Jonas Mekas as a Poet

- Jonas Mekas films flowers, picture by Antanas Sutkus, Lithuania 1971

Jonas Mekas is known primarily as a filmmaker; not only a filmmaker but a very inventive and innovative creator of a new style of filmmaking: the film diary. However, during his most active and productive years, he was not generally known as a filmmaker at all. His claim to fame throughout the 1960s and 70s was as editor-in-chief of the first significant magazine for independent film in the United States, Film Culture, and for writing a regular film column for the Village Voice. He was considered a publisher and a film critic and an ardent supporter of alternative film and filmmakers. He barely spoke English when he started the magazine in 1954.

In New York in 1963, Jonas started a screening series called the Film-Makers’ Showcase (later the Film Makers’ Cinematheque) and he became known as a film curator, or programmer. He founded the Film Makers’ Cooperative in 1962 and Anthology Film Archives in 1970 and thereafter became known as an organiser and activist for the avant-garde film movement, for its distribution and preservation. Although he continued shooting and editing his films on a daily basis, this activity was relegated to the brief moments and nights he could spend in between the busy schedule of managing all his activities in service of the avant-garde.

Later in life, Jonas devoted himself exclusively to his filmmaking and art installations, achieving great success at a late age. His art career developed when he was in his 80s, with exhibitions in major museums such as Centre Pompidou and the Serpentine Gallery, and an exhibition at the first Lithuanian Pavilion of the Venice Biennale. Finally, Jonas became known around the world as a filmmaker, in the last 15 years of his long life.

However, any Lithuanian could tell you that Jonas Mekas was first, foremost and always a poet. He published his first poetry book in the Lithuanian language at the age of 25, long before arriving in New York, before ever considering making movies. He continued to publish many books of poetry, alongside his writings on film, his diaries, his manifestos, and even some plays and prose. Poetry is the base and basis for all his subsequent work.

When pressed on the qualities of poetry he found important, Jonas explained that, although different poets have different sensibilities and work with different content, poetry ‘catches something essential in a very, very condensed and intense way. The intensity and condensation of reality, feelings and emotions – everything comes together. In form, and of course the language.’¹ When observing Jonas’ filmmaking style, one can see this same attention to the intensity of experience, condensing time, shooting frame by frame, capturing instants and transforming them into bursts of light and colour.

- Film still from Walden by Jonas Mekas, 1969 © Jonas Mekas Studio, courtesy of Re:Voir

- Film still from Walden by Jonas Mekas, 1969 © Jonas Mekas Studio, courtesy of Re:Voir

Jonas Mekas’ poetry and poetic sensibility informs all of his work. His films, videos, photos and writings are not works of conceptual art; they are direct observations, made in the here and now, moments of life being lived, sometimes poetic, sometimes mundane, mostly joyful though often tinged by the memories of lost childhood, as seen from exile.² So-called experimental techniques are scattered throughout his cinema – superimpositions, blurry shots, images rushing by because they were shot frame by frame – but these are not experiments in the scientific sense. These are poetic effects that represent best how a moment is really lived, perceived and remembered. Images do rush by. Memories are blurry and overlap. Moods weave together. The real world meets the brain and becomes a flurry of light and motion.

Jonas’ early Lithuanian poetry captures glimpses of life in exactly this way: details, textures, bright flashes of colour, glimpses of nature and people overlapping, words gliding together. Consider this twelfth poem from Idylls of Semeniskiai³ (Kassel, 1948):

In woods and thickets, across flowering fields

the women go picking berries:

their kerchiefs a bright flock

against the black, mud-clotted barrens,

dark alder shrubs and buckthorn,

willow and dogwood shade.

And when they get through the last

Mud-blind, wreck-tossed ditches,

the fields are right there before them,

reaching far out of sight, green

all the way to the gray moss-backed cottages,

the orchard trees and even taller

birchtops and pale sweeps.

And right up to the stumps in the hoof-tracked paddock,

and the gaping clay-plugged siding,

run bean fields, oat fields

and flax, more than an eyeful, so blinding blue:

blue as can be!

Slim fieldpaths, green hedges

guide them home,

with blossoming graindrills, cornflowers, gold

wild-radish and tansies at their feet,

clusters of thyme in heaven’s own blue,

the boundary stones pale

in the hot sun,

fields of red clover stuck over with bees,

and the peas twining and climbing

in long, yellow streams.

All of Jonas Mekas’ poetry and films spring out of his voracious curiosity, his power of observation, his love of nature, his thirst for culture, his powerful memory and his itch to chronicle the passing of time, coupled with the cruel fate that the twentieth century brought upon him – the Second World War, which forever separated him from his family, his country, and even his language.

Jonas himself told the following funny story about his history with languages:

I grew up in Lithuania in a small village that had its own dialect. When I began going to primary school I had to learn the official Lithuanian language. When I went to the gymnasium I had to learn French and Latin. Then the Russians, the Soviets, came into Lithuania and said: French is no good, Latin is no good, Russian is good. So I had to learn Russian. A year later, the Germans came, and the Germans said: Russian is no good, German is good; so I began learning German. Then I ended up in the forced labour camp in Germany and I was with the war prisoners, the Italian and French war prisoners, so I said to myself it’s a good occasion to learn Italian. Then the Italian capitano told me that the language the rest of the Italians were speaking was Sicilian and he didn’t even understand it himself. So I said at least I can improve my German, but then I learned that the German they spoke around Hamburg was plattdeutsch that even some Germans do not understand. Then the war ends and the Americans come. So I learned to speak English. But by that time I had enough of languages. So I said, now I will learn the language of cinema, an international language, I can talk to everybody! So I come to New York, I get my camera, I meet other friends who run around with Bolexes and make films and we show our films, and people say, ‘What are you doing? This is not cinema! We do not understand you!’ Then I understood that I had learned the wrong language of cinema, I had learned the underground language of cinema and not the Hollywood language.⁴

- ↑ Jonas Mekas’ installation The Beast, Lucca, Italy 2008, photo © Pip Chodorov

- Film still of a haiku in Sleepless Nights Stories by Jonas Mekas, 2011 © Jonas Mekas Studio, courtesy of Re:Voir

Jonas played with the form of language in his poetry, inventing words in Lithuanian or using words from his local dialect. His brother Adolfas who translated his poems, described the difficulty of making up words in English to match the strange Lithuanian words that Jonas had concocted.⁵ Jonas admired poets who push their language, condensing ideas into few words, ‘taking out from the language something that we didn’t notice or are not aware of. They use their language – the best part of it – they bring it to attention. (…). Take Dante: he is the one who helped Italians discover their own language. Instead of writing in Latin or some official language, he went to private people and spoke to the real Italians, whose language is really rich and he used that to write The Divine Comedy. So he helped them discover – he did not invent – but he helped them see their own language. (…) he used the spoken Italian language like nobody else before.’⁶ He admitted that he does the same in his own poetry: ‘I use much of the dialogue from my local area. And some of the new generation, for them it’s difficult. They need explanations and translations because of the local, rural dialect.’⁷

In the same way, Jonas also invented a new vocabulary for cinema. It is said that Jonas invented the diary style of filmmaking. In fact, the single-frame technique was already common in the 1920s avant-garde. The home movie had also become common since Kodak introduced the 16mm amateur format in 1923. Jonas also credits Robert Breer and Marie Menken, experimental filmmakers who were filming fast jerky footage throughout the late 1950s. Menken in particular was filming Notebook (1960) which also featured freestyle observations of nature and the city. Seeing her films encouraged Jonas to pursue his own particular style. But where did this style originate for a lonely refugee who had never made films? Jonas attributed it to his practice of writing a diary, which he also associates with poetry. ‘My films are diaries or keeping a diary. Each diary, each day, each entry – is like a film in itself. And some of them – a diary can also be very, very condensed, almost like a poem in itself. So that if you go to my film Walden [1969], maybe over 200 poems stranded together.’⁸ Jonas described a diary as ‘spotty. You can only capture bits of the day, glimpses.’⁹

Jonas’ films resemble Jonas’ poetry in three ways: through the imagery and rhythm of perception and memory, through the playful use of language itself, and in the freedom offered by these two forms. Jonas strings together impressions of the textures, the light, the weather, colours, the details sometimes blurry and unrecognisable, like the words he invented that conjure some essential reality; the perception of the subject rather than the subject itself. Just as a poet plays with the rules of language, Jonas played with the Bolex camera: this camera is very easy to rewind for superimpositions, very easy to take single frames, easy to change speeds mechanically, since its clockwork mechanism was manufactured in the Swiss factory of Paillard that made watches and music boxes. Jonas’ films are like a catalogue of all the visual effects one can make with the Bolex camera.

- Film still of Allen Ginsberg & Norman Mailer in In Between by Jonas Mekas, 1978 © Jonas Mekas Studio, courtesy of Re:Voir

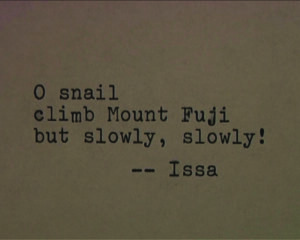

One poetic form that recurs directly throughout Jonas’ films is the haiku. In the film Lost Lost Lost there are two sequences: the ‘Rabbit Shit Haikus’ and the ‘Fool’s Haikus’, filmed in the early 1960s. These sequences do not technically follow the form of a haiku. They are more freestyle, although, during the first set, Jonas’ voice repeats a word three times, recalling the three-line structure of a haiku. In 1995, the Lithuanian American filmmaker Julius Ziz put together a selection of films by a dozen filmmakers called ‘three image films’ following a haiku structure. Jonas went further and made a ten-minute film called Imperfect Three-Image Films (1995). This was a series of haiku films in which three minimal shots create a mood, refer to a season and an essential moment. They are ‘imperfect’ because it is hard to tell, given Jonas’ shooting style, where one shot ends and the next begins. Some shots are a series of brief spurts of single frames. The haiku returns in Jonas’ later videos, Sleepless Nights Stories (2011) and Out-Takes from the Life of a Happy Man (2012). Shown as title cards on the screen, Jonas intercuts his scenes with Japanese haikus from the master poets. In this way, he weaves poetry into the fabric of his film and his life.

- Film stills from Imperfect 3-image films by Jonas Mekas, 1995 © Jonas Mekas Studio, courtesy of Re:Voir

If the expression in Jonas’ early poems is about nostalgia and homesickness, his film poems starting in New York in the 60s are odes to freedom. After a regimented life on the farm, then life in the factories, and finally the displaced persons camps in Germany run by the military, he was finally in the free world where he could reinvent himself and take chances, free to invent his own language of cinema. At the beginning of the film Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1972) he pinpoints this feeling of freedom to a moment in 1957 or 58 during a walk in the woods. It is telling that he recounts this feeling and shows these images as a prologue to the film documenting his first trip back home in 1971, the first time he could see his family in 27 years. The freedom of the United States and the nostalgia of home and lost childhood are inextricably linked, giving Jonas’ films a melancholy undertone to their irrepressible celebration of life.

Pip Chodorov has been a filmmaker and songwriter since childhood. As an artist, historian, distributor and film activist, he divides his time between his native New York, his adopted home Paris, and Seoul, where he teaches film theory and filmmaking at Dongguk University. He has made two dozen experimental films and a dozen documentary portraits of filmmakers including the feature Free Radicals: A History of Experimental Film (2011). Chodorov studied cognitive science at the University of Rochester and film semiotics at the Sorbonne in Paris. He has worked in film distribution since 1988 – for Orion Classics, New York; UGC and Light Cone, Paris; and the American Pavilion at the Cannes film festival. He founded the experimental film distribution label Re:Voir and the first gallery in the world dedicated to experimental cinema – The Film Gallery – in Paris where he also co-founded the cooperative do-it-yourself film lab L’Abominable in 1996 and the mailing list FrameWorks.

- ‘Jonas Mekas in an interview with Kiva Liu, One Way Bookstore, Shanghai, 2017.

- Jonas and his brother Adolfas fled from Lithuania in 1944 during the Second World War and emigrated to the United States in 1949. They were not able to visit their home country again until 1971.

- Jonas Mekas, Idylls of Semeniskiai, translated by Adolfas Mekas, New York: Hallelujah Editions, 2007.

- Jonas Mekas Q&A after a screening at Côté Court, Pantin, France, April 2002.

- Preface to Idylls of Semeniskiai, op cit 3.

- Op cit 1.

- Op cit 1.

- Op cit 1.

- Jonas Mekas interviewed by Pip Chodorov for Court-circuit le magazine, La Sept Arte, France, 2002.