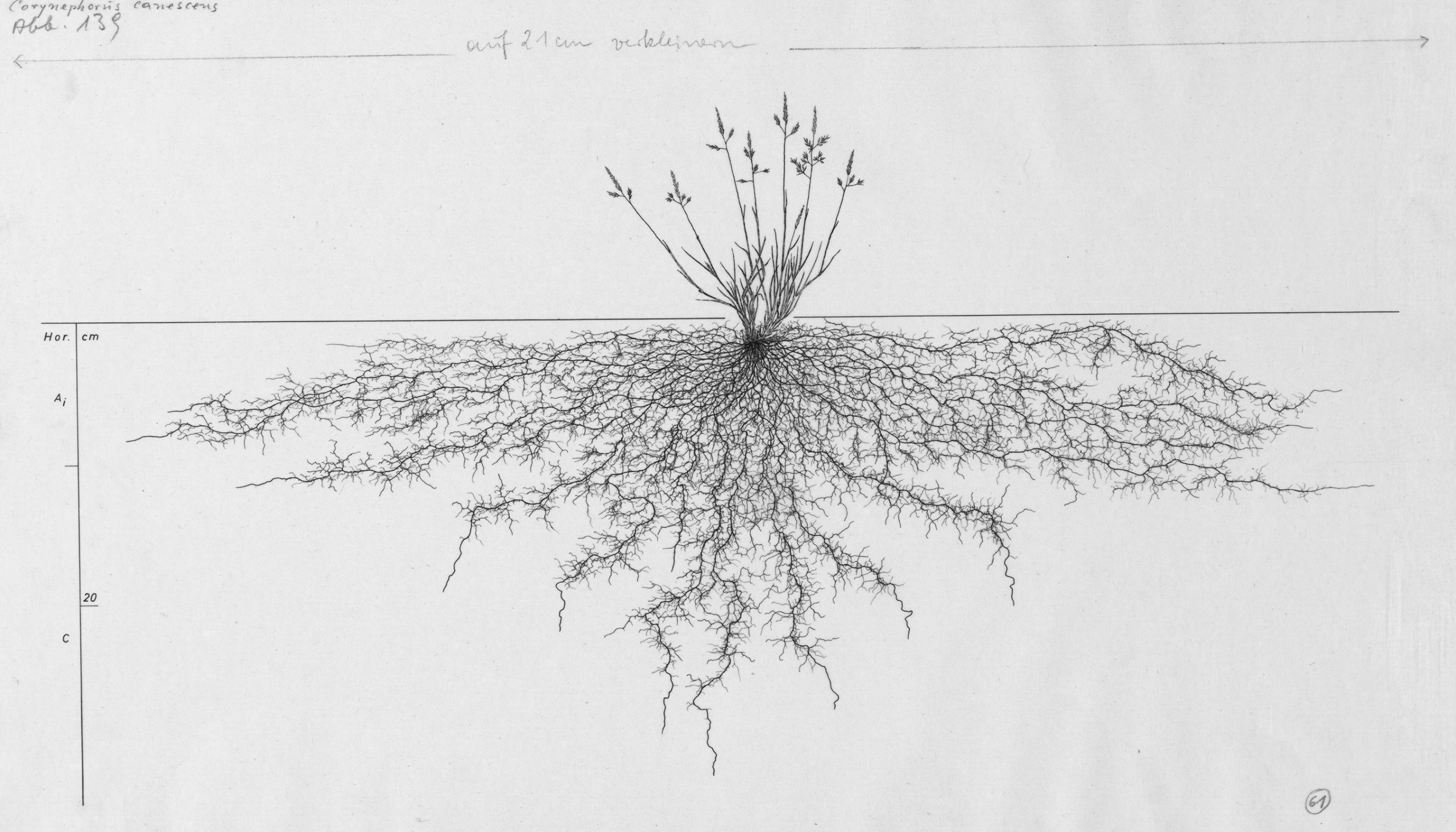

An image came to mind: I’m like a plant, let’s say a bunch of grey hair grass, and my roots and their root hairs are the interfaces, connections, and synapses connecting me to the forest.

Through all of my senses and vital functions, especially breathing, those bonds reach into every one of my cells. And I name them like a child would: I breathe the oxygen made by the trees, my immunity is protected by the phytoncides from the pine groves, the forest provides me fully-fledged nutrition from the berries, mushrooms, and animals, as well as wood for my home and furniture, it protects me from floods and droughts, brings me sweets made by bees, and heals me with medicinal herbs and twigs. And thousands more yet undiscovered and unnamed but living and functioning reactions connect me to the forest. And if we talk about lifestyle, then mine, as a child of Dzūkija’s woods, is shaped by my experiences in the forest.

I might be wrong, but I’m going to be so bold as to compare life in the city with life among forests. I imagine that a human in the city is like a stone or a brick that interacts with his or her environment solely on the surface of that brick or stone. But a human interacting with the forest, as I said earlier, is like a plant with thousands of tiny roots, through which communication goes both ways.

It pains me to think about the cleared forests, where the trees ‘die’ like people in a war. But I also ache for those reserve-protected forests, where no human is allowed to set foot, and where any of the signs of their harmonious coexistence is wiped out. Because we’re naturally encoded with the imperative to be in contact with nature, I believe that, once we recover from this chronic stroke, we’ll learn how to rediscover and build that connection with nature, with the forests, and with our environment, as part of our own roots.

JŽ:

I keep remembering how Laura and I drove around the area, along the Čepkeliai mire to Musteika, through the Vazdeliai Forest, where there are so many fields of cleared trees. I remember thinking about how I could look into the future, to watch the plants grow over many years in those clear-cut spaces, and how their interrelationships might recover. But do forests recover? After all, there are thousands of species working together along interrelated cycles; the time needed to grow a forest and recreate these connections is unfathomable for a human – you need to have a grasp of so many concepts and such complex knowledge to understand it all. Where we are now, on the Curonian Spit, the Pinus mugo (or mountain pines) being clear-cut were planted on drifting sand dunes more than one hundred years ago. When the mountain pines are completely cleared, they’re naturally be replaced by deciduous birch trees that prefer the new combination of a warming climate and the soils created by the mountain pines. When the forest changes this way, we lose our trails and the familiar species whose names we know…

Laura, you were telling us recently about some aspens near you that were cut down for no reason, and whose wood no one eventually purchased. How do we rediscover our trails and the familiar trees and plants in cleared and reviving forests?

LG:

Every year, I can’t wait for the puddles and snowdrifts to dry up so we can go into the woods!

Jonas, I can relate to your desire to study everything and learn how things renew and how they’re interconnected. When I moved to the village, I created a short book called Kaip pasėti mišką (How to Plant a Forest). It was a set of instructions about how and when to collect tree seeds, how to germinate them, how long to keep them cold or warm, etc.

I brought back a decaying fruit, full of germinated seeds, that I had found under a quince tree in the spring at the botanical garden in Kaliningrad. I also brought back a branch from a flowering blackberry plant, from which I’ve grown an entire hedge. Bladdersenna seedlings can thrive, but they’re eaten away in the winter by rabbits; they apparently find them tastier than their relative, the common broom shrub, which grows naturally in these parts. The bladder-senna has very impressive roots – they grow like rope in the sand dunes near me, several meters into the ground.

After a while, I lost the urge to systematise everything and follow all of the cycles. I started to get to know everything through the experience of being. The longer I lived in that place, the more I have become one of the many elements of recovery in that cleared plot of forest. I have a hard time seeing the broader picture, because I’m in a very small fragment of time and space.

On the other hand, I want to have a dialogue and collaboration with professional researchers, which interests me not so much for the opportunity to share and spread information, but for the chance to create new meanings. As artists, researchers, or environmentalists, we work in different worlds, and if we venture into a foreign field, our work sometimes appears amateurish and therefore insufficient – which is what may have happened with Kaip pasėti mišką (How to Plant a Forest). The aspen trees were very thick and were cut in early spring. The bark peeled off easily from the trees, but I didn’t peel them because I couldn’t lift them. I wanted to strip them and make sashes and weave a carpet. Their bark has a beautiful surface. But they began to go bad and smell, and no one bought the wood until the summer, which is when a biofuel truck came and ground them up. I wanted to take that cubic metre of aspen wood and make all sorts of things from it, increasing its value a thousand times. But if it had been my cubic metre, of course, it would have been thriving and green to this day.

JD:

What about the clear-cut fields – do you visit them, and do the sheep find anything to eat among the stumps? What’s the grazing range of your sheep – where do you go with your flock?

LG:

I think about the sheep a lot. They’ll indicate whether they prefer the pine or the birch grove. But I’ve noticed that the places I like are also more suited to the sheep places where there’s more of everything – more old trees, hollows, creek banks, and shrubbery. They don’t want to get overheated in an open field in the summertime… Sheep probably aren’t true landscape managers – they lead you to the best place and they support that place, but they don’t essentially alter it.

Sometimes they won’t go to a spot, even though it seems to have things to eat. Last year there was a spot with good grass growing, a narrow strip of field between small and dense deciduous forests – between walls of green. I tried to nudge the sheep there several times, but they wouldn’t go. I think that may have been a deer spot – I’d sometimes see them there in the early morning.

If not for the increasing size of my sheep’s nursery school, I would never know it’s already spring – I can truly say I’ve lost track of time. I’ve heard that villagers would sit down to weave in March. They’d spin a supply of thread over the winter and load up their looms. I got this loom from the village of Margionys already disassembled, but with a design and fabric already started. I was able to put it all together and the pattern stayed the same as that of the unknown weaver from Margionys who had started it. Now I’m weaving it with my own thread.

JD:

This fabric looks like a Dzūkija chessboard, and the pattern is like a forest with a new owner. Can you tell us more about the routine of spinning thread that takes up more than just your wintertime? How did you establish the Verpėjos (The Spinners) artist initiative – what drove you and what were you hoping to find?

LG:

The fabric really is like a chessboard, but I don’t find the military association very appealing. Patterns have names, and this one is called Žvaigždutės (little stars). But it’s very similar to abstract, even op art. I think that the art of Dzūkija’s women has endured the longest as a continuing activity, because all of them knew how to weave. Some of the fabrics have a real ethereal effect, because they’re woven in shiny thread that catches the light. If you stare longer into that shimmering, it’s almost like you’re being pulled into another world. I myself only began weaving this year.

I learned to spin wool after I sheared my first three sheep. I wanted to respond to the prevailing view these days that spinning is nothing more than a demonstration of a vanished craft. I wanted to use spinning as a medium to hold a discussion about the cultural and social changes happening here, in a peripheral area, and invite artists and local people of different generations to come and spin together. That’s how Verpėjos came about – the first event of its kind to be both an exploration of art and a workshop for spinning wool. We visited women living deep in the forest, hoping to find those who still spun. Many said they’d only spun thread in their youth, but that they continued to weave all their lives, only with synthetic factory-made yarn. Very often, their guest rooms would be sparkling with woven bedspreads and curtains, all of it coming together into one single composition.

Gradually, the name Verpėjos took on a new symbolic meaning and began to include more people and different activities. We opened a gallery at the train station in Marcinkonys, we hold art exhibitions, but we still run into obstacles for the Verpėjos art residency.

For me, however, spinning is also a daily activity, a ritual. The Verpėjos orchestra project was conceived to invite people from different locations each time to come and spin together, followed by a performance as a ritual initiation into the community of spinners. Spending a long time together spinning, in silence and listening to the sound of each other’s spinning gestures, is an activity that brings together people of different generations and experiences.

JŽ:

Laura, we love your Skudde breed of sheep and we look forward to seeing them at the Neringa Forest Architecture residency at the Nida Art Colony (NAC). They’ll graze there just like they do with you in Dzūkija, led by a shepherd around the forest and open areas, creating the opportunity to see the landscape by following them in their path.

In my mind, I keep seeing the hanks of yarn you’ve spun from your own sheep’s wool – they seem to be images of your daily walks through nature. What kind of spectrum of colours do you find in the woods?

LG:

I collect forest plants and extract dyes from them. I especially like to pick up parts of plants that are already lying about on the ground. For example, I peel buckthorn, willow, and alder bark from cut branches. There’s always a lot of them left on the forest floor, even after the branches have been collected and ground up for biofuel. I also like cemetery flowers like marigolds, from the village cemetery after the first autumn frosts. They’re already drooping, and some are still planted while others have already been plicked – I find those outside the fence. I’d also once planted some woad flowers in my garden and they grow on their own now, delighting me with wonderful clouds of yellow when they bloom. They thrive here like flowers and could easily move on into the fields if there were any nearby, since they’re very prolific. But I’m surrounded by forest, so they stay put. It’s a biennial plant and seeds itself in the best spots in the garden. I like to concentrate bold colours in one place in my wool, even though sources of vivid pigments in nature are rather limited. That’s why you can only take small, concentrated amounts of them. There’s probably never too much of anything in nature, and I’m careful what I take. And I wouldn’t physically be able to take any more. It’s wonderful when you see a colour that isn’t usually visible. I can’t get much of a red pigment, but if there’s a rainy autumn, I can sometimes find red-gilled webcap mushrooms. Actually, I was very lucky last November and picked a lot of them in the pine forests on the coast of Nida. All sorts of processes occur during dying – fermentation, reduction, and some that are almost comparable to the way milk transforms into yogurt, for example – but it’s also a kind of laboratory process.

JD:

Onutė, you mention ‘disappearing signs of coexistence’, and that you’re pained by cleared forests and the impenetrable reserve areas that are off limits. What kind of new relationship with forests do you imagine? What would be worth changing now and in the more distant future?

Are drawings of plants or lichen part of your academic work? How do you use the drawings and notes in your work, do they become continuing ideas over many years?

OG:

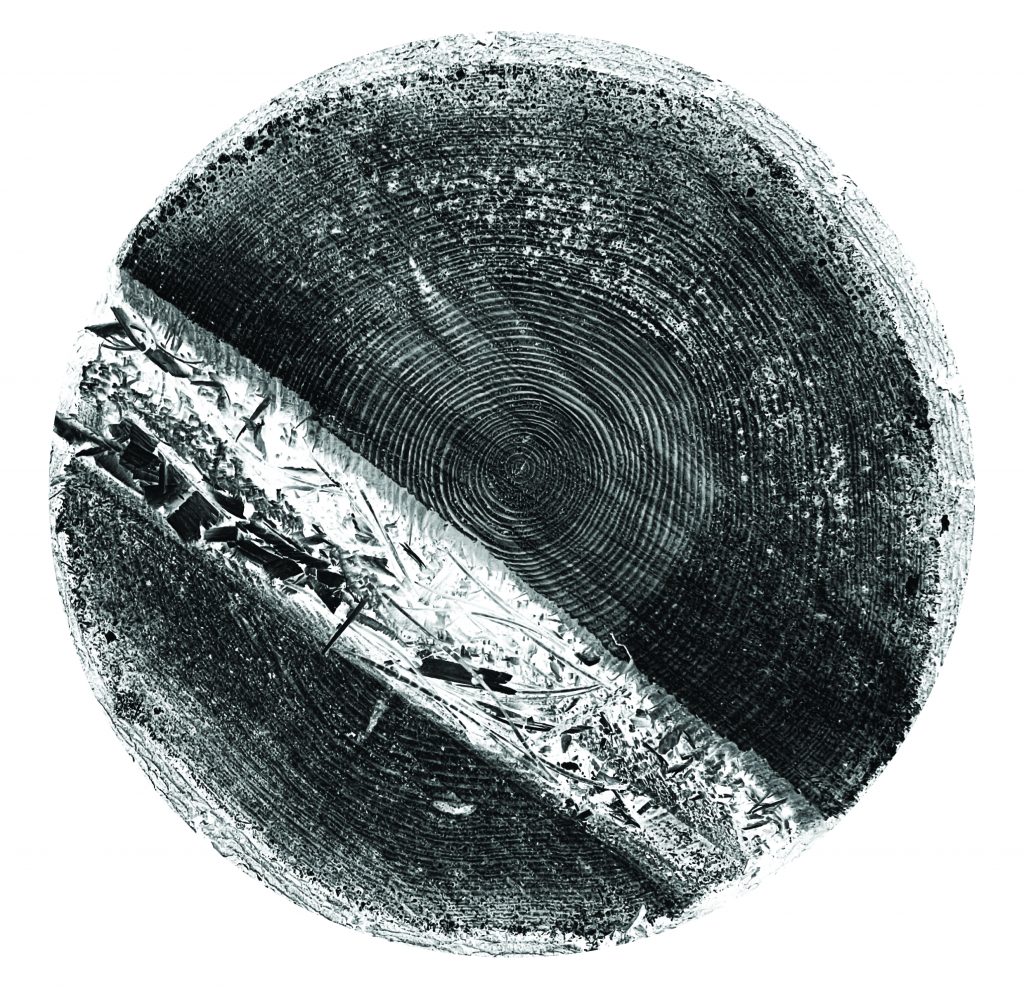

I’m glad that you forced me to search through my old papers for root drawings that I made between 1984 and 1985, when I was preparing my dissertation. I was comparing the roots of land-grown plants with those growing in marshes. I was able to find some – I had to press a few drawings to even out the wrinkles.

It’s a schematic that I redrew: roots from small pine trees growing among bog woodland with Labrador tea and dryer lichen pine forests (kerpšilis); and a stem from a bog blueberry growing in a bog. It was nothing special, but I still remember the feeling of digging around in the sand or the peat moss and realising the endless diversity that exists in the roots we don’t readily see…And how they, like some sentient beings, arrange themselves to ensure that their plants thrive and blossom.

As I looked through my things, I found drawings and schematics of wild bee nests by my colleague, the late Dr. Virgilijus Monsevičius. Virgilijus was a European-class specialist in wild bees. He inventoried as many as 324 bee species in Lithuania. Some of them live in the ground and two nests have been recorded in these drawings. The architecture of both roots and ground nests is meant to ensure a good life.

It hurts to see the forest being cleared so widely and disrespectfully. I’m not against growing parts of forests for harvesting, but I dream of a way of clearing that would protect some of the trees and not harm or hamper them. Yesterday an elderly man from the village told me how they used to cut birch trees 40 to 50 years ago and carry them by hand or pull them on a sled, making sure not to graze or scrape the bark on an adjacent fir tree. But nowadays they come with combines, even when they’re just doing maintenance or thinning work…

It’s painful, because I believe there’s an existential bond between humans and trees. Yesterday, that 82-year-old man said to me: ‘Do you see how many broken trees there are? Old people used to say: “That’s a sign of how many people will be broken or depart this world…”’

In my childhood, when all three generations would gather together, our conversations in the evenings would revolve around what we’d seen in the woods, what paths we’d walked, where we’d picked berries, where the animals grazed, where we’d seen a moose, etc. And how many wonderful names there are! For paths, woods, glades, meadows, pine trees… A forest is like a city with its own streets, squares, and different land uses. Now, we might even compare a ravaged forest to a demolished city.

People used to herd animals, pick berries, hide, and hunt in areas that are now declared reserves. We’ve completely pushed people out, so paths are now overgrown, fields are open, many plants have disappeared, old roads have become overgrown, and we’ve lost open habitats and many rare species along with them. We’ve become so deprived. And we’re not even thinking about how to return people to that harmonious coexistence – quite the opposite. For example, in the Čepkeliai Strict Nature Reserve they plan to reduce or even entirely stop issuing permits for local residents to pick cranberries. I dream of working with local residents and visitors to find ways to revive pathways, roads, and glades through volunteer initiatives, reporting, research, and specialised hikes. I think that most people don’t even know what a natural forest is, because they’ve never seen or experienced one. And I don’t really have anything to offer them, since we’re not allowed to visit the reserve. That relationship with the forest has to be an equal one, established as one would with another being, not a raw material.

They’re trying to ‘reconcile the insatiable forestry industry’ and the naturalists. The imposed point of reference consists of the threat of EU sanctions and the suspension of funding for structural projects so long as Natura 2000 areas aren’t protected according to commitments undertaken upon admission to the EU – a delay of 12 years already… I’m concerned that there’s no discussion whatsoever about ecosystemic forest services. Or, for example the proposal that has been made to cut out a glade to create more of a mosaic pattern, but when they remove those trees, they’re also removing the nutrition for creatures of the forest floor, such as bacteria, etc., that feed the forest by decomposing organic matter, and so many other as yet unknown interrelationships with other species.

What needs to change, first of all, is our way of thinking, and the starting position for a dialogue. In my mind, society has to receive comprehensive information. What is a forest and what is our real situation – who’s going to tell us this? The timber magnates will do that by representing their own interests, they have the money for that. But how much will the public organisations be able to say without funding and without a serious scientific foundation and estimates about the natural economy? I hope that artists might be able to build some bridges in this regard…

JŽ:

Onutė, you’re driven by an inner motivation to study and understand how your natural surroundings work. What compelled you to become a scientist?

I ask because I’d like to understand how this motivation is passed on, and how we might think about fostering a relationship with our environment in the future. It seems to me that, outside of high politics, an inner human drive can create the opportunity to change our estrangement from natural systems and change our perception of forests as nothing but a material resource. What do you think?

OG:

The fact that I am what I am now is no great accomplishment of my own – I was simply guided by my inner voice, the advice of others, and fortunate circumstances. I never thought about working as a scientist – I didn’t even know what that was.

I finished first grade in a building in which the first Lithuanian language school in Musteika was opened in 1918 by the young couple Tadas and Honorata Ivanauskas¹. Their own sense of patriotism brought them back to Lithuania from St. Petersburg, Russia after the revolution, to teach at a forest village school. Since Professor Ivanauskas later visited the school every year, I seem to remember running down the village road in 1969 to greet him. Much later, I learned that he would bring or send his own books for us to read. But I had considerable difficulty reading in those early classes, so I didn’t read those books or have any interest in them. In the village, we played with nature – chasing butterflies and dragonflies, waging war with pine cones, swinging from pine tree branches, tasting shoots and gooseberry bushes – this is how we learned about nature, apparently… Because naturalists were always following Ivanauskas’ trodden paths and finding their way to our village, one of them once spent the night on the hay in our barn, and around 1975 he gave us a copy of Ivanauskas’ Gamtininko užrašai (A Naturalist’s Notes). I ‘consumed’ that book and was surprised to see how much he’d written and in such a unique way about places that I knew so well. I also read a copy of the magazine Mūsų gamta (Our Nature) that the pastor had given me.

I chose biology because I absolutely wanted to live in the village among the forests. When the Čepkeliai Reserve was established in 1975, I dreamed of returning to familiar places and working there. At the university, I said that if I couldn’t go to work studying the Čepkeliai mire, I would go to Belarus and teach at schools in the Lithuanian communities there. I got the chance to work in Čepkeliai thanks to a miracle and many tears. I’ve always been drawn to the marsh wetlands – of all the biomes, to me they are the most beautiful, lovely, and familiar. After that, the Botanical Institute was working on a monograph about Lithuanian flora, so they needed someone to study high marshes. I finished my dissertation, but after that I didn’t really want to leave my native Musteika village or Čepkeliai mire to work at the institute, so I didn’t continue my work as a research scientist…

Whenever I see children in the village or in the marshland, I always think that those veins that carry the water of life – which we share with our environment – are a part of our nature, both on a physical and a spiritual level. It’s important that those veins do not become blocked or too narrow. Or, what about the sensitivity towards nature felt by artists who’ve grown up in the city. Where does that come from?

As I’ve been thinking, I recall something that Professor Ivanauskas once said: ‘We can’t solve anything with laws if people aren’t taught to love nature from childhood.’

I still hope that future generations will consciously reduce their material demands at nature’s expense and will find more of themselves in nature and more of nature within themselves, and a more fulfilling life at the same time.

After all, that’s why we work together, each in our own way – which is good for us, is it not?

Jurga Daubaraitė and Jonas Žukauskas, are a duo of spatial practitioners currently based in Vilnius. Through architectural, curatorial and research projects they aim to create new relations between societies and their environment, past and future, by seeking to rearticulate architecture across a wider ecology of practices. They curated the exhibition ‘The Baltic Material Assemblies’ at the AA Gallery and RIBA in London (2018), and were co-curators of The Baltic Pavilion at the 15th International Architecture Exhibition at the Venice Biennale (2016), and co-editors of The Baltic Atlas published by Sternberg (2016). Among other projects Daubaraitė and Žukauskas are currently working on the Creative Playground and Garden in Vilnius. Together with Egija Inzule, as well as working together on the new publishing initiative Kirvarpa, they initiated Neringa Forest Architecture at Nida Art Colony in 2019, as a research and residency programme based on spatial and material processes. The programme that investigates the Curonian Spit as a case study in the context of the Balticand Scandinavian forests, considering it as an entanglement of ecologies, representations, and both colonial and industrial narratives.

- Honorata Paškauskaitė-Ivanauskienė was an educator and Prof. Tadas Ivanauskas was a zoologist and biologist and a leading scientist in interwar Lithuania and, later, during the Soviet occupation.