Songs From the Compost: Notes on Symbiotic Relationality and Eglė Budvytytė’s Lichenous Poetics

The word lichen has speculated roots in the Proto-Indo-European leigh, meaning ‘to lick’. Perhaps because of the way it grows over tree and stone surfaces, reaching out and latching on like a many-tongued sprawl.

If you were in New Zealand in 2019, there’s a chance you saw adult humans lying down on the pavement licking lichen. It was a trend. They weren’t studying etymology; they were trying to access the reported Viagra-like properties of a particular sort of lichen, which is known scientifically as xanthoparmelia scabrosa, and which grows abundantly on asphalt pavement in parts of New Zealand. Locals would complain that the lichen caused slipperiness on the roads during wet weather. Then rumours about the lichen’s aphrodisiac powers started circulating, and media outlets picked up on its more affectionate, unofficial name, ‘sexy pavement lichen’.

Like most lichen, sexy pavement lichen is very difficult to scrape off, so it invites people to go down on it, to get onto the ground with it and put their faces up amongst it and lick the same surface that it licks. The only problem: xanthoparmelia scabrosa also carries potentially toxic levels of heavy metals. Copper, lead, zinc – essential components of our partly mineral bodies, but poisonous in excess.

So lichenologists were worried about the humans on the ground. Dr Allison Knight told one local news service that while the lichen does contain a chemical that is ‘somewhat analogous to Viagra’, she did not recommend ‘going out and licking the footpath.’

The Online Etymology Dictionary, by the way, connects the word lichen with two other words: lecherous and cunnilingus. It’s a tangled root system: the lingus in cunnilingus is not just the tongue that licks, it’s also the tongue that speaks; the lingua of linguistics, lingo, language.

*

During her visits to Nida Art Colony on the Curonian Spit in 2019, Amsterdam-based Lithuanian artist Egle Budvytytė spent many hours in the surrounding forests, where the entangled forms of life and death and nonlife host incredible varieties of lichen: endlessly mottled grey-greens, powdery yellows, intricate orange lace, tendrils draped around like casually ostentatious feather boas.

Her film Songs from the Compost: Mutating Bodies, Imploding Stars, made in collaboration with Marija Olšauskaitė and Julija Steponaitytė, was shot in those lichenous forests in the summer of 2020. With a cast of teenage dancers and students from a local high-school, the film is a kind of meditation on sylvan-cyborgian symbiosis. The bodies are sites of activity, but they’re never upright; they’re pulled toward the ground and each other, moving between the trees, along the sand dunes and coastal shores, over and into the mossy forest floors.

The soundtrack is made up of a series of many-tongued songs produced by Budvytytė, where digitally processed voices bubble up and break apart – voices licking themselves, recomposing one another:

I am hatching I’m being hatched

I’m stretching time in your spine so long so long so long so long

she will take care of you, she will fuck your past

a crack in the rock, a crack in the narrative

how about decay, rotting, decomposing as technologies for non-linear time

look into my shapeless eyes

come into my kingdom, moist-wet-slipperycomplex

suck up on my wisdom, muddy-airy-trippyperplexed …

*

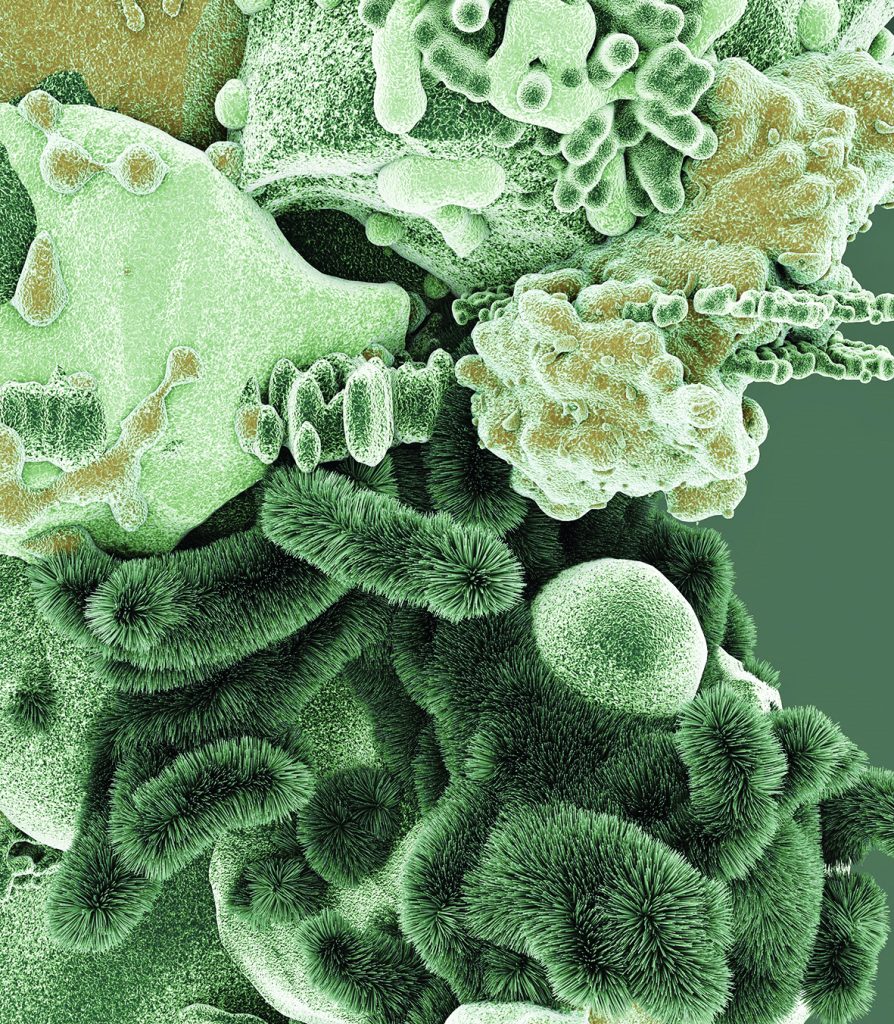

As composite organisms arising from a relationship between fungi and cyanobacteria or algae, lichens challenge traditional notions of organism and species autonomy, by straddling multiple classificatory designations.

Fungi can’t photosynthesise on their own; they propose a structure, through which their photobiont companions bring the light. But the characteristics of lichen aren’t attributable to any of their individual components. There is no simple division of labour through the allocation of predetermined tasks; this is a mode of collaboration where something happens between the contributors which never belonged to any of them.

A Swiss botanist named Simon Schwendener first proposed his hypothesis that lichens arise through the mutually beneficial cooperation of genetically separate organisms on 10 September 1867 (four days before the first publication of Volume 1 of Marx’s Capital!). It didn’t go down well. Schwendener’s ideas on the matter were vehemently rejected by the scientific community for years – and a final attempt to disprove the symbiotic (‘living together’) theory of lichen was published as late as 1953¹.

In the 1960s, when the biologist Lynn Margulis began championing the theory of ‘symbiogenesis’ – where symbiosis is the primary mechanism of evolutionary novelty and complexity – she was also widely dismissed. Her work on life’s many layers of cooperation, interdependence and co-creation would gradually become less controversial, but it posed a serious challenge to the NeoDarwinian emphasis on the competitive ‘survival of the fittest’, and the resistance she faced is telling.

Towards the end of her life, Margulis appeared in a public debate with Richard Dawkins, the Neo-Darwinist who first became famous with a book that emphasised ‘selfishness’ as a core evolutionary principle. In the audio recording of their exchange (which is included in John Feldman’s 2017 documentary Symbiotic Earth), there’s a brief moment that’s particularly illuminating:

Dawkins is responding to Margulis’s ideas, and he sounds very unhappy. ‘Take the standard story for ordinary animals,’ he implores, ‘what’s wrong with that? It’s highly plausible, it’s economical, it’s parsimonious, why on earth would you want to drag in ‘symbiogenesis’?!’ She responds by laughing and saying, gently, ‘because it’s there.’

Symbiotic relationality isn’t dragged in as an unnecessary complication of an otherwise perfectly neat (‘economical’) picture. The complexity is already there – and to knowingly exclude it would amount to an ideological distortion. (Think of the joyless desperation with which Jordan Peterson, some years back, kept trying to make lobsters prove, once and for all, that hierarchical and competitive social dominance is ahistorically ‘natural’.)

Margulis insisted that alliances between algae and fungi have been crucial not just for the existence of symbiotic organisms like lichens, but also for the development of all vegetative life: plants could not have evolved from algae in the oceans and taken root on dry land without the underground efforts of fungi, who deliver messages and nutrients to their upright photosynthesising cohabiters. The part of a tree that performs photosynthesis is illuminated as it reaches up towards the light, but this is only one feature of an expansive network of alliances. In the dark, wet and wormy underground, where roots are all tangled up with mycelial-bacterial-mineralchemical-informational transmissions, myths of heroic, entrepreneurial individualism are completely unsustainable.

*

‘In the relative: the negation of a History and the open dawn of histories, what accomplishes Time and hardens it there in the lichen of frail inspiration and the dark stubborn rust of wilful parlance, flush with the earth.’²

This is Édouard Glissant, writing in the 1960s. While science tentatively ‘discovers’ the extent of life’s relationality, the poets are of course already in its midst. ‘Let me try clumsily to draw a tree,’ Glissant writes. ‘I will reach a span of vegetation, where only the sky of the page will put an end to the indeterminate growth.’³ The tree drawn in isolated selfsufficiency would be an obfuscation of what Glissant called ‘the poetics of relation’, wherein ‘each and every identity is extended through a relationship with the Other’.⁴

Later in his life, on a visit to his native Martinique, Glissant spoke to the filmmaker Manthia Diawara about the ‘creole gardens’ that were secretly maintained by enslaved communities on Caribbean plantations (in Diawara’s 2009 film, Édouard Glissant: One World in Relation). In contrast to the coercive monoculturalism of the plantations, Glissant describes how these small, clandestine gardens were sites of diverse multiplicities:

‘They were able to grow dozens of different types of trees, different scents,’ he relates. ‘Coconuts, yams, oranges, pines, dachines, choutchines, sweet potatoes, cassava’. Cultivating these plants involved cultivating intricate knowledge about the ways in which different species can protect and nurture one another, so that the conditions for difference and mutually supportive growth could be held within a violently compressed space, as a necessary means of survival.

‘When I say: tree, and when I think of the tree,’ Glissant wrote, ‘I never feel the unique, the trunk, the mast of sap which, appended to others, will group together this stretch of forest cleaved by light.’ ⁵

Such a relational attunement does not have to mean that anything can become anything else, or that no specificity can take shape. Glissant describes the ‘span of green’ on a downhill road to the shore, where ‘No trees or outlines are discernible’ – but in the midst of it he is struck by a red flower that ‘glitters and moves immobile’.⁶ He also describes several specific plants that stand out with historical and ancestral significance in the encultured ‘natural’ landscape, but he maintains the overall effect of ‘the surge, the Whole, the boiling density’, where identities are extended – both spatially and temporally – through their relations.⁷

‘What good does it do you to know,’ Glissant asks, ‘if you are not flush with your surroundings, exceeded?’⁸

*

‘We have never been pure. We have never been clean’. These are the opening lines from Budvytyte’s Songs from the Compost: Mutating Bodies, Imploding Stars, sung as the bodies begin walking downhill through the forest towards the shore, dappled light reaching between the towering pine trees, onto the moss-cushioned earth.

The next shot pans over someone lying, still, on a lichen-mottled ground, with their back to the camera. A fungal growth is emerging out of their shoulder blades and fanning along the backs of their legs, which are exposed through partly decomposed trousers. The ground is rot and growth, hungry and inventive, reaching up and drawing this hosting body into its fold, breaking down boundaries, and recomposing forms that sprout out of its pull.

The costumes in the film were made in collaboration with the ground. During the first Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns of 2020, when Budvytytė was back in Amsterdam and production and shooting were indefinitely postponed, the artist buried some garments (and pieces of cloth that later became garments) in the garden behind her studio, inviting input from the soil and its critters. After about six weeks, the fabrics had accrued various inscriptions of decomposition, giving rise to an array of ecological archieropoieta – pictures made ‘without hands’, beyond individual human authorship.

The voices in the songs that form the film’s soundtrack are similarly unclean and composted. By singing through a vocal effects processor, Budvytytė pluralised her own voice into a cyborgian chorus, where the words are rotting, reverberating, mineralising, cracking, burrowing, swelling with microorganisms. ‘I am a host I am being hosted I am a hosthosting’ they sing, over and through one another, in shimmering planetary symbiosis. ‘Baby I’m your stone. I am not your resource’.

This text is a revised and expanded version of an earlier text by Amelia Groom, written for Egle Budvytytė’s digital artist book Songs From The Compost, published by The Baltic Notebooks of Anthony Blunt #3: http://blunt.cc/312734/ notebooks/3/songs-from-the-compost.

Amelia Groom, Amelia Groom is a Berlin-based writer and art historian. Recent texts have addressed rust, stones, pareidolia, blurs, lichen, ventriloquism, and silence. Between 2018 and 2020 she was a postdoctoral fellow as part of the interdisciplinary research project ‘environs’ at ICI Berlin Institute for Cultural Inquiry, and in 2021 and 2022 she will hold a postdoctoral research position at The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen. Her book Beverly Buchanan: Marsh Ruins was published in 2021 as part of the Afterall One Work series.

- David Griffiths, ‘Queer Theory for Lichen’, in UnderCurrents: A Journal of Critical Environmental Studies, 19, 2015, pp.36–45.

- Édouard Glissant, Poetic Intention, trans. by Nathalie Stephens with Anne Malena, Callicoon, NY, 2010, p.201.

- Ibid. p.41.

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation trans. by Betsy Wing, Ann Arbor, MI, 1997, p.11.

- Édouard Glissant, Poetic Intention, Op. Cit. p.41.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p.201.