Another Hundred Years

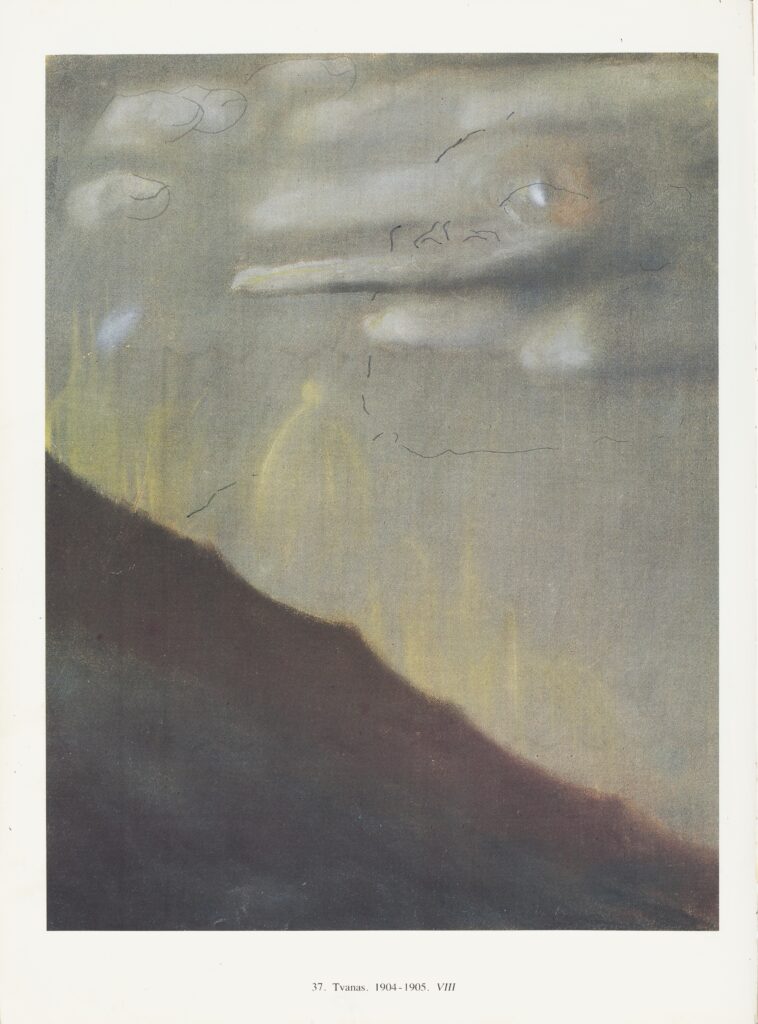

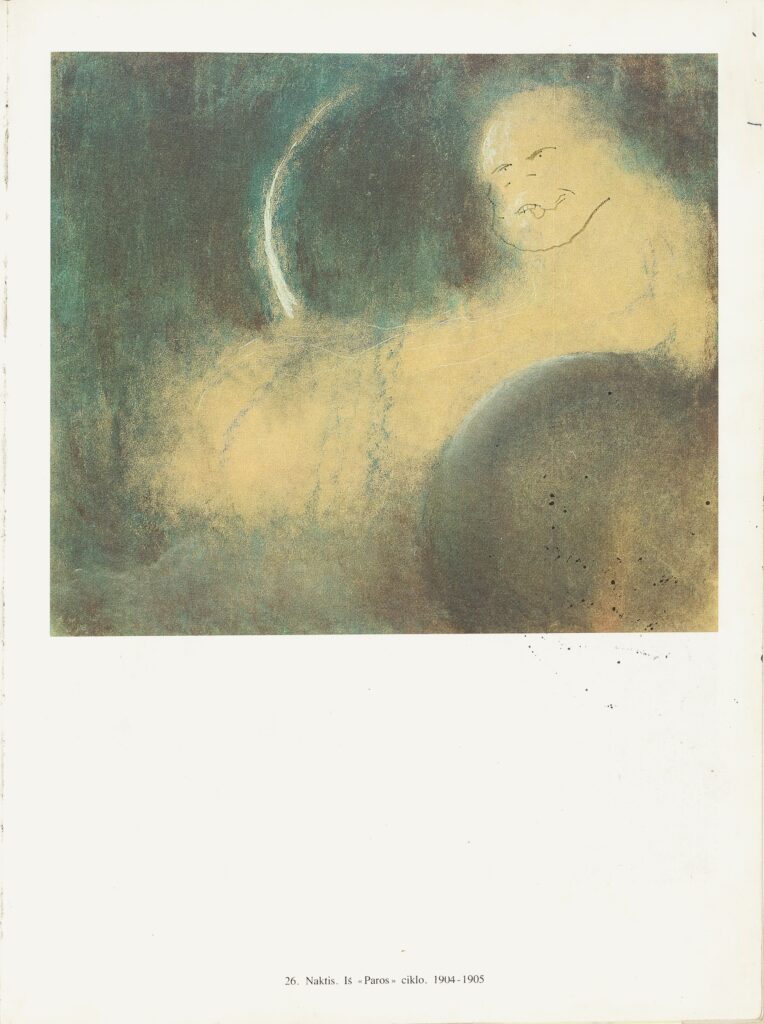

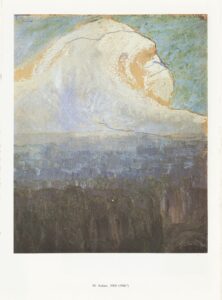

Donatas Jankauskas–Duonis. Pages from Marčiurlionis, artist’s book, series of 9, circa 1997 – ongoing

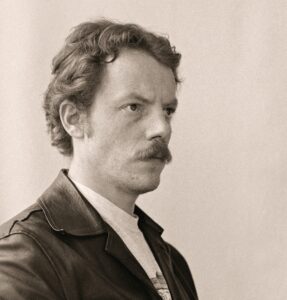

Asta Vaičiulytė: Thinking about your work and M.K. Čiurlionis, I was reminded of one of your first solo exhibitions – ‘Retrospective’, held in 1999 at the Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) in Vilnius when you were only 30 years old. This exhibition presented all of your work up to that point, including several works that highlighted the theme of Čiurlionis. Among them was your artist’s book, Marčiurlionis, a catalogue of Čiurlionis’ works onto which you made additions using various drawing and collage techniques. The exhibition also featured sculptural installations and a video work based on the motifs of Čiurlionis paintings, and a drum’n’bass remix of Čiurlionis’ music piece. Shaped as an all-encompassing installation, the exhibition also included a striking photographic portrait of you posing in the style of the iconic image of Čiurlionis, complete with similar hair and moustache. Perhaps we could start with the book Marčiurlionis – a series of nine artist’s books, each different. More than once, I have read or heard you describe it as a database of your ideas, from which you continually pull out individual elements that later evolve into larger works.

Donatas Jankauskas–Duonis. Pages from Marčiurlionis, artist’s book, series of 9, circa 1997 – ongoing

Donatas Jankauskas–Duonis: Speaking about the beginning, I once had a children’s book by Bidstrup1 in my studio – essentially, a propaganda publication about fascists. A group of work colleagues regularly came to my studio, and we would deface it by drawing cigarettes on all the kids in the book, which completely changed the context. By chance, I also had a Čiurlionis catalogue, and I started my Marčiurlionis book in the same way. Right away I had the idea of making multiple versions of them. I started with one book, then I had three. I gathered them from my parents and friends.

AV:

Back then, that edition of Čiurlionis’ catalogue could be found in almost every home.

DJ–D:

Yes. To make things calmer, when everyone is doing something, you could pull out the catalogue, without drawing anything, and just flip through it. Among the works exhibited in ‘Retrospective’ were the installations Anxious, Forest Music, and the lightbox A Lie. The exhibition also featured a Čiurlionis’ prelude played backwards – it turned into a detective-like melody, similar to the theme tune of The Pink Panther. It played relentlessly at the CAC for an entire month, with people constantly going to turn it down.

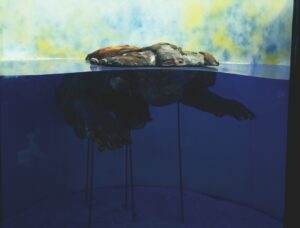

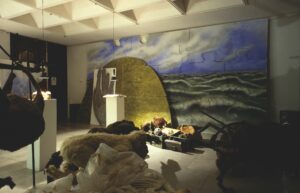

Donatas Jankauskas–Duonis, Anxious, installation, 1999 (part of the exhibition ‘Retrospective’).

Photo: Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius archive

AV:

In that exhibition, you were essentially remixing Čiurlionis in various ways and formats – through installations, video, and, with other people’s help, sound.

DJ–D:

As I say, it’s light hooliganism. Like when you see a scene through a car window and think, ‘Čiurlionis’. You notice similarities and specific patterns.

As for growing out my hair for the portrait, there’s another layer to that. There’s a famous basketball player, Šarūnas Marčiulionis, who at one point had bangs similar to those of Čiurlionis. The title Marčiurlionis came from a wish to combine Čiurlionis’ image with the mindset of an athlete because I was doing a lot of sports myself back then.

AV:

Your relationship with Čiurlionis seems to have emerged in various forms simultaneously.

DJ–D:

Perhaps it didn’t emerge. When you graduate from Čiurlionkė3, it’s, you know, like graduating from the Komsomol.

AV:

… indoctrinated with Čiurlionis?

DJ–D:

Exactly. From the moment you enter the assembly hall, you’re confronted with him – the leader is already there.

AV:

Because his portrait hangs in the assembly hall?

DJ–D:

Yes, but it’s more than that. There are other elements too – the school anthem plays; the wave is crashing … I still remember how it gave me chills. We’d listen to the anthem and then everybody would sit down. As one of my friends says, ‘I still feel the damage the Soviet era did to me.’ Čiurlionis also did a lot of damage.

AV:

So, would you say you’ve been digesting that strong impression of Čiurlionis in your work throughout your life?

DJ–D:

Over time, it simply becomes a way of life because you don’t look at it any other way. It’s not like I consciously turn to Čiurlionis as one would to Beethoven and become all ecstatic … But as we were taught in school – for example, while being shown Mikėnas4 – everyone drew ideas from folk art.

AV:

Čiurlionis’ works are undeniably an important reference point in Lithuanian art.

DJ–D:

When we find out how much Čiurlionis’ works cost, then we’ll know our own value.

AV:

Well yes, his works are an invaluable national treasure, not to be sold. You’ve already mentioned that you couldn’t avoid your relationship with him. I’ve also read that you said that by returning to his works, you continue to discover aspects that others might overlook – that they hold both mystery and, at the same time, a very simple language. You’ve said that he is part of our national artistic school and that, in a sense, we have not strayed too far from it.

DJ–D:

Of course, he’s recognisable … By the way, a few years ago, a new catalogue of his drawings was published. I was at the Čiurlionis Museum5 at the time, and there was a discussion about whether to include his drawings that lean towards caricature. He actually had a great sense of humour. Take, for example, the portrait of his brother with the monkey or some of his drawings from St.Petersburg. If we look closely at what he drew and painted – his thoughts and his surroundings – we’d see everything running in parallel: his music, his paintings, and his pastel works.

AV:

Yesterday, while preparing for our conversation and flipping through Čiurlionis’ catalogue, I found myself thinking that his imagination takes one away – especially considering how little information and imagery people had access to back then compared to the vast amount we consume today. At the same time, his works are playful and they genuinely make you smile. You mentioned he had a good sense of humour, and I too have a similar sensation when I look at them. Would you say that, in a way, they naturally provoke the narratives in your own work?

DJ–D:

You have to look specifically … Take, for example, the painting Flowers. There’s this sense of grandeur, almost pompousness, and then, at the bottom, you have these little fuckers – these little people kneeling down.

And then there are his compositional techniques … What does it even mean to draw from someone’s work? And what kind of ‘school’ is that anyway? I don’t even know where to begin. You can start anywhere, with any work. Perhaps it’s slightly more complicated with his music though. For example, the pianist Donaldas Račys, who performed the piece for ‘Retrospective’, said to me, ‘Look, I don’t get it, why has he got this flat note here … it means your finger has to be twisted. And the sound is so strange …’ Čiurlionis has his own distinct style in music as well.

Donatas Jankauskas–Duonis. Pages from Marčiurlionis, artist’s book, series of 9, circa 1997 – ongoing

As for the Marčiurlionis books, sometimes it’s as simple as adding a dot and it’s done. But in other cases, the work just flows. Each of my Marčiurlionis books differs slightly in their print quality.

I was talking to the Čiurlionis Museum the other day about what to do next year6, and I told the director, you know, let’s give Čiurlionis a rest, let’s take him down for a while because he’s starting to fade. It’s like the sculptures in Greece – their marble was once painted but the colours faded over time. And Čiurlionis is fading too, which is why it is good that we have this derivative version of his work in the book. When you look at the original, of course, it’s something completely different … And this is a copy. But the facts are all there. And of all the versions of Čiurlionis’ books, this one is the best. The other books are more statistical but this one is really well put together. Everything is clear – the sequence, the cycles – it’s all there. If we were to add the newly published drawings, it wouldn’t have the same strength. But this book has both a beginning and an end.

AV:

I agree, I really enjoyed going through it yesterday. I also think you’ve described it very accurately – the spectrum of his work ranges from mystery to very simple language. In fact, some of Čiurlionis’ works look like they were created with a very light touch, without overemphasis, whether in his paintings or especially in his drawings. In this sense, could we say that he was a very versatile, broad-spectrum artist?

DJ–D:

I think he could have even danced ballet. Or gone to dances. There are hints of dance in his work. Why else would he choose these kinds of landscapes? Čiurlionis is very scenographic, symphonic, even operatic, I’d say. He is also a great storyteller for a child – only his works aren’t fairy tales but hyperrealism.

AV:

That makes me think – maybe his work is like good literature from which other things can be made, like a great play?

DJ–D:

Yes. And as for my working method, I turn to a Čiurlionis book when a situation arises, comic or otherwise memorable, that needs to be immortalised. But I immortalise everything through monkey figures that resemble people. I might add a monkey’s nose in one place and a hand motif in another. It’s like in Čiurlionis’ own work – if you peel away one layer, you see how much has gone into it before it reaches the final result. You can sense there has been some suffering there.

Donatas Jankauskas–Duonis. Pages from Marčiurlionis, artist’s book, series of 9, circa 1997 – ongoing

AV:

Could we say that Marčiurlionis is a kind of sketchbook for your future works?

DJ–D:

Maybe it is more like a book of everything, or rather, books. When I have a task or a question I want to explore, I look for the answer in the book. They already have scripts in them, and I’m like a DJ, jumping between the same themes – opening the same images in different books at the same time.

AV:

You mentioned body parts and monkeys, and monkeys are indeed another recurring leitmotif in your work. Did you naturally start seeing them in Čiurlionis’ works?

DJ–D:

It’s like placing that little dot … Sometimes the pigment stain is already in the painting, and then it starts to stand out.

AV:

Perhaps the monkeys, being similar to us but also slightly different, help us see ourselves – as a culture – from a different perspective?

DJ–D:

In the village of Piliuona, I had a sculpture called The Birthday of Venus – two monkeys in a clam shell. I can’t say for sure, but if, say, two hippies were in the shell instead … Basically, when the relationship between two people is depicted, it becomes terribly banal. But when you look at a monkey, you start looking for connections, you recognise things, it’s like looking in a mirror. It’s hard to constantly answer the same question ‘Why monkeys?’. I already have about thirty answers. One of them is – ‘Why not?’ A monkey represents an unspoken truth. It’s always silent. We don’t know what they think; they are incredibly good at pretending to be beasts … And they are very similar to us.

Donatas Jankauskas–Duonis, The Birthday of Venus, installation, 2022, water tower in Piliuona. Photo: Martynas Plepys

AV:

In your work, existential motifs often merge with everyday scenes, incorporating a symbolist, Čiurlionian dimension and a certain irony, humour, and quirkiness. It feels as though you are reflecting on culture in a broader sense.

DJ–D:

By translating these ideas into everyday language, you can tell a completely different story – one that’s not so grand.

AV:

As you’ve said elsewhere, you speak through big, simple objects …

DJ–D:

… small literature, big objects.

Donatas Jankauskas–Duonis. View of exhibition ‘Retrospective’, 1999. Photo: Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius archive

AV:

I’d like to return once more to the ‘Retrospective’ exhibition. It carried a certain irony about the figure of the artist and historicity. It disrupted the principle of the retrospective exhibition – you were still a very young artist, and all your works were exhibited without any selection. The curator of the exhibition, Raimundas Malašauskas, published the text Becoming Not-Self. It was a slightly reworked version of Alfonsas Andriuškevičius’ essay Becoming Oneself, written about the then-young sculptor Petras Mazūras. In Raimundas’ text, Mazūras’ surname was replaced with yours and minor adjustments were made to some of the factual details.7 I see a certain similarity here with the Marčiurlionis book.

DJ–D:

Raimundas initially pushed for the exhibition, but I already had ideas about how to construct it. I started to pile everything together, and it all happened spontaneously. For example, I bumped into Kemežys8 at the CAC – we were both working there at the time – and I said, ‘Take a photo of me’. ‘Alright’, he said, ‘I’ll bring the camera’. I was sweaty, wearing a T-shirt, but I threw on a jacket. I opened Čiurlionis’ book, which has his portrait in it, and I looked at my reflection in the window of the CAC courtyard on the first floor. I asked him, ‘What do you think, does it look similar if I stand like this?’ Click. It took four takes to do it. We chose one of those photos. Others agreed it looked similar. That portrait of me ended up hanging in a winery – people would say ‘Yeah, I know, that’s the painter, Čiurlionis.’ It’s like KFC or Che Guevara on a T-shirt, it’s like a brand – you get confused, you get mistaken.

Donatas Jankauskas–Duonis, Marčiurlionis, photograph, 1999. Photo: Audrius Kemežys

AV:

And what does it mean to continue creating after you’ve had a retrospective exhibition at 30?

DJ–D:

Initially, there was no intention to make it a retrospective. However as I started to bring my studio environment into the CAC, it merged with the exhibition space and turned into a retrospective exhibition. It was both a fictional and anecdotal situation because, for example, some friends even ‘buried’ me … Sometime after the exhibition, I was driving in Palanga and we passed by with those friends in our cars. They turned around, caught up with me, and said, ‘We didn’t make it to the funeral, but it turns out you’re alive …’

Donatas Jankauskas–Duonis, Forest Music, installation, 1999 (part of the exhibition ‘Retrospective’).

Photo: Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius archive

AV:

They thought … DJ–D: … that I had died. AV: And that’s why you had a retrospective exhibition …

DJ–D:

Posthumous! And imagine, these were close friends who could have just called …

AV:

Well, yes, thinking about it now, that exhibition also featured your personal items and other attributes – letters, reviews of exhibitions and works in the press, recommendation letters, your portrait. The exhibition itself paraphrased the survey format, which could be interpreted as a posthumous exhibition. In that sense, was the reference to the figure of Čiurlionis significant in the exhibition? Or did everything simply come together intuitively given you had works based on his motifs?

DJ–D:

The exhibition showcased everything I had created up to that point. It included two new installations and a lightbox made especially for the show. There was also a new, now-lost video work Forest Music about a wild man. Back in Čiurlionis’ time, people didn’t have warm, puffy synthetic jackets – they were freezing in the winter. The video was about that – how well we live today compared to then, and the need to toughen up. Of all the things in my work that relate to Čiurlionis, the monkey line is the noblest – they are sacral everywhere – intelligent, harmonious, and spiritual. But there are also ‘X-files’ and other associations in Marčiurlionis. And I don’t think I’m the only one who takes inspiration from Čiurlionis. I think Hollywood has a catalogue of his work as well. My book feels like some kind of test. People have told me they’ve flipped through it and can no longer look at Čiurlionis in the same way. Seriously, I can’t either.

Donatas Jankauskas–Duonis, Forest Music, video, 1999. Film stills

AV:

Is it fun for you to create your work?

DJ–D:

Well, it’s not dull. As those who work with stone say, the real joy is in coming up with the idea. Then, during the execution, it turns into boredom. After that comes the public reaction, and finally – peace again. But it’s unsettling to think – will it fall, will it float away, will it get destroyed?

AV:

And how much of this process involves self-reflection? Both in terms of the format of the ‘Retrospective’ exhibition, and the monkeys and existential motifs in your work.

DJ–D:

Perhaps it’s a sport, after all.

AV:

In the sense that art is like sport?

DJ–D:

Well, no, maybe not art itself, but the act of making art is like sport. One where you can do whatever you want – chess, golf, water skiing …

AV:

Is the method or the idea of a remix important to you – the use of existing images and motifs?

DJ–D:

You know, if we take it literally, we could say that just as Raimundas rewrote the text, I rewrote Čiurlionis. But ‘remix’ isn’t the right term.

AV:

What would you call it then?

DJ–D:

Maybe a kind of dressing up? We could think of Čiurlionis as a national school – a camouflage hiding a degree of asociality. Total independence is total asociality. If you hear music and the next day you write a text, not necessarily about that music, is that a remix? Just because the idea came to you while listening to some rhythm? Čiurlionis’ moustache and pose might seem ironic, but they could also be taken very seriously. And in my case, the seriousness lies in the harmony of Čiurlionis.

AV:

Harmony?

DJ–D:

Harmony, perhaps … In his harmony, even my monkeys become harmonious.

AV:

So, if we were to summarise, in the end, what does the figure of Čiurlionis’ mean to you?

DJ–D:

For me, Čiurlionis represents the whole, in which everything is ideal: Sofija9, his studies, the period … And I think I wouldn’t even be surprised if I heard his voice. In fact, we have something very real here. And it’s strange how, in preparation for this anniversary year, there’s this sense of transience – renaming the airport after Čiurlionis, organising various commemorative events. He needs to be sold. One of his works should be auctioned for the occasion. And then let him rest. A year in darkness so that he can last another hundred years.

Translated by Karilė Vaitkutė

Asta Vaičiulytė is a curator and art publications editor working at the Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) in Vilnius. Among other projects, she has curated and co-curated solo exhibitions by artists Jochen Lempert, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Jos de Gruyter & Harald Thys, Melanie Smith, and Algimantas Kunčius. Between 2012 and 2016 she worked in a curatorial collaboration which focused on the experiential, the material, and the elusive within the contemporary art field and explored non-verbal perception and ways of alternative exchange. This research resulted in three international group exhibitions; ‘Ritual Room’ (2013), ‘Words aren’t the thing’ (2015), and ‘Anachronikos’ (2016) at the CAC, Vilnius. In 2017, she was a co-curator of the Lithuanian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, presenting artist Žilvinas Landzbergas, and in 2018 she co-curated the video programme ‘Fast Forwarded: Selected Lithuanian Video Works Since the 1990s’, which was screened at MAXXI, Rome. In 2022 she edited Conversations about Lithuanian Contemporary Art, a book published by the CAC featuring 30 conversations with artists, curators, art critics and other cultural figures who have shaped the Lithuanian contemporary art scene over the past 30 years.

Donatas Jankauskas (Duonis) is an artist working across sculpture, installation, and video, as well as creating puppets, sculptural objects and costumes for theatre. Since 1990 he has actively participated in exhibitions in Lithuania and abroad, organised artistic actions, and street art festivals in Telšiai between 1997 and 2000. His works are characterised by monumental, zoomorphic figures and a wide range of references – from Lithuanian folk traditions, the work of M. K. Čiurlionis to contemporary popular culture. Often infused with humour and (auto)irony, his practice engages with multi-layered cultural and social phenomena. Work by Donatas Jankauskas (Duonis) is in the collections of the Lithuanian National Museum of Art and the MO Museum. He has also created several publicsculptures, which can be found in Sapieha Park, the Paupys district of Vilnius, the sculpture yard of the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius and other locations. Since 2006 he has taught at the J. Vienožinskis Art School in Vilnius. In 2021, he opened Bezdžiuonių muziejus (‘The Monkey Museum’ in Samogitian) in Savičiūnai, where he lives, displaying a collection of monkeys that he has gathered and created.

1 Herluf Bidstrup (1912–1988) was a Danish cartoonist and illustrator. He was a firm supporter of communism and deeply engaged with the international affairs of his time and social satire.

2 Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis [Catalogue]. Ed. Valerija Čiurlionytė-Karužienė and Judita Grigienė (Vaga, 1977). Reprinted 1981, 1984. A conversation between Asta Vaičiulytė and Donatas Jankauskas–Duonis (p. 129)

3 National M. K. Čiurlionis School of Art.

4 Juozas Mikėnas (1901–1964), one of the most prominent Lithuanian sculptors and a pioneer of modern sculpture in Lithuania.

5 M. K. Čiurlionis National Art Museum.

6 In 2025 Lithuania marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis. A conversation between Asta Vaičiulytė and Donatas Jankauskas–Duonis (p. 130)

7 Raimundas Malašauskas explains what this rewriting means in his text from 1999: ‘At the time when Andriuškevičius’ original text was written, [Petras] Mazūras was almost the same age as Jankauskas at the time of the rewriting of Andriuškevičius’ text. Not surprisingly, in the process of rewriting, the fragments of the original text that did not need to be altered were of most interest. This stability of the text should be analysed in relation to both the object described and the description.’ Raimundas Malašauskas. “Tapimas ne-savimi,” in Šiaurės Atėnai, April 3, 1999, republished in Alfonsas Andriuškevičius, Lietuvos dailė 1996-2005 (Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla, 2006), 98–101.

8 Audrius Kemežys (1973–2018), Lithuanian cinematographer. Posthumously awarded the Lithuanian National Prize for Culture and Arts in 2018.

9 Sofija Čiurlionienė (n.e Kymantaitė, 1896–1958), wife of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, was a Lithuanian writer, educator, and activist.