Julijonas Urbonas and Gailė Griciūtė Talk About Their Collaboration on Extraterrestrial Sound

Julijonas Urbonas:

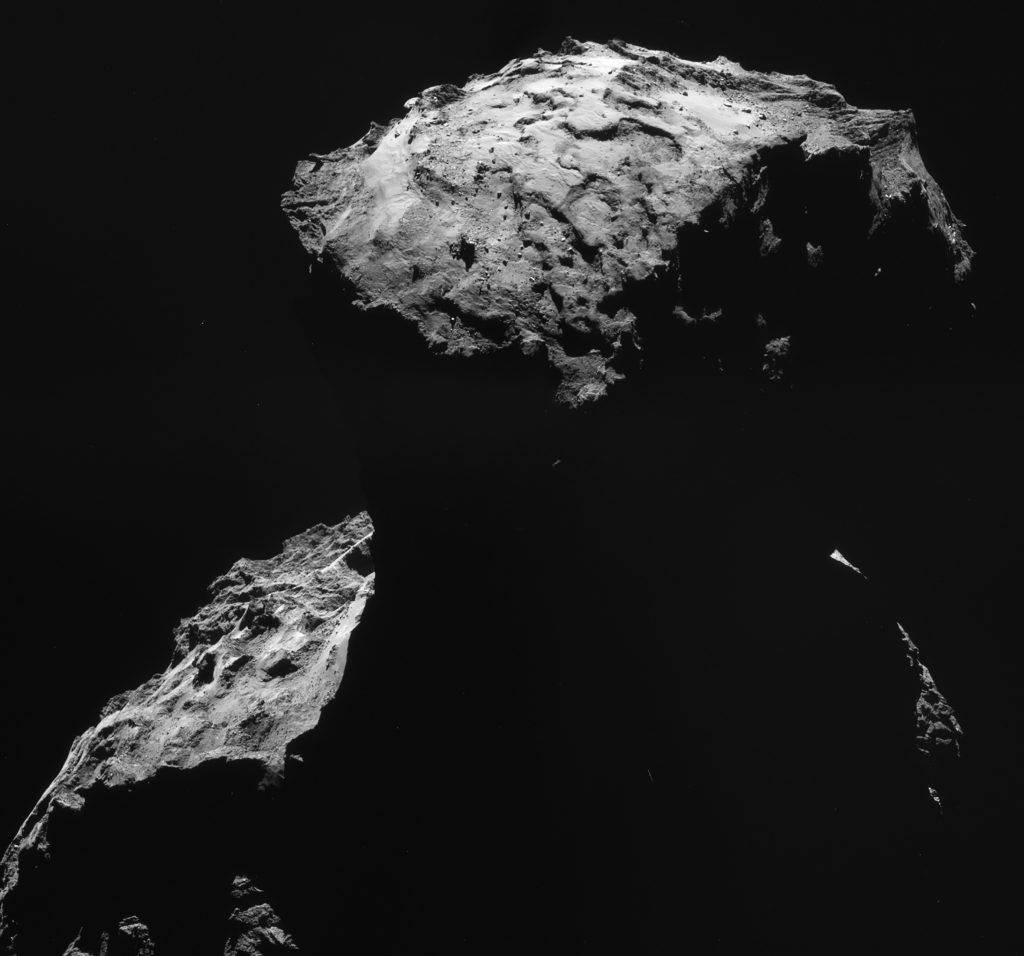

In 2018, I was commissioned by Operomanija, a Lithuanian production house for new musical theatre, to direct and design the set for the opera Honey, Moon!. Collaborating with composer Gailė Griciūtė, librettist Gabrielė Labanauskaitė-Diena and others, I turned the opera into something between a participative performance and a live sculptural installation. Scattered across the 1000 sq. m exhibition hall of the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius were seven revolving platforms on which twelve performers – vocalists and instrumentalists – were strapped and performing. Covered with custom designed fabrics by illustrator Célestin Krier, the platforms looked like extraterrestrial landscapes, yet on closer inspection those semi-transparent textiles revealed various conglomerates of narrators, singers, a flautist, a clarinettist, a violinist, a cellist, a pianist, and a synthesiser player. The public was invited to walk around the constellation of sets and explore the play between micro, macro, and cosmic scales, encouraging the confusion between what could be considered as human and planet. For me, it was a true space opera dedicated to honey, the Moon, honeymoons… Honey, Moon!

Could you please say something about the creative process of composing the music for the opera ‘Honey, Moon!’? What was driving your sonic imagination? How did you approach the cosmic aspect of it? What were the challenges besides the mobilised listenership and the vertigo experienced by the performers?

Gailė Griciūtė:

As I was writing the music I was thinking about there being two layers to the story: the personal intimate journey versus the cosmic journey on a bigger scale. I used different sound sources: field recordings, modular synthesisers, a chamber music ensemble and speech and was navigating between very delicate sonic gestures and an overall immersive and meditative sonic experience, where small, subtle movements merged into a constantly moving steady state.

It was a challenge for performers to play while being in motion and to hear themselves together with the amplification of sounds, which travelled in space; it required very attentive listening and physical mobilisation. In general, all of the participants served the purpose of creating some kind of bigger organism – the sense of being an individual had to be let go of. The musicians were covered with painted fabric and the gestures of movement created by playing their instruments formed a collection of curiously moving sculptures.

JU:

When I talk about the conditions of space and the ‘cosmic’ in my artistic practice, I usually refer to altered states of gravity, such as weightlessness, artificial gravity, hypergravity, etc. Looking from that perspective, the piano that I developed for the opera could be seen as a hypergravitational simulator for the sound of a piano. Later, I advanced this idea so that the piano could work as a separate and independent installation, and the first occasion in which it was tested was the solo show ‘Planet of People’ at Galerija Vartai. It was staged as a three-month performance-experiment or high-g sound training with weekly concerts of yours in which we were increasing the speed of the platform and contemplating the effects of altered gravity on both the piano player and the composer, the instrument and the sound, the music and the listenership. Capable of producing 3g (three times greater than that of Earth’s gravity), the centrifuge became a hypergravitational sound-stage. In addition to this, the centrifugal force of spinning produced unique gravitational fields that varied at different points in relation to both the player and the piano. The force increased when further away from the spinning axis. Thus, the fingers on the keyboard, for example, felt a weaker pull than the head or the back. Furthermore, the movement of the playing hands were affected by the complex Coriolis forces as were the piano strings. The constantly changing orientation of the instrument affected the way the sound was transmitted. I like to think that all of these unique physical and mental conditions gave birth to what can be called an extraterrestrial sound.

What was it like to ride, play and compose the Hypergravitational piano?

GG:

For that composition I used fragments from the opera Honey, Moon!, excerpts from prepared piano parts. My experience with the moving platform was very subtle, it did not change the way I played in a visually effective or dramatic way. But I didn’t feel as stable in the way my fingers made contact with the keys, and the way I controlled my body weight, which resulted in a certain tension in my hands and that, of course, affected the sound. The composition that I wrote for the moving prepared piano had certain patterns and quite an open form; I had the freedom to experiment and choose the material. The physical conditions made an impact on my choices of course, but they also conditioned the precision of execution.

JU:

I consider the Hypergravitational piano piece as a soundtrack for both the exhibition and the project Planet of People in general. There is something eerie in the music as if the piano was possessed by a spirit. Or maybe I am too biased by the hauntological music I was listening to a lot during the development of the project?

GG:

I guess we inspired each other during the process. It started with the opera Honey, Moon! as the compositional material was taken from there. Hypergravitational piano is a composition for prepared piano, which I use in my practice a lot, as a tool to get in between the well tempered notes on the piano – it also serves as a component of the unpredictability, which I find important in the compositional process. So in this particular piece I was playing with the idea of using the instrument to get somewhere else. Repetitive passages also have a tendency to create a type of non-linear narrative, a sense of a sonic landscape and an immersive, atmospheric experience. I was also interested to feel how the use of preparation with magnets on iron strings, hit by a felt hammer, controlled by wooden keys and the flesh of fingers would complement 3D images of scanned bodies.

JU:

What effect have such projects had on your later sound art/musical practice if any?

GG:

I am a performer and a composer and so, for me, it is interesting to think about the performer’s role, musicianship and individuality in the context of a large composition involving many individuals. I search for ways to leave freedom for the performers to make choices and to sharpen the process of contemplative listening and creating one attentive experience of a sonic whole. My recent work, A Body Of Water, commissioned by the Lithuanian Composers Union and Gaida Festival to be premiered by the Lithuanian National Symphony Orchestra involves different aspects of freedom for the performers to make individual choices, while also remaining part of a directed sound mass.

JU:

Actually, I quite often find myself being not just inspired by certain music, but guided, even manipulated to such a degree that I could consider some of my projects as a scenography or a stage for those musical compositions. Thus, my practice is like making a movie by starting with the soundtrack.

If you were commissioned to produce a score for a sci-fi space film before the script was even conceived, how would you begin composing?

GG:

I am inspired by so many different things and very often I like to think about sound composition as sculpture, considering form in time, and shapes and different textures, merging and transforming.

I am inspired by environmental sounds, certain states of mind, and melodies inherent in human speech. But in this case, I think I would try to clear my mind of thoughts and take the ideas that emerge from there as a starting point. Another very important element in my practice is failure: I embrace it and use it to guide me out-of-bounds.

- Julijonas Urbonas, Honey, Moon!, as part of the New Opera Action festival, Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius, 2018. Photo: Aistė Valiūtė & Daumantas Plechavičius

Gailė Griciūtė is a Lithuanian composer and sound artist. She graduated from the Sibelius Academy of Music in Helsinki, Finland and Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theater, and was also a guest student at the Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. Gailė is a member of the performance collective Eye Gymnastics. The group’s works have been shown at various festivals in Lithuania and Germany. Some of the festivals and concert series where Gailė Griciūtė’s sound and art projects were presented include Ahead, Jauna muzika, Soundscape, NOA, Estonia (Vilnius), Counterflows (Glasgow), Sound Art Festival (Kaliningrad), Unsound (Krakow), Labor Sonor (Berlin), Tectonics (Tel Aviv), Atmospherics (Haus Der Kunst, Munich).