Catharsis of Gaze

As I was driving to meet Jurga, I was thinking about what a privilege it was to have the opportunity to share my thoughts with a philosopher. Jurga studies social relationships, identity, and bodily and emotional vulnerability. Using my body as a container of archival material, I create artwork and as I observe contemporary media channels and ensuing social and political phenomena, I examine how and why non-normative body images are created in society.

During our conversation, and for several days after, I wondered what would happen if we didn’t speak about the subject of vulnerability. What would the world look like if we had the courage to show our weaknesses, which are defined (or shaped) as a negative trait or emotion. But, after all, weakness is just another feeling, mixed in with the rest. Right now, I feel like I’m drinking Coca-Cola every day and I’m on an inexhaustible sugar high.

It once occurred to me that society will only ever change when drivers begin to respect others on the road. Suppressed anger, anxiety, and fears erupt in the rumble of tyres. I myself have noticed that sometimes, when I’m driving, I become like ‘them’. A speeding fine brings me back to reality. It’s pretty simple on the road: always expect the unexpected. In daily life it seems a bit more complicated. It might appear to be the same society out there on the road, but the road is one of those spaces in which there are rules for how to behave. A car becomes a kind of protective shield from the glances or judgments of others. In the end, a car’s make or model might tell you something about the driver or passenger’s social status – but that’s it. Everything else stays inside the car.

I was chatting with a new acquaintance in a bar recently. We were talking about scars on legs, about big scars that, through a doctor’s negligence, become ones we don’t want to see. But back to cars… I drive a VW Passat. According to my new acquaintance, having such a car in Lithuania is also a kind of vulnerability. The make of that particular car is defined as a certain sign of national identity – a ‘construction worker’s car’. In truth, I hesitated before ‘signing up’ up for it. But I bought it nevertheless. And it’s actually a really comfortable car.

It was awfully hot outside.

Jurga Jonutytė: You mentioned scars on legs, and I remember your work Atminties oda (Skin of Memory), which was interesting to me as a refocusing of our gaze when looking at the human body. Can I tell you what it looks like to me? Artists are usually uncomfortable listening to interpretations.

Gabrielė Gervickaitė: I’m always interested in people’s interpretations. I don’t close the door to other perspectives. It’s also a way of interacting with an audience. It’s important for me to share my experience. At the same time, it’s also a kind of activism, revealing suppressed experiences, creating safe spaces (places) for intimate sensations. When I work with a body, when I portray it, it’s important for me to see the whole. I try not to show pain directly, but to transform it. I’m more interested in the form it can create. Even if that is just a small particle in the cosmos.

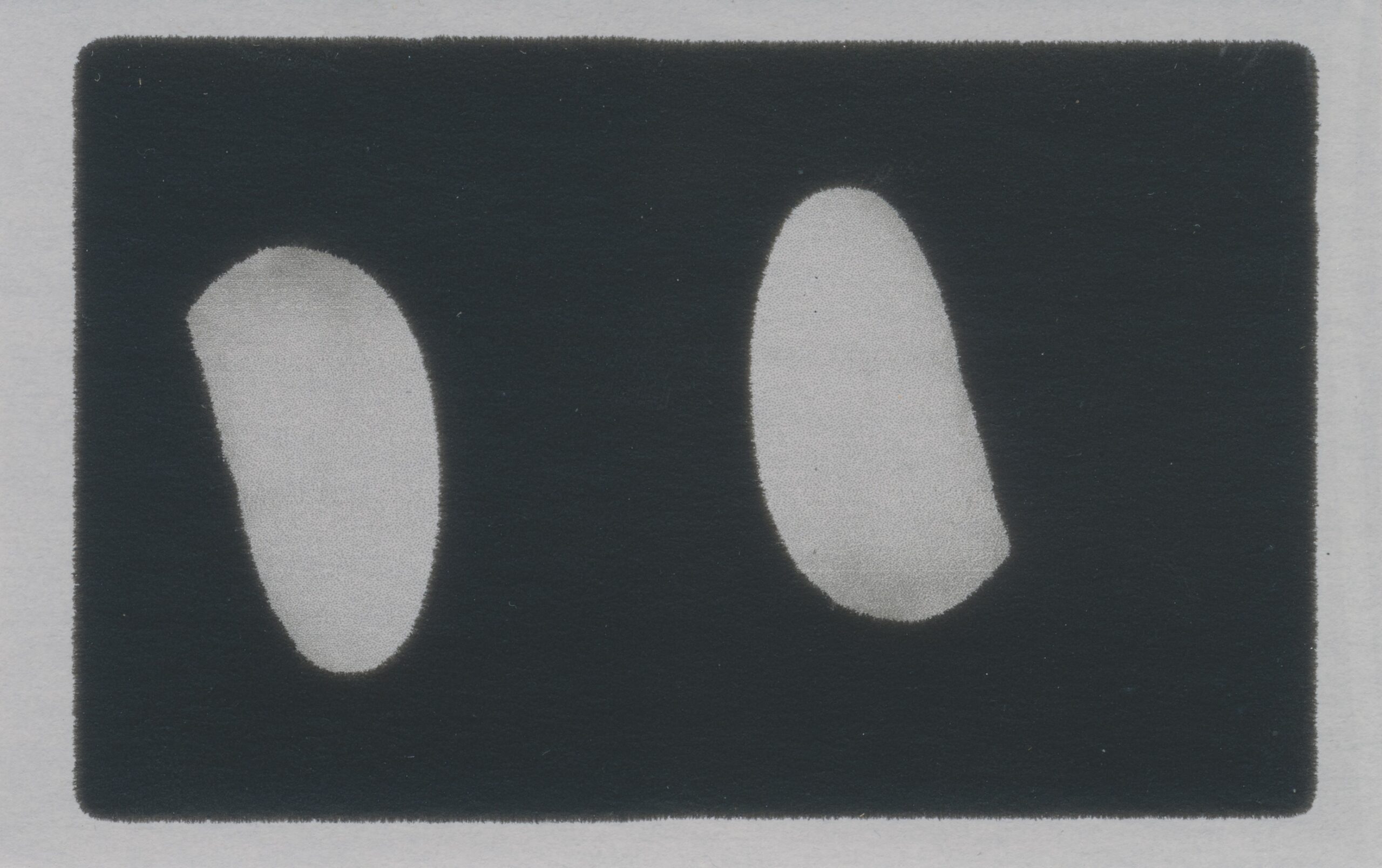

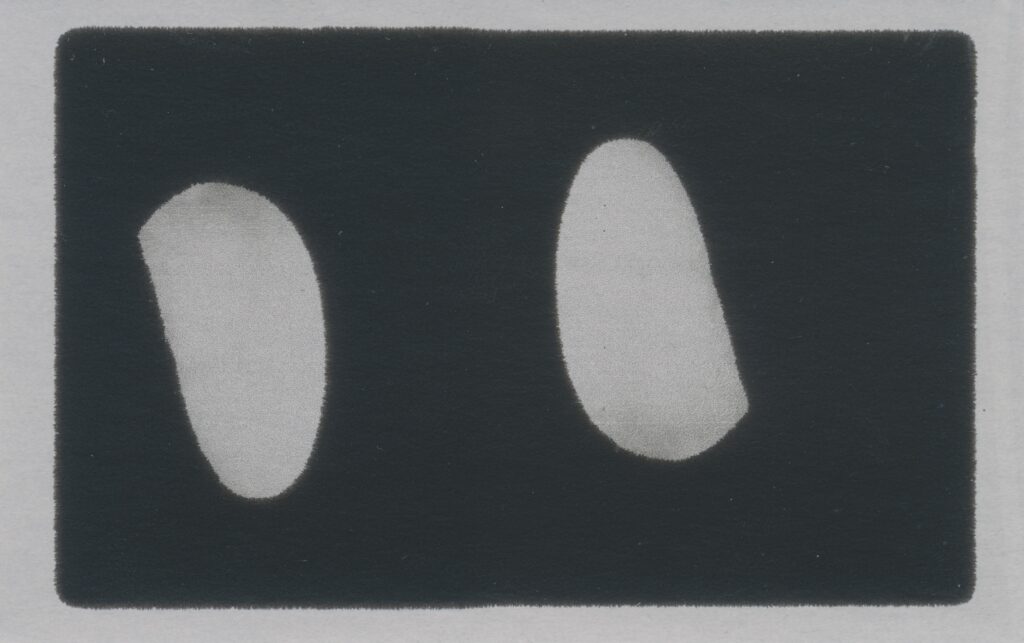

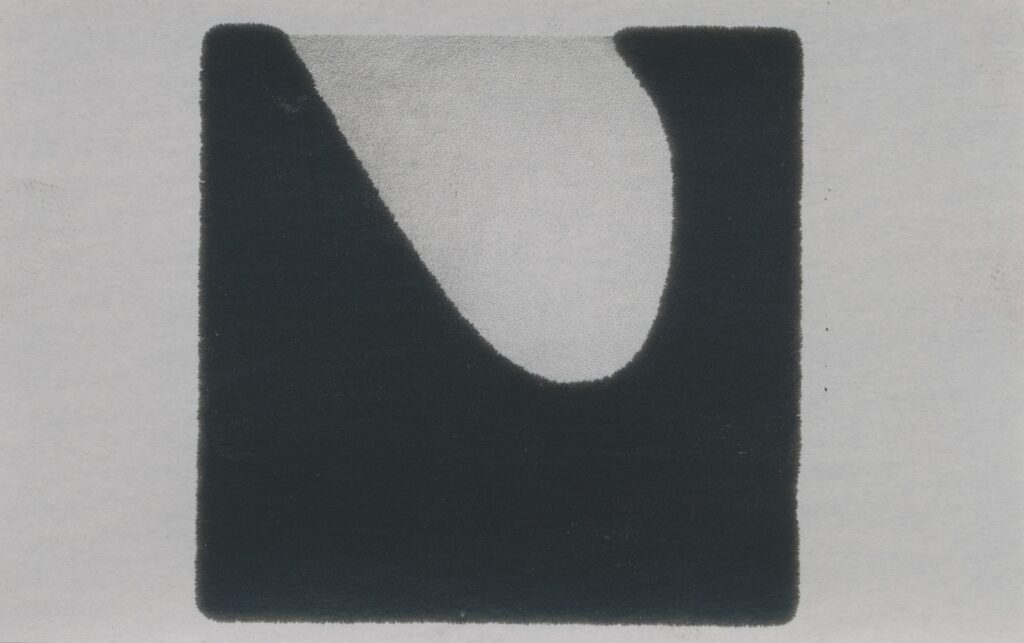

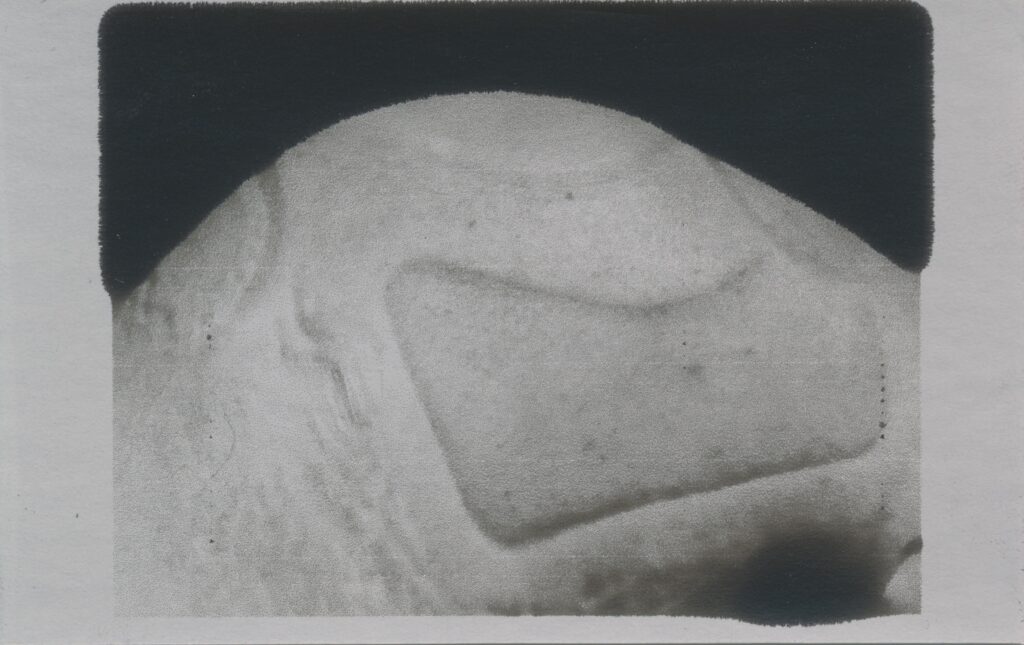

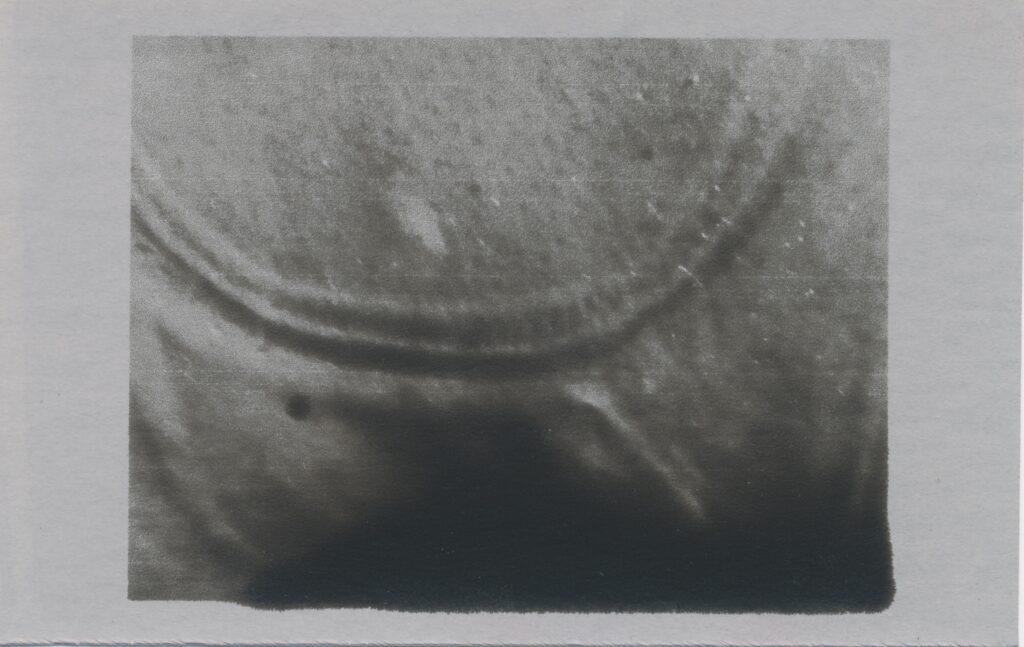

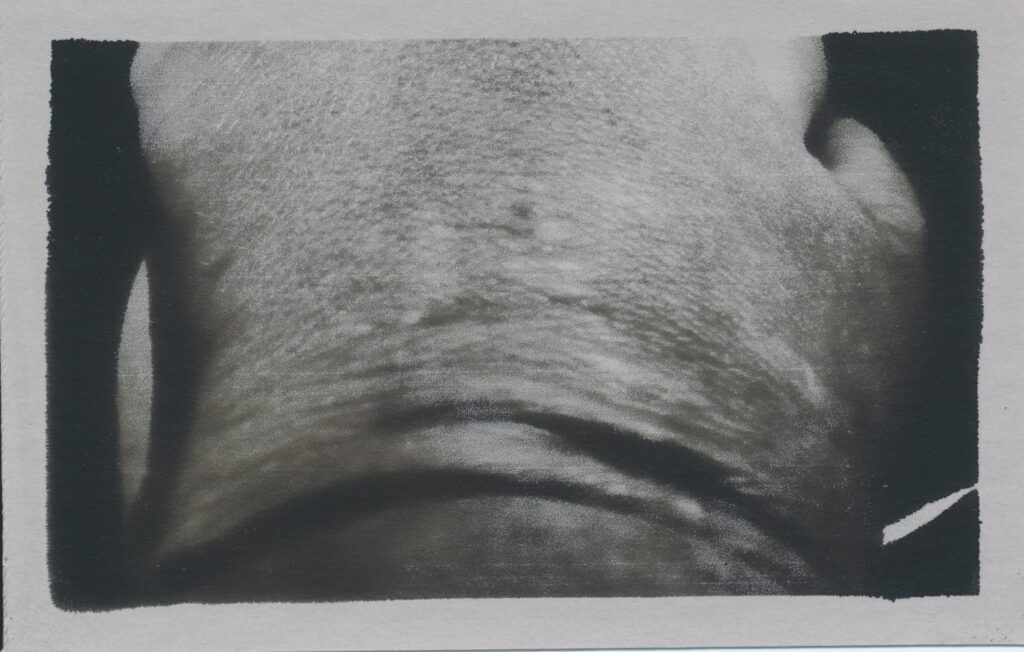

JJ: It’s a change in perspective, of sorts, focusing on the surface of the body, on the texture, on the changed texture or even the texture as it’s changing (because the impressions fade as soon as they’re photographed) and not on the shape or type of body or a part of it, etc. And you get a lot from that. When you look through the texture, and through the shape, through the whole, you begin to see things differently, as boundless, like a substance that is interesting and beautiful in and of itself. And then there’s the human texture: When you look at the surface of a human, like you would the surface of any object, you see how strange it is. If we were to judge it according to traditional concepts of beauty, then it’s one of the strangest and dreariest things. Among animals, perhaps only elephants have such a bleak surface – no fur, no pattern or decoration…

GG : But what skin they have! You’ll insult the elephants!

JJ: That’s what I saw – the skin, human skin. Which is alive, changing, reactive. And that little patch of skin is like a small part of the world that is the human body, a micro picture. One of many substances that create the entirety of that world. And that can tell us more about humans in their surroundings than the whole of an accurately portrayed and complicated human form. Because that form is complicated – with all sorts of growths upon moving lumps.

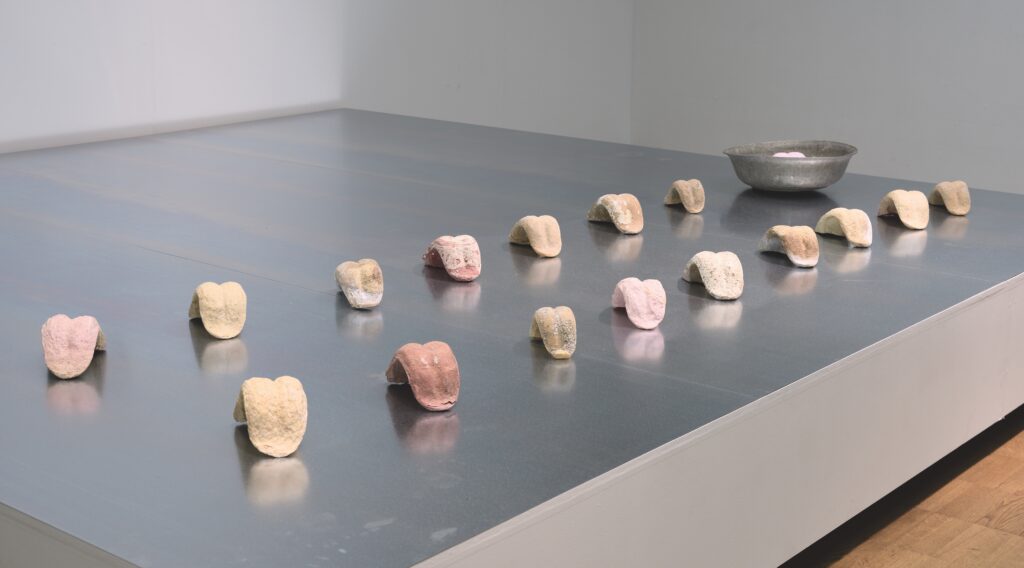

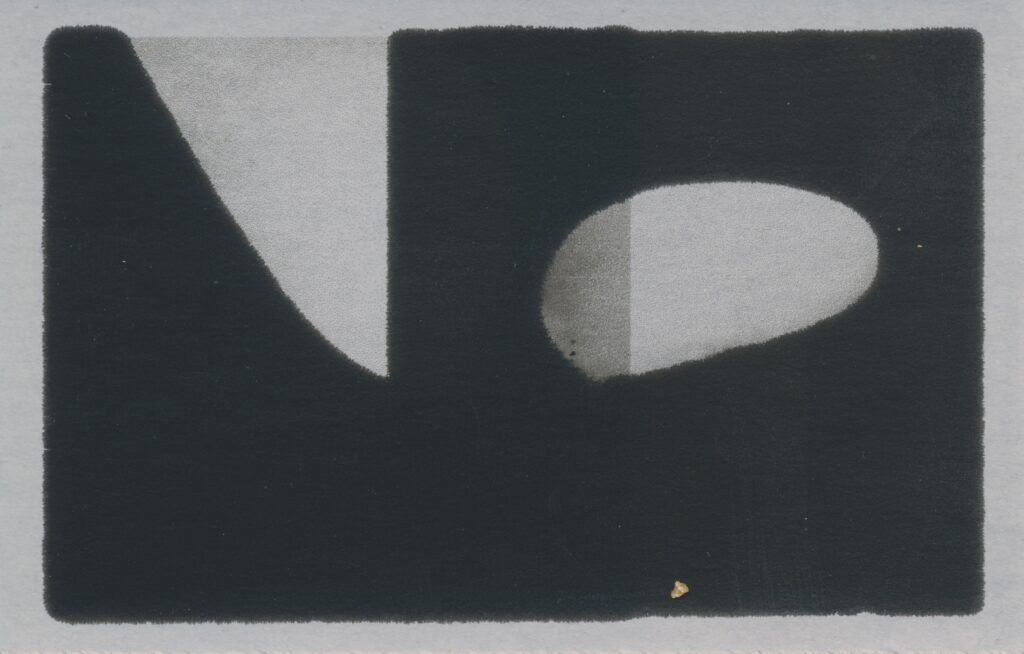

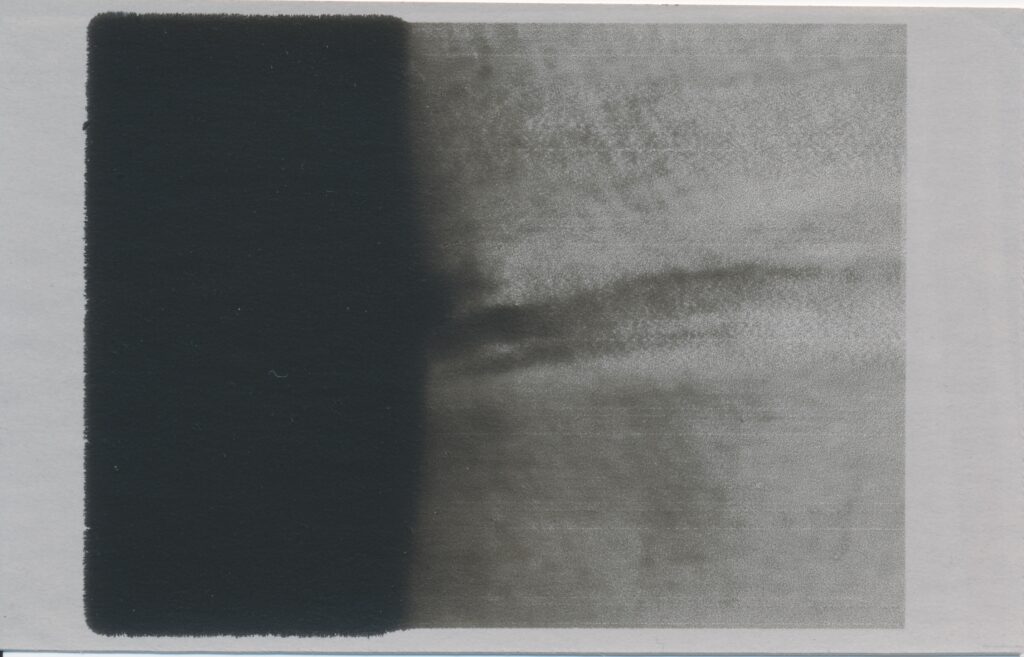

GG : To me, even a tricycle is a complicated form. But, on the other hand, everything is complicated when you begin to explore it, or it can be depending on how complicated you make it. What is the goal – is it to show how complicated something is through its depiction, or how to show that complexity in a simple way? In the creative process, ideas have to go through certain stages and explorations. The photographs I made for Skin of Memory were completely unexpected. I was wearing a brace after an injury, and when I’d take it off, it would leave imprints on my leg for a few seconds. I’d document them when I went to bed. I didn’t look at it as a means of capturing a painful experience, but as a record of a form (a texture, colour, imprint, or mark) that later transformed into small photographs which, like magnified microparticles, added to or neutralised the power of perspective. You can take part in public life, for example, as a victim or as part of the cosmos.

JJ: Yes, the cosmic perspective is more interesting than the victim’s. But even so, a tiny piece of the human body can resonate very differently to just any beautiful texture. The texture of the human skin agitates something in another person’s imagination. If a small section of an elephant’s skin was shown, you’d need an explanation, or at least a bit more of an explanation.

GG : Imagine if I were an elephant. We could do an experiment: is it part of an elephant, or not part of an elephant? But, yes, when you create a particular story, drama is made, and in my case, by highlighting certain aspects of the body, the intimate, and otherness, without excluding them from the whole, but integrating them into that whole in a natural way, without stress. Just as certain details created in my exhibition have become a natural architectural element. For an exhibition at the Artifex Gallery at the Vilnius Academy of Arts, there were several steps that I hid by building a ramp. Most visitors didn’t even notice that it was any different. One of my creative strategies is to say the things I care about in an effective but not a painful way. There has to be an impulse that moves me.

JJ: But the theme of the human body dominates in your work.

GG : Well yes, that which excites and touches me.

JJ: Why, for example, don’t you get an impulse from a blade of grass or a bug, or from other things in the environment? What is it about the human body that is more interesting? I don’t know how you’ll reply, but to me it seems that, when recalling the human body, even as a fragment of the cosmos, or in all kinds of strange spaces, or a body that is painfully broken – in all of those instances we are reminded that the body is not a suit and not a representation of how we are, but that it’s a living thing – strange and interesting. Because the notion of the body as a suit emerges from all kinds of so-called cultural environments. A costume that mustn’t be seen. That’s the point of a proper, neat, pressed, and attractive suit: It shouldn’t be seen; it’s meant to disappear into an orderly crowd. To disappear, you need to maintain your posture, your behaviour, the way you speak, and not stand out too much, to achieve a pleasing yet unobtrusive effect. But the body is not just a suit, apart from its appearance, it also has texture, a softness and hardness, a smell – all the processes that sustain life. And if we were to separate the suit from biology, we would have two areas between which humans would bounce back and forth, like a poor, corporeal being.

GG : That’s what I think – that current political and other processes aspire to such a generalisation and that it’s very powerful. But at the same time, I also experience those niches, where this generalisation is avoided, where a deeper layer is explored.

JJ: I would like to hope so. There should be spaces where generalisations aren’t the goal, and perhaps works of art can try to create or show those kinds of spaces?

GG : I believe that certain intimacies move people – they like them, and that helps me to approach my goal: to reveal without the suit.

JJ: They like them, and maybe it’s also important to remember that you have a body.

GG : Even if it provokes a little distaste…

JJ: That’s also exciting, though.

GG : Touching something that we don’t talk about… It’s also determined by personal experience, of what you can look at and how, what kind of experience is needed and how much, so that you might feel a certain kind of catharsis.

JJ: The way I see it, people have more experiences than they think they do. Very often, those experiences are covered up or erased.

GG : They don’t take the time to experience and feel them.

JJ: They either don’t take the time, or they cut them off as unnecessary or inappropriate.

GG : For example?

JJ: For example, a homosexual experience in childhood. From childhood on, there are very clear norms that govern female and male sexuality, what it should be, at what stage, and what is beyond the norm. That’s the most primitive and most often observed example. But it’s the same with many other experiences: some are correct, others not. From routine things to more existential ones. For example, the experience of killing or torture (killing a living creature is indeed a disgusting bodily experience, and not just a technical act) must be wrong, of course, if an innocent person is being killed. But if it’s not a human, or if it’s a ‘very bad person’, then how do we know – maybe it can also be right? But how can rape, for example, become a right experience? That’s a question that becomes acute during every major war – what does the rapist feel? What can legitimise that kind and scale of violence in a person’s mind? Hatred? Or an order from a commander? And the body just submits to this experience, somehow turning it into a ‘good’ one? But we hear that such submission happens – it’s inconceivable, but it does. The body is obedient and it weighs all those sensations according to the norms practised by the space in which it belongs. And if it is ok according to those norms, then the experiences also become ok. And vice versa: if an experience is not among the ‘right’ ones, then it will be forgotten, erased, as if it never existed. Perhaps not completely erased, only up to the distressing and insomnia-inducing level, but it will not be allowed to be articulated.

GG : But then there has to be a utopian society or a certain group of people with whom you can feel free and recognise it.

JJ: We got onto this subject after one of us mentioned disgust. For example, this is how skin should look. Many women cover up the skin on their face so that nothing is visible: pores, unevenness, pigmentation. Older women, especially, ‘paint’ themselves because they do not deem age to be beautiful.

GG : It’s a way of hiding beneath a layer, or sometimes it’s simply a habit, or a sign. It’s connected to where you are at a particular moment and how you want to appear. You might want to appear like those you associate yourself with. Or use it in the way that animals use camouflage to hide from their enemies. Poisonous plants ‘paint themselves’ in bold colours, like people do to emphasise their sexuality. Some repel, others attract.

JJ: And I feel that it’s also more of a matter of articulation. Just like we have linguistic clichés, we also have visual clichés, and especially in seeing the human body. For example, like how skin should look, or how an arm, leg, hair, mouth, etc. should look. Of course, those standards vary in different social and cultural environments, but they exist virtually everywhere.

GG : If I show my work in Lithuania, I put on certain filters. If I show it abroad, I think less masking is necessary.

I’ve used filters to protect myself, to avoid getting offended. And I also want to protect others. Or that my works would not speak only about me, but that they would be objects recognised by others, of shared experiences. And in that regard, it’s important for me to talk about a certain kind of sharing, of community and creativity, about how we’re able to react and communicate about the things that matter to us.

When I create art, I often think about the viewer, and what might be the best way to ‘send’ the message I’m trying to get across. I don’t want to invite a direct gaze, instead maybe it’s a certain kind of aversion, I don’t want to directly show what hurts or worries me. I want to use artistic means to neutralise and transform it by adding more layers, so even for me, these can seem like filters.

JJ: That’s really interesting, because it seems to me that you’re trying to show the vulnerability of the human body, so that it is not only seen, but also felt.

GG : Vulnerability and sensitivity create spaces in which we can feel like ourselves.

I think that bubbles are especially necessary, particularly right now (at a time of war and pandemic), when people are in confrontation with one another and divided in their opinions, where the subject of Covid is taboo because of the varying opinions and perspectives people have on it. Bubbles are important in social activism.

JJ: Yes, virtual conflicts were particularly active during the pandemic, and probably because of the clash of those bubbles. There is no common society for us all – it’s only a concept. The bubble, as you call it, is my space – I would be more inclined to call it a space. A space where I’m not afraid to be vulnerable. I don’t feel that way in any virtual space – none. Maybe I should, but I haven’t learned how and I’m not going to try. But among the people I interact with, I’m not afraid to be, appear, or feel vulnerable. If I begin to sense that I’m trying to appear ‘tough’ within a particular group of people, if I’m scared of no longer meeting one or another fictional expectation, I withdraw from that circle and try to make sure never to be in it again. Everyone is completely vulnerable – it’s a feature of life. And, in my eyes, works of art that recall that vulnerability help flip that concept from a negative to a positive. Your work does that, too.

GG : If an animal is described as being vulnerable, the meaning of the word is used to signal that it’s in danger of extinction.

JJ: If we finally acknowledged this as one of a human being’s most interesting characteristics, then many things could be resolved on a social level. Today, we’re raised in the spirit of overcoming, enduring, and surviving everything, and not in terms of mutual resonance and togetherness. In that kind of culture of survival, vulnerability has to be concealed, forgotten, or even, as is often said, overcome. It’s still that way for now, but perhaps not for much longer.

GG : It’s a vital function that helps us react, and to understand art. It depends on how much a viewer will allow themselves to be vulnerable.

Jurga Jonutytė is a senior researcher at the Cultural Research Center and an associate professor of the Department of Philosophy at Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania. As a researcher Jurga Jonutytė works on the philosophical reflections of oral narratives (individual life stories or memory narratives) analysing them from the perspectives of phenomenology, post-phenomenology and post-structuralism. Jonutytė has published more than 20 academic publications including three monographs (two of them with a co-author).

Gabrielė Gervickaitė is a member of the Lithuanian Interdisciplinary Artists’ Association and is currently a doctoral candidate in Art at the Vilnius Academy of Arts. In addition to her own artistic practice, Gervickaitė is a curator and works in the field of socially-engaged arts education. She creates artworks using her body as archival material and studies the impact of the construction of normalcy, particularly in contemporary media, social and political situations.

Gervickaitė has received grants from The Lithuanian Council for Culture (2015–2020) and in 2012 was an awardee of the Young Artist Prize, from Klaipeda Culture Communication Center, Lithuania. She has participated in a number of artist’s residencies including CreArt Atelierhaus Salzamt in Linz, Austria (2016) and FLOC (Flowing Connections) residency as part of the Ostrale Biennale in Dresden, (2021). Her work has been shown in various exhibitions in Lithuania and abroad including ‘Pärnu FotoFest’, Pärnu Linnagalerii (2019); INVISIBLE ARTIST. ‘B-galleria, Superb’ festival, Turku (2017); ‘Positions’, Berlin (2018); un/mute, an online residency and international group exhibition for the Austrian Cultural Forum, New York (2021). Her curatorial and socially engaged projects include the exhibition ‘Body Culture (LGBTQ+)’ for the Embassy of Sweden in Vilnius 2016 and the video documentary project ‘CARE, YOU CARE’ with young people inVilnius between 2014 and 2015.