At a Loss for Words

My first encounter with a non-heteronormative Lithuanian language was in 2016. And that same year, for the first time ever, I experienced the fragments of everyday life and experiences penetrating into my creative work – fragments too small to be self-sufficient, often seemingly crumbled, possibly distorted, and which I am still connecting together in recreated stories. At that time, I was encouraged to go through my drawers, closets, and journals and pull out what I was living through and what interested me, regardless of my study programme at the Monumental Painting Department. While still a student, I organised the Angry Lesbian Festival, later renamed the Sapfo Festival, but I hadn’t experienced my department as a sufficiently open place where I could eagerly share my marginalised extracurricular activities. That’s when I began to focus on queerified linguistic practices – practices that were not visual enough for the context of visual art, and though they stemmed from my experience as an activist, were also still dubious within the activist world or labelled as ‘pseudo’ – more fantastical than oriented to a specific change or everyday use. When writing the short, fictional story entitled 2017. Jubiliejiniai metai (2017. Anniversary Year)¹, I set out to incorporate linguistic forms that uncompromisingly accommodate non-binary ideas, a language we spoke of as muchanticipated and necessary, but that we didn’t use in daily life.

In the Lithuanian language, people, objects, and adjectives are usually either masculine or feminine, with a few rare exceptions, and the plural pronoun ‘they’, encompassing the two existing genders in the Lithuanian language, is in the neutral/universal masculine form. But as much as we may wish it to be, the masculine gender is not neutral; the masculine gender is masculine. If we were to speak about a hall full of women with just one man sitting among them, in standard Lithuanian we (for now) would use the masculine gender. Thus, the often-used direct translation from the non-binary singular English pronoun ‘they’ has probably (and for good reason) failed to meet my (and others’) expectations.

Lately, and increasingly, especially in the queer community, people can no longer be oblivious to how they address or talk about another person, even when that person is not around. While living in Denmark for the past five years, I have had the chance to experience and observe how the pronoun ‘they’, used in my English speaking environment, gradually became not only common, but also convenient. In a respectful environment, even the unintentional use of an undesired pronoun has become a basic marker of habit; conversation partners correct themselves and carry on talking. It has indeed become very common to ask by which pronoun someone would prefer to be addressed. But in the Lithuanian language change is progressing slowly, and gender-identifying pronouns are difficult to avoid, and there is no general consensus on what to use. And this could indeed be seen as a problem – or perhaps it’s just the beginning of something?

While writing 2017. Anniversary Year I met Gina Dau, who was actively working in linguistics at the time. In 2015 and 2016, Gina and several members of the Lithuanian Gay League conducted an experiment in the use of a neutral linguistic gender and proposed a new, non-genderidentifying pronoun conjugation. After completing my text, using the proposal made by Gina and the others, I understood that the experiment and the proposed conjugation was clearly valuable, but that as a linguistic solution it had little chance of success. According to Gina herself, the new linguistic gender ‘was too complicated and different to fit organically within the language system’². As I wrote, I encountered difficulties that impaired the creative process at nearly every step and, probably much like Gina, I gradually lost all hope that the Lithuanian language could be flexible enough for new signs and universally unrecognised (or unrecognisable) meanings to blend into everyday speech. Looking back, I think that innovations that appear before they’re taken up by everyday users lose the ability to adapt over time due to their inactive usage, and fail to become familiar to the ear and thereby usable. Another side to this situation is that as vocabulary expands and new words appear, language users acquire words to name previously unnamed identities and sometimes even identify themselves with them.

It would seem logical that the users of a language would be the first to develop and create it, but in Lithuania the situation is a bit different. Philosopher and literary scholar Nijolė Keršytė has written that ‘In most countries, standardised language developed on the basis of the language (dialect) spoken by the classes possessing symbolic and/or political power. Put another way, before it became standardised, the language was used by a privileged class. But the specifics of the Lithuanian language are that the privileges for this language were not acquired by any particular language users – not by the cultural, religious, or political elite (writers, clergymen, state officials, or at least the inhabitants of the country’s capital), as in most Western Europe countries – but by the experts in that language, its linguists.’³ I’m certainly not suggesting that language policy should be directly inspired by the practices of Western European countries and that the Lithuanian language should be shaped by an elite. Rather, contrary to this idea, I hope that the power to shape and create the language will be possessed by people who are literally at a loss for words, and that they will create those new words and no one will correct them.

I would say that a non-heteronormative Lithuanian language is currently experiencing an active upheaval. There is no single consensus, but precisely at this moment, many different options for addressing or speaking about another person without identifying one of the two normative genders have been created, and the need seems only to be growing. Now might appear to be the darkest hour, with dawn just about to break, and we will very soon know how to speak ethically. At the same time, until there is agreement on how to name certain things, the debate about terms and meanings remains open. It is for this reason, and due to basic linguistic differences between Lithuanian and English, that I don’t feel it is worth being satisfied with a poor translation of ‘they’. But it is even less beneficial to wait for linguists to come and regulate a non-heteronormative Lithuanian language, as if only then all will become clear to everyone.

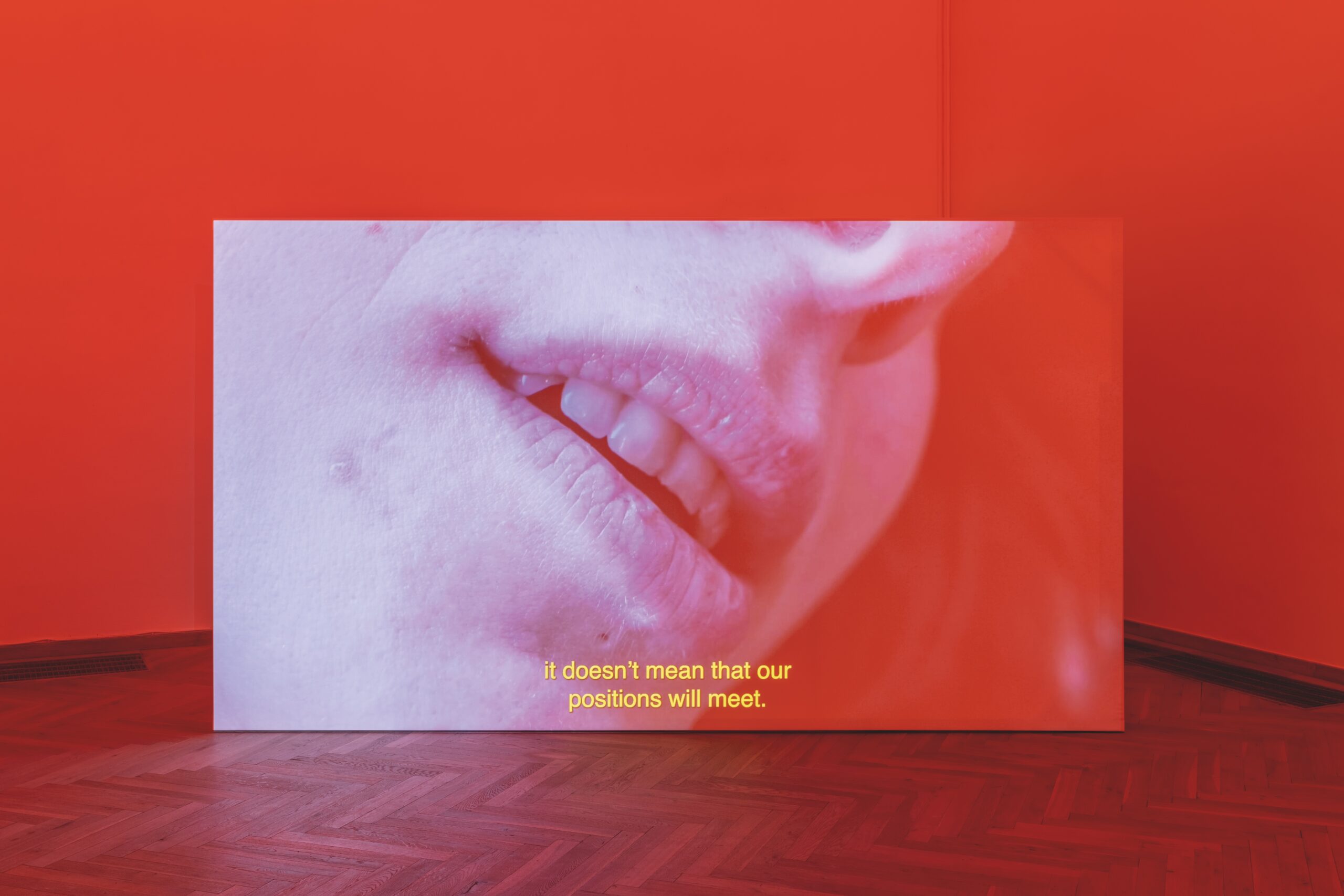

Being away from everyday Vilnius life over the past few years, I observed what was happening in the context of Lithuanian linguistics from a distance. At the same time, in my small ten-square-metre apartment in Copenhagen, I imagined a Lithuanian language for the future. My dreams were not just passive ones: for my texts written from a feminine or neutral gender perspective as universal ones, I’ve been creating gender neutral pronouns, adjectives, and equivalents for professions. In video works created in recent years, such as Daring Dreams/Ateitys Ateis and Skambutis iš ateities (Call from the Future), I included new words which I may not yet use on a daily basis, but which are used regularly by the protagonists in an imagined future. What’s the point of all this? To hear and to see, and no longer be able to unhear and unsee.

While writing this text, I spoke with one of the authors of the Vilnius University Guidelines for Gender-Sensitive Language, Professor Natalija Arlauskaitė. According to her, ‘respect has a political dimension, because respect is seeing, and seeing is political – accepting certain subjectivities.’⁴ I couldn’t agree more. For me, a non-heteronormative Lithuanian language is primarily about etiquette and a space left for the unknown, where my own socio-culturally shaped knowledge remains open to change. To not identify another person’s gender before asking which would be truly preferred, is to refuse to independently judge another person’s gender, to refuse to see gender as a particularly important piece of information, so that whenever it is used, the pronoun (and even the adjective in the Lithuanian language) should be identified. So, in my world, non-heteronormative language is, in principle, a gender-decentralised language. As a creator, I simply use the privilege of creating in, and creating that language.

Agnė Jokšė currently works between Vilnius and Copenhagen. She holds an MFA from the Royal Danish Academy of Visual Arts and a BA in Monumental Painting from the Vilnius Academy of Arts. Using the tools typical of autoethnography, Jokšė tells stories in which the artist’s experiences and past events related to contemplations of love, intimacy and friendship intertwine with imaginative reflections on the world. She works with writing, video and performance, investigating questions surrounding parallel histories, compassion, entangled relations, queerness, and language. Recent projects include presentations at Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen (2022); Artists’ Film International, Whitechapel Gallery, London (2021); Baltic Triennial 14, Vilnius (2021); Publics, Helsinki (2021); NAC, Nida (2021); Mimosa House, London (2020); and the Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius (2020). Her work Dear Friend was awarded the JCDecaux Emerging Artist Award in 2019.

1

2017 – Anniversary Year, is a short story about an alternative world artificially formed on the territory of Lithuania: a closed, post-gender community celebrating the 100th anniversary of a decree published in 1917 when Soviet Russia decriminalised homosexual love. The community has distinct customs and laws, for example only permitting the use in everyday speech of a non-heteronormative language. Those who refuse to follow the rules are archaically and primitively segregated and left to survive on their own in the forests of Dzūkija.

2

Gina Dau, „Vargas dėl giminės“, 2018, Šiaurės Atėnai

3

Nijolė Keršytė, „Kalba – disciplinarinės galios ir žinojimo taikinys“, knygoje „Lietuvių kalbos ideologija“, Naujasis židinys-Aidai, Vilnius, 66 psl., 2016

4

From a Zoom discussion with Natalija Arlauskaitė, Vilnius, 2022