The Grammar of Lichens

Path to Enlichenment

The concepts of signs and information, and of coding and language, are closely related to the nature of life itself. The materiality of objects informs how people explore, experience and understand their surroundings¹. The patterns of symbols and changing forms as signs by lichens demonstrate associative connections and intimate dialogues between them and the forest. Some remain abstract.

Lichens form my alphabet of design and together we recreate the grammar of forest tectonics. Stories can help you fall in love with the world and this is our mission. Technology is like a connector to the natural environment. It enables us to experience different relationships to our context, to extend our perception of reality in myriad ways². The poetics of a place becomes architectonic. I invite you to join the lichens and immerse yourself in the Enlichenment³.

Soft Infrastructures⁴

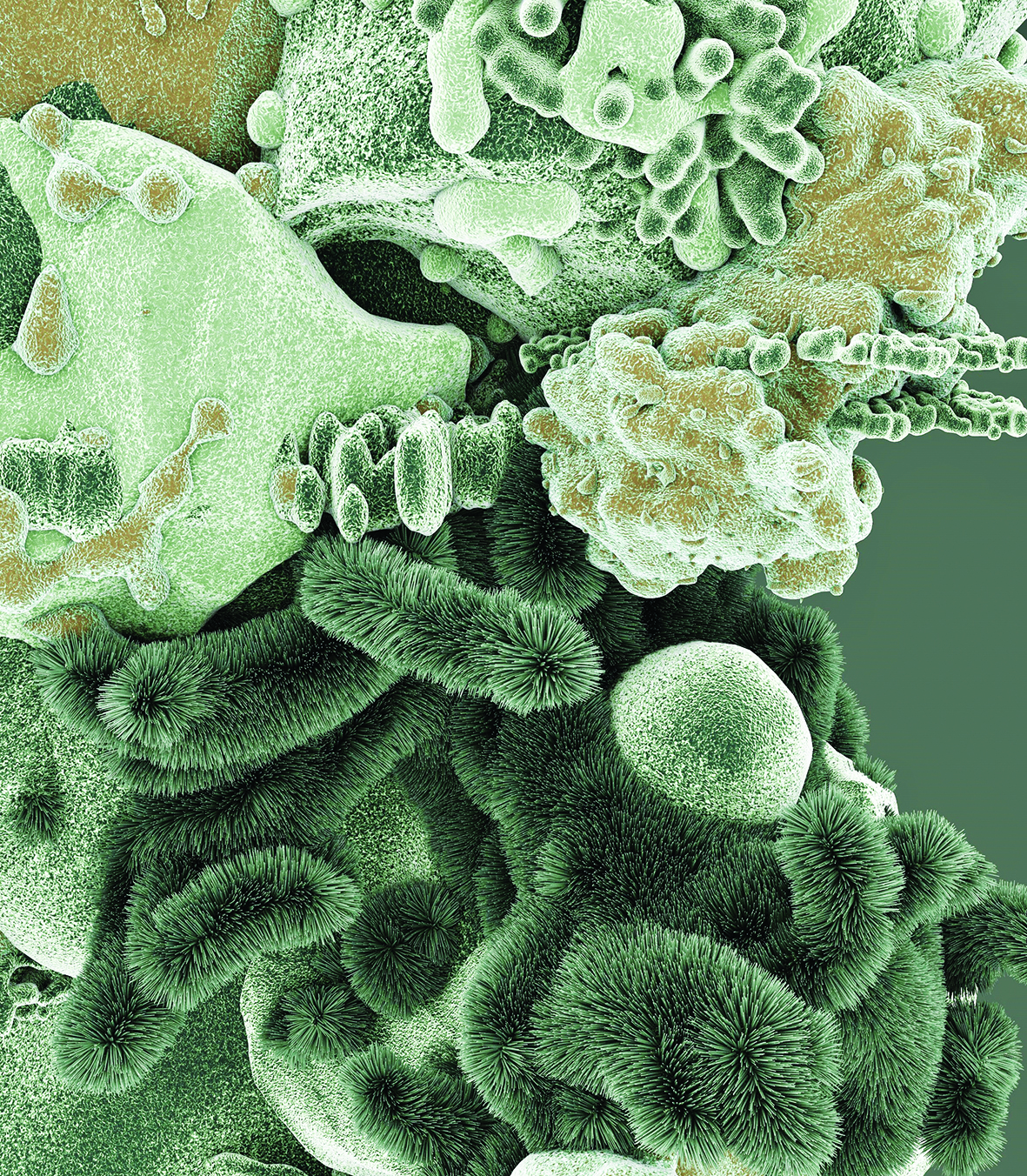

While in the forest, lichens are always soft to touch. Once you detach them from the substrate, they harden solid. They are also known as extremophile organisms – able to switch off and back on in extreme conditions and therefore inhabit various habitats across Earth.

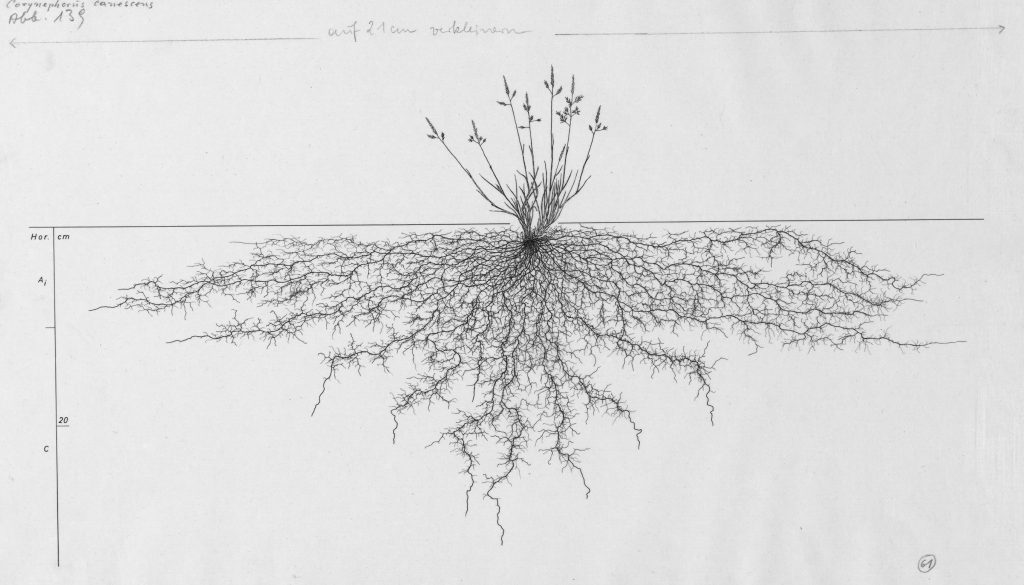

Lichens are the sensors of the environment and their hyper-articulated surfaces have intimate relationships with their surroundings, forming mutual relationships with others. They teach us how to look around rather than ahead, caring about depth rather than height⁵.

There are soft ways of reading the world; you can collect sensory experiences and follow neuro trails to join the lichens. They share the forest of softness in form, shape and size. Every nuance of lichen architecture has a word (as every feeling has a form)⁶. Their latin titles and epithets, such as lobaria pulmonaria or bryoria capillaris, illustrate their multifaceted tactilities and the sensibilities of their inhabitable context as well as their feelings towards it. By expressing their emotions to their surroundings so sensitively they are able to be diverse and distinct in their morphologies.

If you want to visualise what would happen if a building had emotions, I would invite you to observe lichens. They are the nervous system of the forest. Synapses – the elaborate membrane structures, where transmissions between nerve cells happen without touch – are the sites of change and exchange⁷. I compare the neural joints of our bodies with the lichens, as synapses of the forest. It is not necessary to touch something to be touched by it⁸. Lichens trigger my way of experiencing tectonics as the art of joining by not touching. As the hand sees, the eye-draws and the mind touches: we are able to envision our experiences in new ways⁹.

Lichens symbolise forest ornaments, the world of feeling and sympathy. They weave a living system of interwoven patterns, where inner and outer lines of growth intertwine and surfaces become architectonic parts of the matrix itself¹⁰. As the tree ring becomes bark or the soft lichen hard, I envision architecture metamorphosing to softer interpretation.

To be a Lichen

Lichens are comparable to tiny patches of emotions that are widely spread, but remain unnoticed. ‘Irregular’, ‘decentered’, ‘random’, ‘crooked’, ‘small’, and ‘glitchy’ are common cultural associations that undervalue the imperfections of these tiny creatures. In the language of design, these meanings are alike. Lichens have a very different timeline to our own and therefore the first impressions and emotional associations are of being slow, old-fashioned, outdated or even failures. Meanwhile, in the forest, while some parts succumb to decay, others are just sprouting and these are not only the articulations of life, but the source of beauty¹¹.

Biologically, lichens have so-called emergent properties, which means that even for scientists their growth, to a certain extent, continues to be unexpected and unpredictable. In addition, their mysterious ways bear fruit in polymorphic growth patterns where it is impossible to count or name the exact species¹². One might even say they share their story intuitively.

Lichens inhabit the negative spaces of imperfection as unique and fascinating systems. I believe that creativity, like the spontaneous outgrowths of Lichens, is not often linked to any kind of conscious control. By starting to unravel their rules and style, I build mine in parallel. I carefully collect their features and will use them for the overall branding (Gesamtkunstwerk) of the grammar of forest tectonics. Having courage to be bold and shy simultaneously is being a lichen to me.

I am experimenting with ambiguous and multilayered meanings, and associations of lichens, because even their biological characteristics allow them to be interpreted according to the ever-evolving conditions. In my research, lichens weave the forest tectonics, they are the symbiotic joints that interconnect the polyphonic surfaces. By reading them, I simultaneously interact with mosses, liverworts, barks, mycelium and many others (like myself). Lichen architecture is the forest to me.

To Follow the Lichen

By following these intuitive sideway paths simultaneously, without even noticing, I started building my creative practice. After my walks I always had plenty of dried lichens at home and it inspired me to document and imitate, play, and deconstruct that emotion in three dimensional space. As an architect, the most natural way for me to express my thoughts is through design. I started learning how to model, sculpt, and draw organic, complex forms and intricate patterns in the digital realm. It felt like opening a new door to understanding everything.

Having this parallel micro-cosmos on my screen, on my mind, and in my hands tackled a new beginning. Lichens – like the chameleon or octopus – amazed me with their incredible diversity in form and shape and sparked my curiosity. They became my personal thing, time for myself, searching for unexpected and scattered manifestations of beauty. You don’t question your feelings when you are in love, you just love.

Aistė Ambrazevičiūtė, a digital artist and experimental architect based in Lithuania. Her work focuses on the decorative arts of architectonics, where she celebrates and employs the forms, shapes and textures found in the intricate and complex nature of things. The goal of her practice is to stimulate the art of noticing and visualising unimagined reality. She is a creator of Plantasia Lab, where she designs digital plants using the intuitive imagination of technology. Currently she is a PhD-in practice candidate at the Vilnius Academy of Arts working on the grammar of forest tectonics by lichens. In 2021, Aistė was a resident of the Neringa Forest Architecture programme at Nida Art Colony (NAC) of Vilnius Academy of Arts.

- Seetal Solanki, Live Serpentine Galleries talk: Re-learning Perspectives, 26 June 2020.

- Serpentine Podcast, ‘Back to Earth: Systems and Sprouts’, interview with Jakob Kudsk Steensen, 9 July 2020.

- Enlichenment as referred to on the website: https://www.waysofenlichenment.net/, and highlighted in Merlin Scheldrake, Entangled Life, How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures, Vintage Publishing, 2020.

- Soft- infrastructures are described as softer, tighter and looser textures of our society. If hard structure is the relationship between all the activities that enhance the organization to complete its functions, soft structure is the relationship among all the factors which takes into account the pursuit of people’s interests to support the hard structure functions. The project imagines soft- infrastructures as the transitional nodes between various scenarios. Newsletter project The Bliss of Spam, September 2020.

- Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World, On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins Princeton University Press, NJ, 2015, p.17.

- Moss definition inspired by Robin Wall Kimmerer, Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses 2003, p.7–13.

- Michael Arbib, ‘Toward a Neuroscience of the Design Process’, in Sarah Robinson, Juhani Pallasmaa (eds.), Mind in Architecture, Neuroscience, Embodiment, and the Future of Design, The MIT Press, Cambridge MA, London, 2015, pp.75–98.

- Jennifer Hahn, ‘Andrés Reisinger sells collection of “impossible” virtual furniture for $450,000 at auction, Dezeen, 23 February 2021, https://www.dezeen.com/2021/02/23/andres-reisinger-theshipping-digital-furniture-auction/ accessed 19 May 2021.

- Inspired by Juhani Pallasmaa’s talk ‘Body, Mind and Architecture’ for the 2nd International Symposium SISU – The Impact of Space in Tallinn, 27–30 May 2015.

- Anni Albers, On Weaving, Princeton University Press, NJ, 1965, pp.44–47.

- John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, ch. 3, The Nature of Gothic, 1851.

- Serpentine Podcast, ‘Future Ecologies, Enlichenment and the Triage of Life’, 7 August 2019.