Brutal Poetics of dizzinformation

0. ABSTRACT. HIGH ON LETTERS / ALTERNATED EXISTENZES

While the art world has, for some time already, been talking about the urgency to create new visions and vocabularies for non-discriminative and all-inclusive worlds in the current climate of ecological and other disasters, colonial and imperial thinking is expanding its own brutal, chauvinistic and retrograde regimes. Let’s analyse a few aspects of the brutal poetics of dizzinformation that accompanied Russia’s military intervention in Ukraine.

1. CONSTRUCTING ALTERNATIVE REALITIES

In March 2022, the writer and regional expert Peter Pomeranzev who has extensively written on how Russia is using the media as an extension of its military power tweeted a popular joke in Moscow pro-Putin circles:

Two Russian soldiers are drinking champagne in Russian-occupied Paris, the whole of Europe conquered. ‘Did you hear?’ one smiles to the other. ‘We lost the information war.’

While not forgetting that the joke is just a joke it also isn’t. We should not be naive in regarding its imperialistic fantasy and how easily and with a typical Russian bravado it transforms what at that moment seemed to be the failure of Russian propaganda into an imaginary military victory. In this way, the joke is propaganda par excellence as it camouflages itself as a silly gag while at the same it continues and expands the Russian propaganda machinery. It uses a popular format of a joke, something we all seemingly enjoy and do not instantly suspect the copyright of the Russian psychological warfare agency to be behind. To continue, it reinterprets the status of the information war – suddenly a failure appears to be a victory. It finally fulfils the wet – pun intended – Putinist dream about Russia from one ocean to another, from Lisbon to Vladivostok. The only thing you, the subject of this dizzinformation, must do is relax, stop being critical, and support Putin and the troops by becoming just another disciplined body-brick in the building of this zombified society.

2. ‘GENUINELY POLITICALLY ENGAGED PERSONS AS Z-MEN’

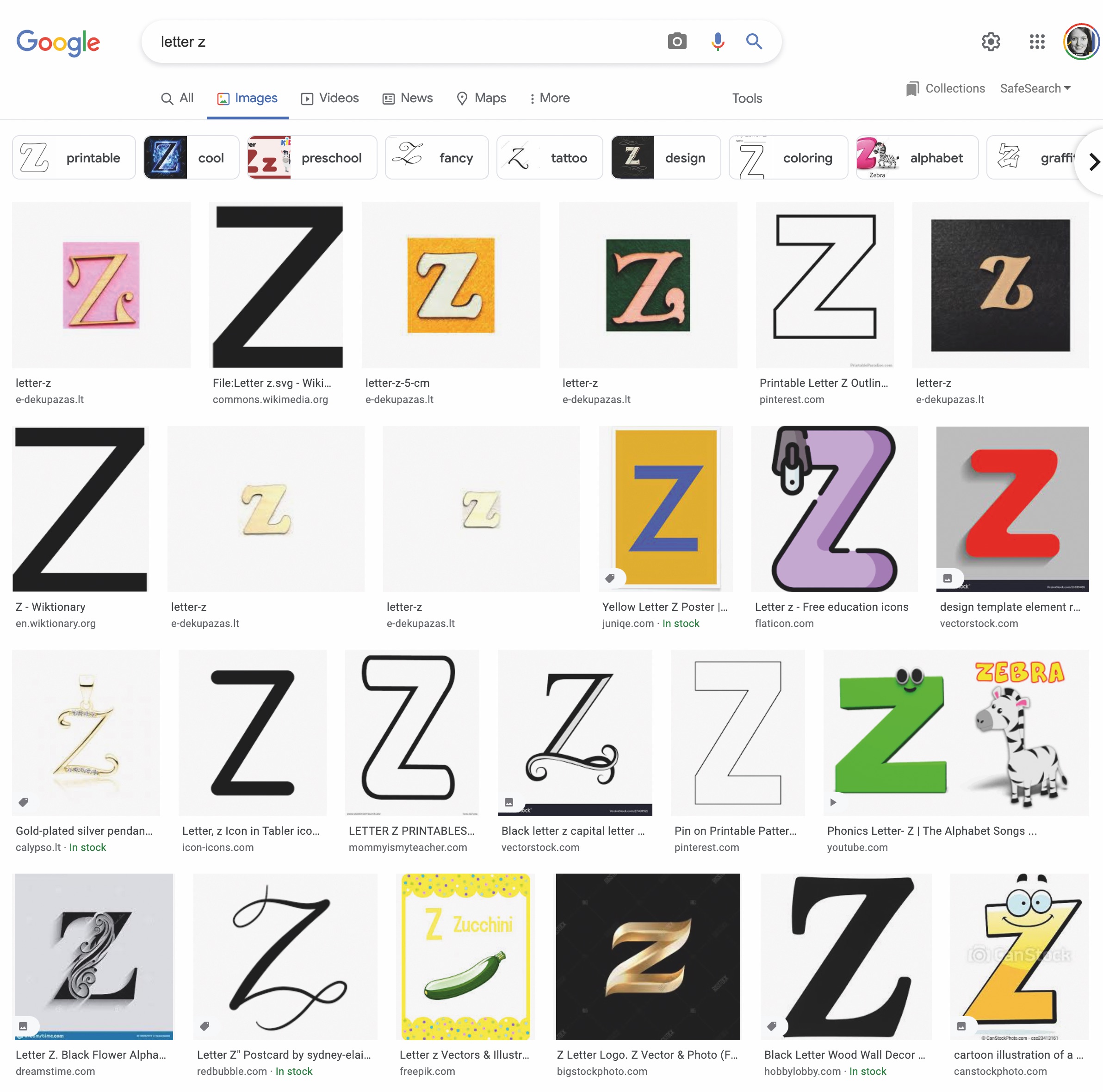

As Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 was preceded and enforced by massive disinformation campaigns of psychological warfare, we started seeing military machines with the letters Z, V and O moving into Ukraine. Over the course of a week or so, various propaganda media campaigns included the letters that started mushrooming through Russia on t-shirts, headbands, cars and buildings to support the ‘special military operation’ as the Russian government officially called it.

Very soon, Russia turned into RuZZia while adopting fascist ideas under Vladolf Putler’s guidance. The meaning of Z, V and O were never definitive. They could stand for Western (Zapad), Eastern (Vostok) and other Russian military regions (according to some researchers O stood for Belarus while others mentioned Chechnya). Z also became Za (for) in support of ‘the special military operation’. The word ‘war’, however, was forbidden – people were even arrested for holding a sign with ‘wo words’ written on it or an obvious book title by Tolstoy.

3. ‘A GENUINELY POLITICALLY ENGAGED PERSON’

You have most probably heard about troll factories that are spreading Russian pro-war lies online, right? One of the trolls’ tasks is to make this kind of propaganda look as if a genuinely politically engaged person created it so the post, as the joke, seems a natural continuation of what the people want.

Let’s go back in time for a while. Around 2015, Lyudmila Savchuk, an investigative journalist and internet disinformation activist went undercover to expose the Russian troll factory Internet Research Agency (IRA), located in Saint Petersburg. The agency employs fake accounts registered on major social networking sites, comment sections, discussion boards, online newspaper sites, and video hosting services to promote the Kremlin’s interests. The point is to weave propaganda seamlessly into what appear to be the nonpolitical musings of everyday people. This is how she described her job:

‘One could say that the trolls’ main task is to give what they write a human touch – write it so there seems to be a genuine politically engaged person sitting at the screen. For example, I was told at the start that I should write something like “I was in my kitchen baking, and I was thinking how Putin is doing a really good job.”… You might write from a fake profile as an ordinary woman that “I would like to meet a good man, someone like Sergei Shoigu” – and then mention how great it was that he had just ordered new fighter planes.’¹

After she anonymously gave the material about the troll farm to newspapers, the trolls proclaimed that ‘no troll factories exist’ and ‘that they are all fabrications by paid-journalists.’ Savchuk then went public and gave dozens of interviews and talks across the world. The trolls turned on her.

According to Peter Pomerantsev in This Is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War against Reality (2019), ‘There were comments and posts claiming she was a sexual deviant, a spy, a traitor. There were phone calls to her relatives saying that people were often killed for what she had done.’ But among the general public, instead of an outcry, she found that many people, including fellow activists, just shrugged at the revelations. This horrified her even more. At one point she began to get anxiety attacks and went to see a psychotherapist. The psychotherapist listened to her patiently, nodded and then inquired why she wanted to fight the state this way – was she some kind of paid-for traitor? Lyudmilla, perturbed, visited another doctor. They repeated the same thing. She felt as if the mindset promoted by the troll factory had literally penetrated the country’s subconscious. She had left the confines of the farm – only to find she was enveloped by it everywhere.

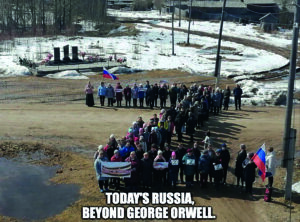

The story is scary on many registers. This is a surrealist Borgesian tale of someone who reveals the truth about some fictional post-truth world, which backfires while fictionalising its discloser. The story is also Kafkaesque. The main character has only the best intentions but falls to an inescapable inner logic: the world knows it is fictional and deceitful but seems to enjoy its fake ideology and detests those who refuse to play by its rules. It’s also an Orwellian story, in that apparently, nothing can be done to change its dark cynicism. Literary allusions aside, this is also a story of how the contemporary world is being created 24/7 by ideological and capitalist mechanisms. Although its secrets are revealed and widely known, nothing changes.

In other words, in Russia individuals and people, in general, are seen as automated, manipulated and programmable beings. In the case of the Russian intervention in Ukraine, the fascist ideology merged with Orwellian doublespeak, the Kafkaesque logic of deceit, the Borgesian methodology of creating alternate realities, and Foucauldian biopolitics.

4. ACTIVE MEASURES

In this context, it is vital to understand the definition of Psychological warfare or PSYWAR which has been known by many other names or terms, including Active Measures (Russian: активные мероприятия), Psy Ops, political warfare, ‘Hearts and Minds’, and propaganda. The word describes ‘any action practised mainly by psychological methods to evoke a planned psychological reaction in other people’² and is ‘supported by such military, economic, or political measures as may be required.’³

According to Pomeranzev, Russia has used information warfare to achieve its aims much more than any other authoritarian regime. ‘If the previous format was 80 per cent violence and 20 per cent propaganda, this regime has reversed that into 80 per cent propaganda and 20 per cent violence. Stalin had to arrest 30,000 people for intimidating the population, whereas Putin can arrest one oligarch and spread as much terror.’⁴

As one of the leading specialists on Russian military strategy in the world, Jānis Bērziņš focuses his work on the juxtaposition of the hybrid and conventional aspects of warfare, such as influence, information, and psychological operations.⁵

According to him, ‘the Russian view of modern warfare is based on the idea that the main battlespace is the mind and, as a result, new-generation wars are to be dominated by information and psychological warfare, … morally and psychologically depressing the enemy’s armed forces personnel and civil population. The main objective is to reduce the necessity for deploying hard military power to the minimum necessary.’⁶

‘I don’t think I have ever seen a country convince its citizens of such an alternative reality as Russia is now doing,’⁷ says Peter Pomeranzev. The Russians see Active Measures as the central part of their warfare which is meant to demoralise, divide and conquer, split society and create a permanent information war.

5. OPERATION CTRL+Z. WILL WE BE ABLE TO DEZOMBIFY THE ALPHABET (AND THE BRAIN)?

There is no easy answer and let’s not pretend we have one as the war and disinformation continue. However, the need to denaZify and deZombify the minds and alphabet remain urgent.

Since the letter Z, which does not exist in the Cyrillic Russian alphabet, became the symbol of the pro war stance in Russia, and because Russian media and social media accounts that stand for the invasion often put Z in their names or logos, a few EU countries banned the public display of Russian military symbols formed by the letters Z and V. Russian social media trolls reacted by making new memes suggesting that banning the alphabet is not the way to go since countries using Latin will have to ban the whole Latin alphabet.

A couple of years before the war, I chatted with Marcos Lutyens, an artist and hypnotist, about the need to create a new language and go to pre-language states, among other things8. According to him, before language even starts to express itself, the opportunity of experimenting in the mental areas before verbal communication presents us with the possibility of understanding things in very different ways, perhaps more fundamental ways, or conversely more unexplored ways. It seems that people will need to find a safe place to seek their agency and cut loose from the needle of disinformation. Marcos described the ultimate place of the shelter being perhaps in the cavity, or ‘cave’ of your mouth, out of which a weaving together of words may emanate to create an imaginary dwelling. And with all the dizzinformation around us, we must explore entirely new ways of thinking, he continued. Words, ideas and actions alone, using old thought patterns will not be enough.

Following Marcos’ thoughts, Operation CTRL+Z will most probably take place by decolonising the psychological warfare and one’s imagination by giving back the agency to the people to create new realities, and vocabularies that are non-discriminative and generate all-inclusive worlds. With certain scepticism to a vast amount of ideological content, it seems that people are fighting back the disinformation with creative articulations, symbols, and memes more actively than ever before. However, the main battles, as always, are still waiting in the near present.

Valentinas Klimašauskas is a curator and writer. Together with João Laia he curated ‘The Endless Frontier’, the 14th Baltic Triennial at CAC Vilnius (2021). With Inga Lāce he curated ‘Saules Suns’, a solo exhibition by Daiga Grantina for the Latvian Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale (2019). Currently, he is the curator at large at Springs.video, a moving image streaming platform that also serves as an educational and curatorial archive and curates an exhibition programme at Nemuno 7, Zapyškis.

Other recently curated projects include ‘An Incomplete & Unreliable Guide to Social Media War Room’ at Georg Kargl Gallery, Vienna (2021); ‘Máscaras’ at Galeria Municipal do Porto (with João Laia); ‘The Cave & the Garden’ at Futura CCA, Prague (2020); ‘Columnists’ at Editorial, Vilnius (2019); ‘Somewhere in between. Contemporary art scenes’ in Europe at BOZAR, Brussels (2018); ‘Portals or location scouting in Kaunas’, presented by Spike Art Quarterly (2017); ‘A hat trick or a theory of the plankton’, Podium, Oslo and Sodų 4, Vilnius (2016); ‘a cab’, Kunsthalle Athena, Athens, and Podium, Oslo (2015). He is the author of Oh, My Darling & Other Rants (The Baltic Notebooks of Anthony Blunt, 2018), Polygon (Six Chairs Books, 2018), and B (Torpedo Press, 2014).

1 Lyudmila Savchuk, ‘My Life as a Troll: Lyudmila Savchuk’s Story,’ 2017, available at https://www.diis.dk/en/ my-life-as-a-troll-lyudmila-savchuk-s-story

2 Szunyogh, Béla (1955). Psychological warfare; an introduction to ideological propaganda and the techniques of psychological warfare. United States: William-Frederick Press. p. 13.

3 https://www.britannica.com/topic/psychological-warfare

4 https://iwpr.net/global-voices/how-russia-fights-its-information-war

5 https://ngwcentre.com/jnis-brzi

6 Berzins, Janis (April 2014). Russia’s New Generation Warfare in Ukraine: Implications for Latvian Defense Policy (PDF) (Report). National Defence Academy of Latvia Center for Security and Strategic Research. pp. 1–13.

7 ‘How Russia Fights its Information War. Interview with Peter Pomeranzev’. The Institute for War & Peace Reporting. 14 January, 2015. https://iwpr.net/global-voices/how-russia-fights-its-information-war

8 On the importance of preverbal communication. A conversation with Marcos Lutyens. December 31, 2020. Available at: https://echogonewrong.com/on-the-importance-of-preverbal-communication-a-conversation-with-marcos-lutyens/