And How Does the Fungus Feel About This?

When the topic of fungi came up (again) at one of our editorial board meetings on this issue of the magazine, one of the board members shared their scepticism and remarked ‘but fungi are discussed all the time right now, maybe we should be more original and leave it out of the Other?’ Indeed, in the field of contemporary art and culture, which is soaked with anxiety, burnout and inflammation, one of the recurring elements is fungi – their by-products and hallucinogenic properties – which can be consumed as food, prescribed as medicine, or change peroples’ perception of reality and ways of thinking. However, does simply consuming a mushroom and being affected, perhaps even inspired by it, yield results limited to superficial thinking? Once we have agreed that the kingdom of fungi is more powerful than anything we know, should we just stop and enjoy the delicious but very limited fruits of our work?

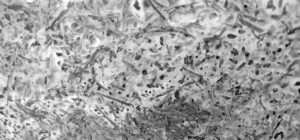

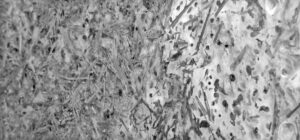

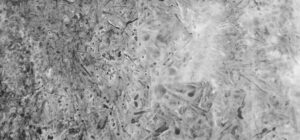

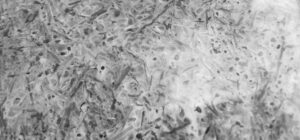

It is the unknown, specifically, that motivates architect Šarūnas Petrauskas. Since 2019, he has been researching mycelium and is particularly interested in the living form of this matter, widely present in nature and so far rarely considered when thinking about the architecture of the future. In our discussion, we talk about his artistic research Hypha, which means ‘network’ in Greek. Hypha is a branched, tangled, and densely intertwined filamentous structure. Countless thin hyphae form mycelium, which is what we call the fungal network. In the autumn of 2023, Šarūnas presented the third stage of his project – biomorphic mycelium structures – to the public. He invited an audience to observe a mushroom growing in a terrarium and reflect on how we might grow spatial structures from mycelium that could be adapted to human activities. However, before delving into the ‘how’, let’s get to the bottom of why this is necessary and meaningful.

–

Šarūnas, what prompted you to follow such an untrodden, unfamiliar path? The need to stand out from the crowd, the search for something new and different, the need for sustainability? Given that you started experimenting as a student, I’m curious to know whether you had to prove the importance of your work to your professors and fellow students.

The aim of any study is to discover something new. Doing something that has been done before is meaningless and uninteresting. For that reason, you move forward without necessarily knowing where you are going or what you might find. My research as a student focused on the application of natural principles in architecture. It can be called biomimetics, biomimicry, or biomorphic architecture. Fundamentally, I was interested in how nature is used in architecture – through various aspects, from the use of mimicry and visual elements in space, to the application of specific principles that have been discovered. For example, the well-known golden ratio was discovered in the pursuit of perfection through an exploration of natural structures.

However, the deeper I delved, the more I realised that we really know nothing about nature; we don’t learn from it, and therefore, we don’t apply its principles. We are only able to use its materials to create living environments – that is, by irreversibly exploiting natural resources.

Among the architects who have managed to learn from the laws of nature, I would highlight the German architect Frei Otto, who researched tensile structures, observing, for example, soap bubbles and applied his findings to a completely different architectural expression [Editor’s note: he is most famous for his contribution to the research behind the lightweight roof structure of the Olympiastadion in Munich]. Another such architect is Buckminster Fuller, who patented and popularised the geodesic dome. We have done nothing new in this specific field; we have only repeated what he did more than 70 years ago.

This is why I was eager to do the research. I was interested, but I realised it was a big challenge. I asked myself: Why am I getting into this if others are not and aren’t learning? The initial process was difficult: for about a year and a half, I was solely focused on researching what had already been done, what was currently being done, analysing buildings, constructions – admittedly quite primitively. The conclusion I came to was quite stark: in architecture and construction, we simply cannot talk about sustainability or about turning back to nature. We are not giving anything back to nature.

Of course, both my colleagues and professors questioned what I wanted to achieve. I talked about finding new expressions – I remember someone asked me, as a joke, if I wanted to invent a new typology. And so, over the course of these discussions, an idea arose – could we, broadly speaking, just grow a house? That’s when I got hooked. I started looking for ways to do it, because the very idea seemed unheard of and unseen. After all, most houses are built, not grown.

I lived with that idea for a long time, wondering how nature might build and grow a house, until I found myself in the kingdom of fungi. Of course, I also found the aesthetics, the visual expression, exceptional. Then the technical questions of how it could happen needed to be addressed. All of this by way of experiment. Simulating the patterns, observing live growth, exploring how much it can be controlled, or whether mycelium is a life form independent from us.

The phenomenon of nature is the opposite of the principle of determinism, embodying chaos principles and nonlinear dynamics. Chaos follows the rules of determinism, but these rules are so irregular that they even appear random. The mixture of regularity and endless structures in nature creates the impression of infinity. Phenomena that appear random have a hidden order waiting to be revealed. Often, chaotic and irregular phenomena are based on very simple rules and structures.

Experimentation confirmed my ideas – yes, growth can be controlled, mushrooms can be shaped, and spaces can be created in this way – and this is what I presented in my final thesis. My hypothesis was confirmed; theoretically, it is possible to grow a house. It was still difficult for those around me, and even me at times to grasp. There were many questions – what is this thing? The substance is strange. These are the roots of mushrooms. You have to explain schematically what it is, and why it is from this particular vegetative mycelial network of hyphae that mushrooms sprout.

While looking for a way to explain it to others, I convinced myself that it was possible. But it wasn’t easy. It wasn’t as smooth as I had hoped. Many people didn’t understand what I was doing. I don’t even know if I understood what I was doing at the time. There were people who were holding me back, who were quite critical of this experiment. Others didn’t understand but encouraged me to keep going. They saw it as an important turning point in creative architectural processes, something radically different, like a new species.

Of course, I’m not trying to claim that fungus has never been used in design. There have been attempts in global practice, though perhaps more often in interior design or furniture design. A few years ago, a ‘growing pavilion’ was presented in the Netherlands, but it was not a living structure; it was a display of dead mycelium.

Yes, the substance is interesting. But it’s not the material itself that interests me, rather its use in the creation of spaces. After all, no substance is relevant if it only exists by itself. Its significance is determined by the relationship it has to its environment.

It is precisely because there is no experience, no methodology, just theoretical considerations that we have only worked with dead mycelium so far. But fundamentally, it is no different from wood – you grow a tree, you fell it, cut it into boards, and build a house from it. No innovation. A living space could change over time, adapt, adjust. It would feed on organic matter, repair itself, patch itself up if necessary, and continue the cycle until it disintegrates into its original state and returns to the soil. Such a process is 100% natural and sustainable and would constitute a serious alternative to the modern construction industry.

What are the differences between the three phases of your Hypha project, the last of which you presented at the AX-Y pop-up architecture gallery in Kaunas? Is each phase a progression or a new approach to the problem?

The principle is similar, everything follows the same logic – each phase is the search for the right methodology. I use the same matter, mycelium, in each phase, but the types of fungi are different. I use saprotrophs, fungi that feed on dead organic waste such as straw. In the last study, I grew the mycelium of the tinder fungus (Fomes fomentarius). The structure, surface and other details vary depending on the species. I look at what the fungus grows on and interacts with and what kind of organic matter – cellulose, cardboard, straw – it feeds on. What structures can be grown? How can they be influenced? After all, we need to create the right environment, a very different one from that preferred byhuman beings or plants, for example. A fungus does not need sunlight; it does not use it as energy. I control the growth of the fungi with temperature, light, moisture and food. That is the frame in which I practise.

It all started with my Master’s thesis, which I defended in 2019. A little later, I presented Hypha.01 – archetypal spatial structures such as the arch, the column. Essentially, I demonstrated that it is possible not only to build by conventional means, but also to grow functional primary architectural elements. In the second phase of the project, more abstract spatial elements emerged, along with broader explorations of their interaction with other materials. This was followed by a desire to grow a structure and exhibit it as a living object, an organism, a living space. This was a significant challenge as such an experiment requires the sterile conditions of a laboratory. After all, fungi are sensitive to bacteria and other organisms in the environment.

I decided to take a risk and grow mycelium in the gallery space and in the architects’ office. Basically, the experiment half succeeded and half failed. The structure didn’t grow quite as we had hoped, but that’s waht’s interesting. Creation doesn’t always work the way the artists imagine, as in ‘it has to be like this and can’t be otherwise’. Because, precisely, things happen that you didn’t foresee, or things happen differently, in a different place. Well, the structure worked well, we managed to shape a space within it, and a living model was exhibited in the gallery. The unexpected element was the appearance of other fungi that started growing there. It wasn’t what we intended or expected, but it added to the realism of the experiment and even diversified its visual expression. I think it gave clarity to the audience because the material didn’t appear homogeneous.

Overall, I think that the project should be alive, not methodically produced, documented and terminated. The different stages provide knowledge, time and space for testing. There is a lot I don’t yet understand and can’t control, but I can see the potential in it.

Under favourable circumstances, fungi perform decomposition – they penetrate, break down and decompose organic matter. They prepare the environment for other life forms. Or they contribute to cleansing the environment of certain human by-products. They restore harmony.

As you were talking about how others related to your experiment, I wondered whether might be because the words ‘fungus’ and ‘building’ together might evoke associations with mould that many people know and have experienced. Hearing these words might trigger a rejection reaction.

But now I would like to ask how you see your role in the process? What is the relationship between design, construction and growth? Can growth generally be considered a type of construction?

I’m not sure it’s possible to make a straightforward comparison. They are two very different processes. Of course, both involve creation, but in the first, growth is natural, while in the second, it is forced. Someone else does the building while the growing happens on its own. So I would not compare the two processes. If we were to apply the growth of living matter to the process of creating spaces, it would be a whole new expression of creativity. I haven’t seen that yet, but that’s what pushes me forward, the desire to create an object, a living and growing spatial structure.

As for the association with mould and the rejection reaction … We are generally sceptical about anything we don’t know or understand. We are scared by the prospect of not understanding something. For others, this is the great challenge – to accept that they don’t know something. You can’t show it, your authority doesn’t allow you to not know something. And the more I delve into it, the more I realise how little I understand. You plan something because you expect it to happen in one way, but it happens quite differently – that’s where the sense of not knowing comes from.

Different species of fungi grow and develop in different environments. However, in many cases, they adapt and colonise not only plant roots but also other organic and inorganic matter.

Actually, this is one of the problems in wooden construction – living fungus consumes non-living wood. They can also colonise and destroy concrete and other surfaces. There are species of fungi to whom, figuratively speaking, this is a delicacy. We are in no way protected from this. They simply grow, or don’t, in the environment that surrounds them. Sometimes we can control this, sometimes we can’t. All of this is basically out of our control. We cannot control nature.

And is the cultivation of a living structure not an exploitation of nature? How is itt different to cutting down a tree and growing another in its place?

I could compare it to growing a tree, or another plant, for the oxygen it produces. In this case, although fungi do not produce oxygen, they enrich biodiversity and are an integral part of the ecosystem, significantly contributing to the sustenance of other forms of life. Growing mycelium expands the amount of living nature.

But if we consider exploitation to be when a person benefits from fungi, then yes, of course. Does nature suffer from this? I don’t know how to measure that in this case. And how does the fungus feel about this? Let’s imagine – if it is growing, then it feels good, it is thriving. If it stops growing, then something is wrong; the conditions are not right.

The very profession of architecture itself raises the question of how it is positioned – is it science or art, or a fusion of the two? In this particular case, the question seems even more relevant. Is it more important for you to express yourself as an architect, which is not always possible during working hours, or is this ongoing project also a scientific ambition?

For me, it’s both – I call it a hybrid process. It’s important to note that this process is determined not only by my efforts but also by non-human intelligence. It is this intelligence, not humans, that is responsible for the perfect natural aesthetics, which changes over time.

Although I have no ambition to make a scientific discovery, it would be nice. But that is not the immediate goal. I would like to develop a methodology, and I would like it to be more widely applicable. At the same time, it’s interesting to explore the creative fringes, the so-called margins. There is indeed something conceptual and different from what is currently dominating the media. It seems to me that although there is a clear distinction between what we call relevant and contemporary and what we call old or old-fashioned, we are actually repeating the same thing over and over and just moving in cycles. Of course, technology is improving, yet the materials and forms keep repeating. I don’t see the radical leap that I want to see in the architecture of the twenty-first century, something clearly different from the architecture of the mid-twentieth century. Steel, concrete, glass – we play with the same materials, but what changes? Yes, we are paying more attention to energy consumption, but does this contribute to the overall human condition, the microclimate, our well-being, the search for new space, the search for architectural expression? There are grand ambitions, but there are few sincere efforts or valuable outcomes.

The roots of fungi and the structures they create tend to develop radially from the centre outwards, forming spatial structures similar to spatial stains.

I set myself the task of moving the project forward. I already know that it is possible to grow a space, so I will continue with my original idea and strive to do so, expanding my perception at every stage and looking at what I have learned to see where I can go next.

Maybe you’ll be able to grow a cabin in a few more years?

Maybe, maybe, maybe. It’s a utopia due to the environmental nuances. But I think I’ll be able to grow a small structure. A space accommodating the human body is possible. Whether it will be a cabin, I’m not sure.

Is there a theoretical possibility that the human-sized structure you are planning would thrive and take over what people have already built?

Of course. Fungi dominate in general. We just don’t notice it because we don’t know them. It seems like we humans control and oversee everything, but they are everywhere. Just like pollen, fungal spores are widespread. Of course, there are fewer in urbanised areas and more out in nature. We see some species, but not all of them. It would be interesting to see how they occupy the existing environment. Maybe it will happen. We are afraid of what we don’t know, but in spite of our fear, fungi are part of our environment. So we need to find the right relationship. I wouldn’t be afraid of it, instead, I’d see it as an opportunity. We should prepare for the arrival of fungi in our everyday life. Just as people grow plants, they could grow walls.

After all, this is the artistic meaning of the unknown – when the viewer doesn’t necessarily understand why, but likes it, finds it beautiful nonetheless.

Yes, indeed. And it also makes you pause when you realise that you aren’t familiar with the process, but it’s interesting. Some people’s opinions changed – they were very sceptical at the beginning, but then they realised that it’s not just an image; it abides by the axioms of statics, for example. The structures do not collapse, they can bear weight, they are functional. They seem to take it more seriously once they realise that, or maybe they just start believing it.

I haven’t met many architects who can advise me on methodological issues, but I received a lot of support for the conceptual nature of the project. Many are interested in the idea itself, but not in the further possibilities. That’s why I’m interested in connecting with professionals in other fields. I talk to naturalists, mycologists, biologists, pharmacists and other specialists. In the Hypha project team, there is a mycologist who helps me a lot. I need advice because I lack the knowledge myself. It’s good that we are both able to see not just the pragmatic side but also the aesthetic one. Meaningful debates among peers are crucial and incredibly helpful; otherwise, projects can perish solely due to a lack of knowledge.