Cormorants in Ancient Woods

Rūgštus miškas, Acid Forest

Can you imagine a tourist attraction where people come to see a dead forest? Where they are not only observers, but also the ones being observed and heard by black cormorant birds? Acid Forest is an ironic creative documentary about an unusual tourist attraction: dying, leafless trees overtaken by thousands of cormorants, impacting the ancient forest with their acid-fortified faeces and causing visitors to reflect on the relationship between humans and nature. ‘Apart from the main storyline, I kept my focus on playful dialogues, illustrating how a range of political questions, historical narratives, migration vectors, and cinematic experiences intervene into the human projections of nature. I hope this helped the environmental paradox of Acid Forest to become a metaphor for the surreal world we live in,’ says the director of the film.

Directed by Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, coauthor and producer: Dovydas Korba.

Sengirė, The Ancient Woods

Filmed in one of the last remaining patches of old-growth forest in Lithuania, The Ancient Woods is a place where the boundaries of time melt and everything that exists neither withers nor ages but ‘grows into’ eternity. This poetic and atypical nature film takes its viewers on an endless journey – from forest thickets to wolf caves and up to a black stork’s nest, and then deep into the water to an underwater forest before returning to the human beings inhabiting the edge of the woodland. There’s no commentary, only the rich, almost palpable sounds of the forest and the magical situations captured by the camera.

Directed by Mindaugas Survila.

Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė:

Did the overarching idea for The Ancient Woods come to you as a concept for a film or as part of a broader strategy?

Mindaugas Survila:

Neither – neither my earlier film, The Field of Magic, or The Ancient Woods arose out of a need for me to justify myself as a director – I just wanted to tell a story. The Field of Magic is a film about people who live next to a landfill and go to work there every day. I filmed them because I just couldn’t believe that such a community existed so close to Vilnius, in this day and age. In part, because I wanted to tell a story, and in part because I wanted to learn about and understand these unique people myself. As for The Ancient Woods, as a biologist I already had enough practical knowledge and information, but my main goal was for people to learn more about old-growth forests and why they should be valued beyond just their monetary worth. It was an ideological shift. What about you? How did you become interested in Acid Forest and how did you begin to construct it?

RB:

My connection to nature is not scientific, but direct and pure. I was never interested in nature films. But since childhood, I used to spend every summer in the forest, by a lake, without electricity – running around barefoot, picking berries and mushrooms. Like an animal. I didn’t have any defined function in nature. Later, in London, I lived on a street where all the trees were bricked in right up to their trunks, their knotted branches cut back. I’d pass by those mutilated, crippled trees every day. That conflict between trees and humans seemed to call out to be explored as a theme, but photographs would not have sufficed. I was studying my MA in screen documentary at Goldsmiths University and I was looking for a subject for my final diploma project. The conflict between the cormorants, trees, and humans in Juodkrantė as a subject for a film came up in a conversation I had with my father – he was the one who brought it to my attention. I started the film as a research project, without knowing too much about the subject in advance. I only heard later that cormorant dung, even though it dries out pine tree roots, is excellent for other plants. Cormorants basically transform the soil. One bird-watching tourist whom I met on the observation platform told me that in Peru, cormorant dung, called guano, has been harvested for fertiliser for over one and half thousand years, since the days of the Inca Empire. There was a time when people were even sentenced to death for disturbing these birds. Ironically, the process is exactly the opposite in Lithuania, where chicks are condemned to death before they’ve even hatched. But, returning to the origins of the film, my desire to explore this subject came from my cinematographic intention, with no ideological ambitions.

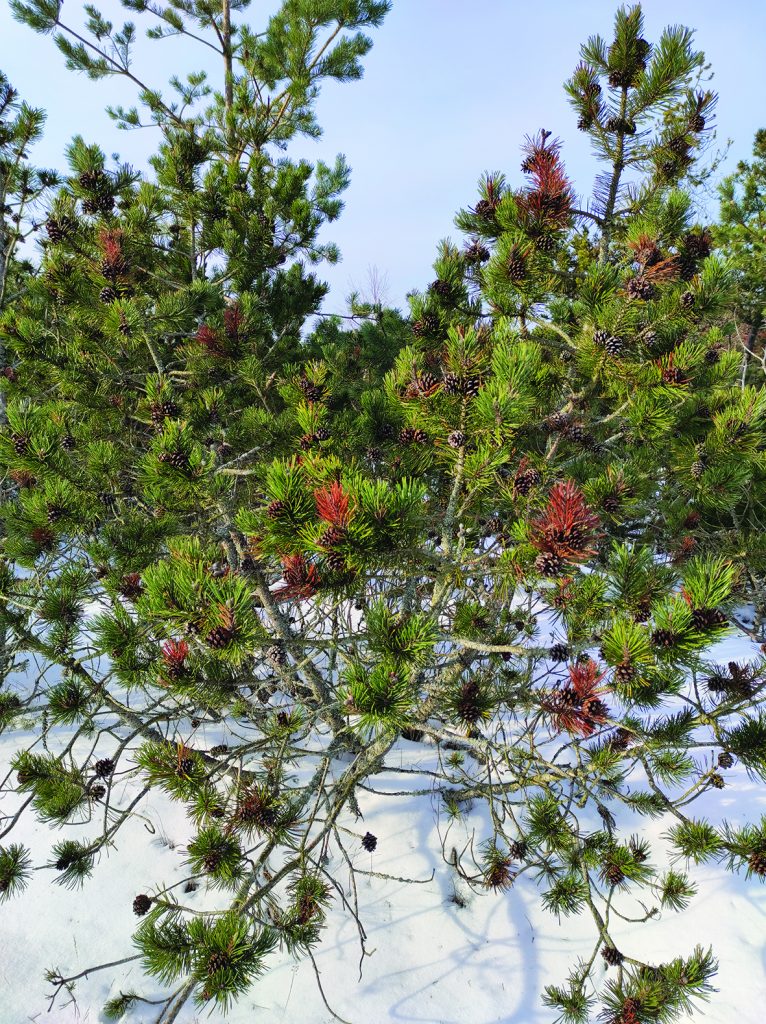

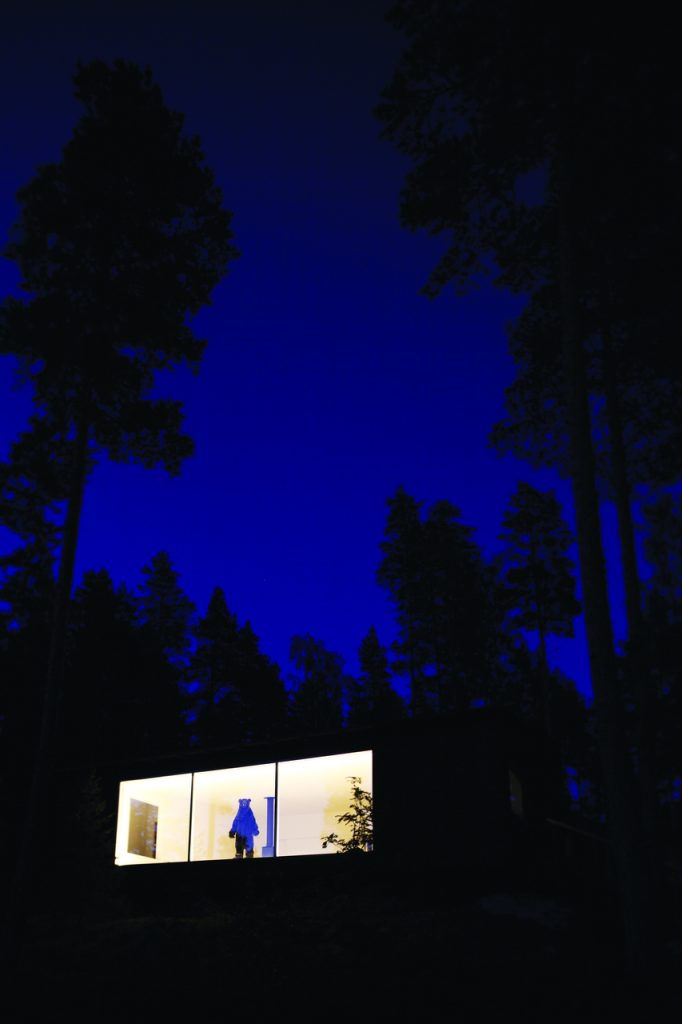

Photo from making of “Rūgštus miškas” (“Acid Forest”), Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė and Dovydas Korba

MS:

People classify feature films as fiction and documentary films as the truth, even though both types are edited, with the focus directed at details chosen by the director. How should we value a film – how much ‘organic truth’ does it contain? Because, in truth, without a point of view imposed by a specific individual, there would just be a security camera, for example, relaying an image – but even then, someone would have to introduce a ‘human hand’ by actually placing the camera in a specific location and pointing it at something. How do you decide, as a percentage say, how much ‘truth’ your film contains?

RB:

That’s a good question.

MS:

Maybe based on the amount of material – how much material has been compiled and how it’s been specifically selected. Then the question also becomes: what was chosen and what didn’t make it into the film?

Photos from making of Rūgštus miškas (Acid Forest), Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė and Dovydas Korba

RB:

Legendary documentary director Frederick Wiseman has a wise phrase mentioned in the book Reality Fictions¹. You construct a documentary film from things filmed in real life, but new meanings are formed through the editing process. I’d be interested to know how much truth you think there is in The Ancient Woods?

MS:

If you walked into the woods, what are the chances that you’d actually see a capercaillie or a Ural owl? Practically none, I think. No forest like the one shown in The Ancient Woods exists in Lithuania. It’s a ‘fairy tale’ created from tiny fragments recorded from a forest. It was 400 hours of material filmed over many years, but the way I see it, I had to work very hard every minute, every second towards that goal – it wasn’t just random imagery. And because of that, I feel like the film is a complete fairy tale.

There’s not a single hint of a ‘randomly placed camera’, because we construct the world we want at that moment.

RB:

But The Ancient Woods focuses quite a bit on nostalgia and a longing for what’s gone, or very nearly gone. It’s very justified, and you couldn’t call it untrue.

MS:

Right, you wouldn’t call it ‘untrue’, but there was a great deal of work put in to convey what had existed before. If I were to make a film (even a feature film) set today, in 2021, then I’d just go out into the street and have wonderful sets for this period. If you’re filming something set in 1923, then building sets would be quite expensive. I had a similar situation with The Ancient Woods: I tried to film how forests used to be (reconstructing tiny sections), and I had to devote a lot of energy to tell a story about something that is almost entirely gone. How much ‘truth’ do you think there is in Acid Forest?

RB:

Not to get totally depressed, but Dovydas and I never actually counted how many terabytes of material we’d filmed, but what we included was about 0.0000th of what we’d filmed. Shooting the tourist observation platform required the most time. The selection process reminded me of sorting through rubbish. It’s good that I had a strategy and I knew in advance what subjects I was interested in – when considering the conflict between people and the trees and birds, I noticed an interesting parallel with social life and politics, and with historical narratives. The decision had been made to control one species of bird because of its specific characteristics, and they’re trying to make sure that this process doesn’t harm any other species – something similar to the principles of ethnic cleansing. But if we tried to talk about that in all seriousness in the film, we’d come off a bit moralistic. Having in mind the parallel we were seeking for, you couldn’t come up with anything better than the survival myth around Hitler’s bunker which appears in the film as a joke. There are also clearly racist parallels in judging the cormorants: someone doesn’t like their black colour, birds are subjected to aesthetic categories and superstitions just like people. The geopolitical angle also comes across quite vividly: American tourists complain about needing a visa to visit Kaliningrad and ask the Russian tourists what rules apply to them. And in the film, all of this is observed and heard by the birds, whose movement and freedom to choose where they want to be is also being restricted. The selection of the material was very deliberate and there were so many different versions during the editing process that it’s clear there’s quite a bit of fiction there, but it’s assembled from the documented gifts we were given.

MS:

That’s the beauty of documentary film: in rare instances, it gives you a gift. And the longer you work, the greater the chance that you’ll receive another gift. As you said, it seems as if everything is so simple, that everything just happened and that you filmed it, but you need a lot of energy to create that impression for your audience.

RB:

Exactly. There’s a Polish director named Paweł Wojtasik. One of his films shows these moving blocks – travelling along so easily and gracefully, like in some wonderful musical symphony, but they’re actually blocks of excrement at a cleaning facility. He says that he refines a project until it appears ‘effortless’ – until you no longer feel any work of the filmmaker at all. Is it easy for you to stop the editing process?

MS:

It would be helpful if there were a strict producer who’d tell you that your time was up. When you’re very demanding of yourself and you want to ‘make it a bit better’ – it’s not easy. But then a festival or some other consideration draws nearer and you’re forced to stop. Maybe people in other crafts, like carpentry, have it easier: you cut your boards, assemble a table, polish and paint it, and that’s it – the work is done, because that’s how the table is supposed to look. But with a film, you might be the only one with a sense of how it’s supposed to be. And you’re not absolutely sure. Many things become so much clearer after some time has passed. And while editing it’s a good thing to take breaks along the way, to give you time to pull back and actually see the real situation.

How did you manage to stop?

RB:

A festival forced me to stop as well. Clearly, to submit an unfinished film to a festival also requires you to reign in your self-criticism. To me it seemed the film still had so many issues, but the premiere suddenly came and I didn’t expect it to be well received – afterwards, we went back to edit a bit more. It’s great when you can distance yourself. Now, I go to the cormorant colony and I’m really glad I don’t have to film anything. And do you continue the same project, just in a different form?

MS:

Old-growth forests are home to 15,000 different species, and I only included 60 in my film. Old-growth woods are the kinds of places you could talk about for the rest of your life. My Lithuanian language teacher Stepas Eitminavičius used to say that some come to know the world by wandering around it, from top to bottom, while others just sit at the far end of a field and watch how a cornflower blooms. It’s a real problem for biologists. If they sit down in the middle of a field, for example, they can’t just enjoy the sun and the wind. They sit there and think about the plants that are there, how they interact, and, given the soil and the plants, about what kind of bugs would live there – it’s all very interconnected. Sometimes I miss the ability to disconnect and go out into the woods and just be, without analysing.

RB:

How are the Ancient Woods thriving in virtual reality following the film? Are they expanding in size or has The Ancient Woods project just changed in format?

MS:

Anyone can enter the Ancient Woods with their browser, and look right and left, up and down, etc. As you turn, the sound follows you. And if you hear a sound that intrigues you, for example, you can click and go into a stump to see how bugs live. If you hear the sound of an owl, you can rise up into the treetops and watch a family of owls. The image and sound quality will be similar to that of the film, but here everyone will create their own script and choose how to spend their time. I hope that about 15% will consist of material already filmed, and the rest will still have to be recorded to build interactivity. For example, if I need to make it possible to look from side to side, then I’ll have to film more general images, so I’d have something to choose from. The sound recording technology is also a bit different. We’re essentially at the hardest stage right now – fundraising. But we’re creating it gradually. We have the equipment and we’re testing it – my brother is doing the programming. There is all this maintenance work. For example, we have to make special nest boxes for filming. People are curious and like to go inside places – especially where it’s harder to get into. So, we’re creating those kinds of spaces where anyone on an interactive platform can explore ‘with one click’ and enjoy an undiscovered world.

RB:

You’re not afraid that the subject might drag on for too long?

MS:

Working as a cameraman for a sports TV channel was good practice for learning how to pan a camera, because a football player and a moose run in a pretty similar way. The Field of Magic was basically just observation. Someone once said that ‘Survila films people like they would be little animals’. To me, that’s a huge compliment. Because imagine if, as we’re talking here, the Pope would walk into the room and say: ‘Keep talking, please continue – pretend I’m not here.’ I don’t doubt that the conversation we were having immediately before would change (no matter how hard we tried not to). The same thing happens when a camera crew arrives at their subject. Very often, films (whether feature or documentary) are a mirror reflection of their director. And while filming The Field of Magic, I felt completely uninteresting compared to my subjects. To me, The Ancient Woods and The Field of Magic are very similar films. The only difference is that, in The Ancient Woods, I went completely unnoticed. But I guess I did edit it together differently to how a thrush might do it. You can still sense the artist’s hand… Oh, well.

People sometimes ask: ‘So, it’s another project about nature – another film like The Ancient Woods?’ I could say the same thing to those who create films about people: ‘So, your second film is also about people, and the third one, too? Don’t you have any other subjects besides people?’ (smiles)

So, nature is very diverse and full of themes. But the problem is that people can only really understand human emotions well. For example, if they see someone crying when they call their son whom they haven’t seen in fifteen years, they immediately feel that emotion. But in The Ancient Woods, when a moose walks through the woods – is it sad or happy? People can’t usually tell anything from a moose’s expression… That’s why it’s hard to create films about nature, to be able to touch your audience through other means.

RB:

We had that same issue with Acid Forest. I remember how my first emotion was empathy for the birds, which is what probably led to us filming them from close up – even though that meant interfering with them a lot more. But in the film you can see the care from very close up: you see how the female and male trade share in the hatching duties, how they warm [the eggs] and remain by them at all costs. Humans can easily recognise the birds’ care and close bond. But people in the film are tiny, like ants in a wide frame. It’s harder to identify with them – we wanted to change the species hierarchy.

MS:

I was driving with a friend and we were talking about films and the future Ancient Woods. He said: ‘Thrushes, for example, don’t create poetry, after all.’ I asked him how he knew that. Because I’ve never walked around a city and seen someone reading poetry in the street. So, couldn’t I also claim that people don’t create poetry? How much effort have people truly made to really listen to a single thrush, every evening, and decide whether it’s poetry or not?

RB:

I remember how different the cormorant sounds were. How they’d launch up and screech in fear when an eagle flew nearby, or how they’d return home to find that crows had eaten their eggs or made the chicks fall out of the nest in fear. I could hear how their voices changed in horror. But when they paired up, the dynamic was entirely different.

MS:

Just like you need to spend time with humans to get to know them, you have to do the same with animals.

RB:

But only a few people bother to do that.

MS:

There’s no point, because there’s no benefit to humans. Everyone allocates their resources and time to different things, in the end. From an evolutionary perspective, for example, people have adapted over a very long time not to see plants. If a bird suddenly moves on a branch, say, then they’ll notice it immediately, but they won’t see the plant, since it’s not going to run away and offers little benefit. That’s why there are many more ornithologists than there are botanists. And natural scientists, when they first start, they very rarely begin with botany and then move on to ornithology. They usually begin with ornithology and then start to develop an interest in other areas.

RB:

Very interesting. But if a plant has a functional benefit, then would it not be noticed sooner?

MS:

Yes, but the first reaction is essentially to movement, because that could mean either food or danger – the human brain needs rapid information. Maybe this explains why film people don’t like to use the actual spring green colour of plants in their films, because it doesn’t convey information – it just exists.

RB:

Interesting. I had thought these were aesthetic convictions – that spring green was too bright.

MS:

Maybe that’s just how I see it, maybe it’s not that either. Going back to your question about editing – that you initially worry about it and want to change something, but then you feel the pressure of a festival. When have you felt that nothing needs changing anymore? Do you not get that feeling now?

RB:

I still do. For example, even now I think it’s really a shame that the trees rustle when the Japanese tourists sigh. In the material, you can hear a beautiful synchronicity in the people’s voices, but in the film the rustling of the trees is perhaps too loud – it hides that beauty. I still think that’s a real shame, but I know that it would cost us a lot to fix that one thing.

MS:

I recently saw The Field of Magic again after many years, and I thought it was a good film. It’s like sitting down in a field to just enjoy its beauty – the blades of grass rustle and all the serious things disappear.

Mindaugas Survila has a MA degree in biology from Vilnius University, and has since been following his childhood dream to make films about what is closest to him – nature. At the end of his graduate studies in Ecology and Environmental Management Mindaugas completed his first film Meeting the Ospreys, which was followed up by the documentary poem The Field of Magic.

Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė is working in the contexts of cinema, performing art and visual art. In her creative practice she often explores the gap between objective and imagined realities and playfully challenges an anthropocentric way of thinking. Her most recent collaborations are the opera-performance Sun & Sea (created with Vaiva Grainytė and Lina Lapelytė) and the creative documentary Acid Forest (created with Dovydas Korba).

- Thomas W. Benson, Carolyn Anderson, Reality Fictions: The Films of Frederick Wiseman, Southern Illinois University Press, 2002