The Timber Couturier

‘We’d go mushroom picking with my father; I’d be the one hunting for mushrooms on the ground, and he’d be looking up in search of the perfect trees for his future creations; he’d then inform the rangers of his choices, and they’d cut the wood for him,’ Bangutis Prapuolenis recalls while showing us around a two-storey workshop that once belonged to his father.

Jonas Prapuolenis is arguably the bestkept secret of furniture design in the history of Lithuania. Born in 1900 in a small town in the Suvalkija region, he moved to Kaunas to learn his craft as soon as he could, and never looked back. He later studied in Paris and took inspiration from the art deco furniture designer Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann. In 1937, the Lithuanian prodigy exhibited his work in the Lithuanian section of the Baltic Pavilion at the Exposition Internationale in Paris, where he was awarded gold and silver medals. Bangutis laughs that his father wasn’t too keen on farming, but it’s interesting that Jonas’ father was a carpenter and his mother was a weaver.

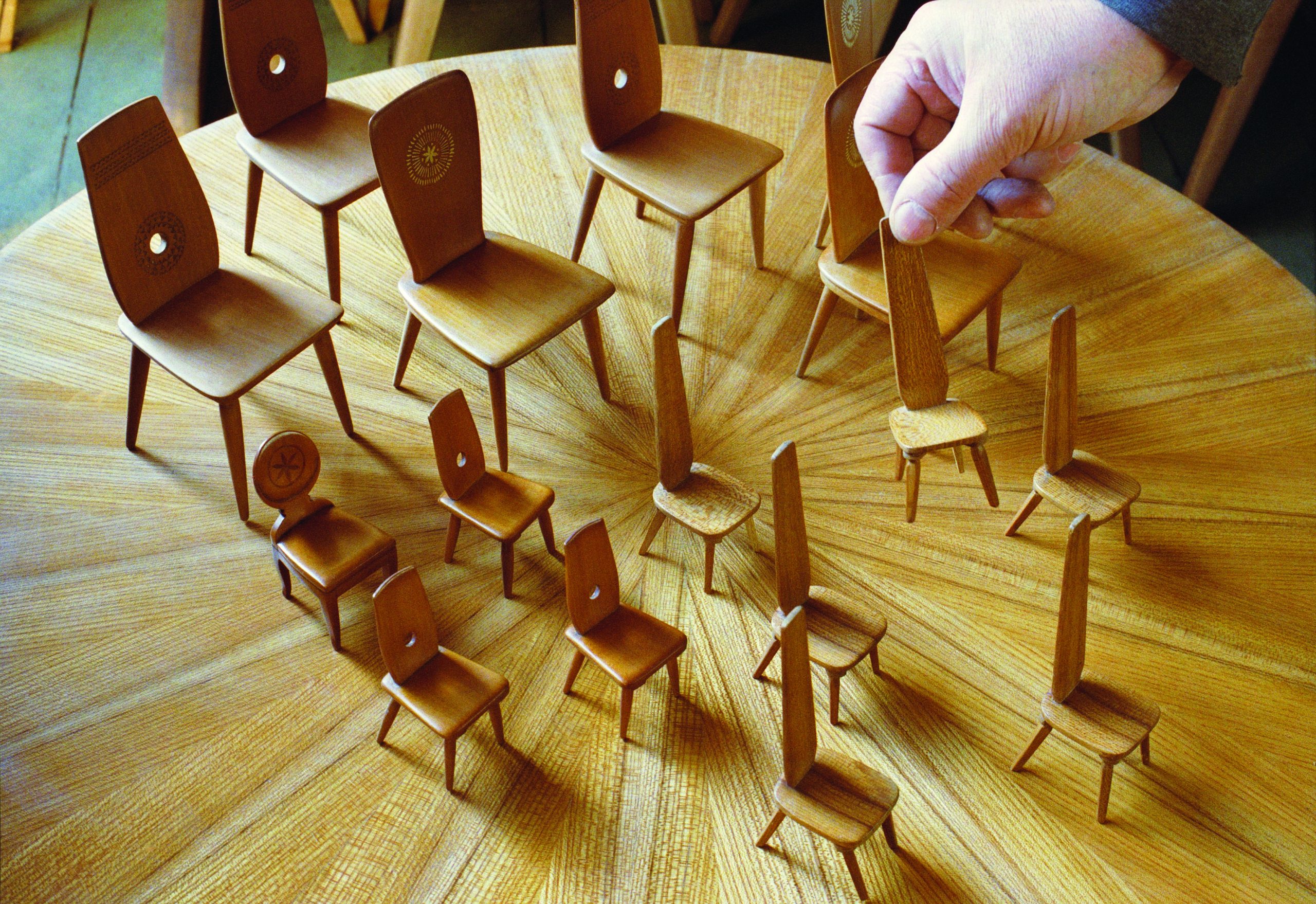

The ideas inspired by both interbellum Western fashion and Lithuanian ethnic motifs have survived the test of time. Prapuolenis’ precious work was valued by both the elite of Kaunas and, later, by the Soviet decisionmakers. Today, furniture enthusiasts looking to secure an authentic piece made by Prapuolenis have as much chance of winning the lottery. Bangutis, who was in his late teens when his father passed away, inherited Jonas’ talent and insightfulness; he is often commissioned to refurbish items owned by local museums or art deco aficionados. ‘My father had a principle not to copy himself – he’d make a single furniture set, one of a kind. Very, very rarely, he’d make similar versions, but only the original would be branded,’ recalls Bangutis, who’s also a lecturer in furniture restoration. In Soviet times, his father used to make prototypes for mass production but some designs were too elaborate for that.

Young Jonas was a volunteer in the Lithuanian Wars of Independence at the end of the first world war; and like other volunteers, he was given a generous amount of land in lieu of his services, on what was then the outskirts of Kaunas. The city, of course, grew, and just before the second world war Kaunas Clinics – the largest medical institution in Lithuania and the Baltic States – was built right next to Jonas’ land. Back in the 1920s however, Jonas found himself in a poplar grove and used the logs as building materials for his new workshop. He’d sleep there, too, as he didn’t care much for the comforts of his home. ‘He preferred to create beautiful things for others,’ Bangutis explains while serving hot coffee in porcelain cups and chocolate-coated biscuits. We sit down in the former workshop to warm ourselves up before moving on to the current one.

It’s easy to lose track of time while sinking into the wooden chairs made back in the 1920s for Adomas Galdikas – a famous Lithuanian artist and schoolmate of Jonas – and glancing over at the piles of vinyl records beside you. On top lies ‘Out of This World’ by Tangerine Dream. ‘Yeah, I like music,’ nods the only son of Jonas. Today, he’s the owner of the most extensive collection of Prapuolenis furniture. Museums are the runners-up. The Museum of Applied Arts and Design in Vilnius owns all of the furniture and other items made by Prapuolenis for the former Embassy of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic in Moscow. There’s an exciting story about it.

‘Romualdas Budrys, head of the Lithuanian National Museum at the time, went to Moscow to retrieve the collection when the Soviet Union collapsed – even the ashtrays there were made by my father. He once told me that, after packing all of the furniture, he walked around the estate and saw a few local workers sitting on a bench. He immediately recognised the Prapuolenis work and did not hesitate to take it too!’. The Moscow furniture is not exhibited, but a few of Prapuolenis’ sets can be seen in their natural habitat in the historic homes of artists and writers in Kaunas.

There’s more to the legacy of Prapuolenis than chairs, tables and closets. A delicate piece of his art has recently been refurbished in the Kaunas Garrison Officers’ Club Building. It is a wonderful interwar architecture heritage gem representing the subtle blend of modernist trends and national style. The piece – a weaved oak and ash tree parquet floor pattern in the main hall – has witnessed thousands of shoe soles and heels during its 80-something years of history. The staff had intended to replace it, but Bangutis and his colleagues managed to influence the decision.

‘Oh, my father also made jewellery from bone and amber!’ Bangutis adds as we start walking over to the workshop. But first, we must see the tabletop collection, which could easily pass as a painting exhibition.

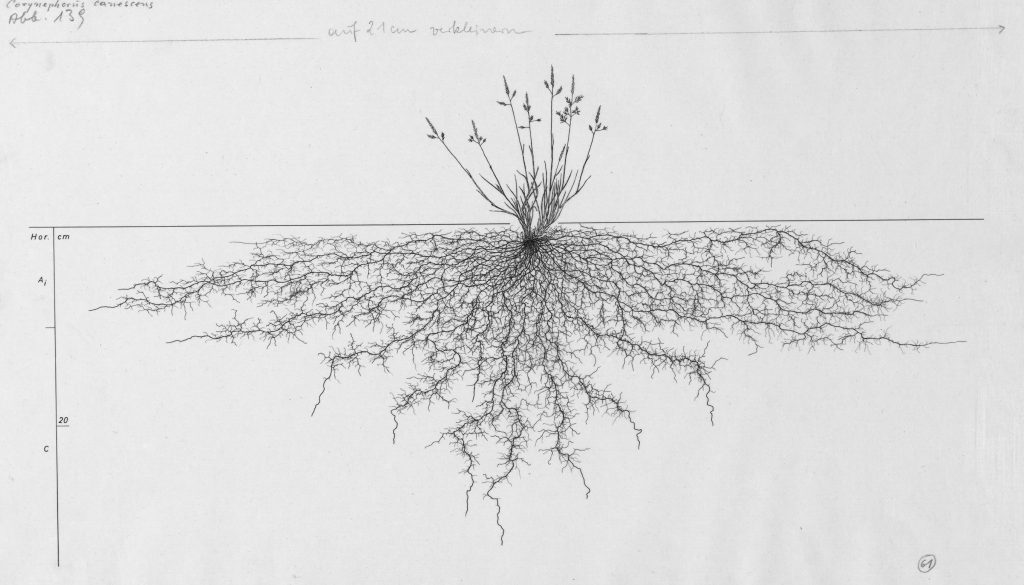

To mark Jonas’ 70th birthday, an extensive exhibition was organised. Together with his most prolific work, Jonas decided to show a variety of tabletops made from Lithuanian timber (he typically only used Lithuanian wood), including apple tree and ash. Each kind of timber and each individual tree has its own distinct texture, as if it were a language of patterns. Jonas developed a special technique of cutting logs into small plates to reveal a specific grain. Other artisans tried, unsuccessfully, to replicate and master this secret skill. Maybe – it’s a wild guess – the skill was down to the tools that Jonas used – machinery, hand planes, and shaving tools that he had made himself. These aren’t just tools but artworks in their own right – the handles are bird-shaped.

Another secret of Jonas’ craft – and one that Bangutis is still trying to master – is the use of wet timber. One has to know precisely how the moisture evaporates from a tree and what shape it will conceive. ‘Everyone knows how to make things from dry wood – but try the wet one!’ Jonas used to laugh. But it wouldn’t be fair to say he didn’t like to share his knowledge. After all, the new workshop was intended to become a craft school. He built it in 1939, and soon enough, the scenery changed. The Soviets occupied Lithuania; Prapuolenis decided it’d be best to leave the idea and save the house from nationalising and himself from deportation. His brothers were taken to Siberia. Jonas remained in Lithuania and started teaching in his former alma mater, and later in Vilnius, before settling in Kaunas for good.

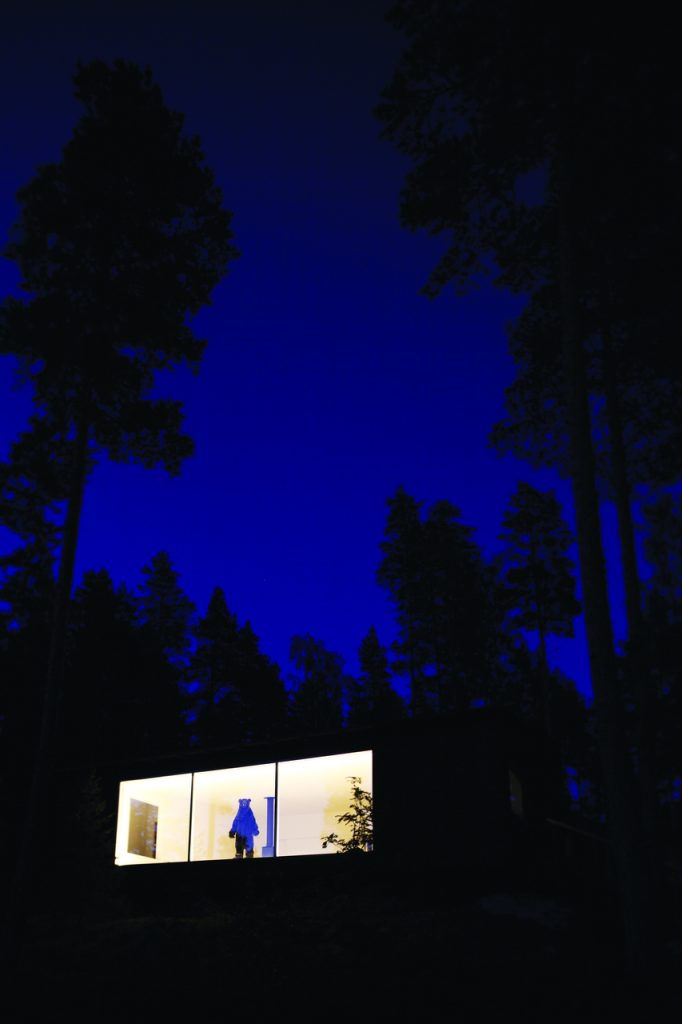

‘Perhaps I learned more from my father’s students than from him,’ Bangutis wonders while showing us a summer house next to the workshop. It’s his father’s last work. Jonas passed away in 1980, just a couple of weeks before his 80th birthday.

Kotryna Lingienė, is a Kaunas-based culture journalist and editor working with both text and audio. She has a background in architectural history, with a focus on the interwar modernist legacy in Kaunas; the former temporary capital of Lithuania.