On Tracey Emin: ‘Everything Has Come Through Me’

Sex sells, and poetry can get you sex if you know how to write. But poems rarely sell. Tracey Emin does, but she did not intend to by making poetry: in fact, she wanted to exploit her exploiters.

Visual artist Tracey Emin lives in a dimension swarming with words that reach the higher institutions misspelt, and spill a raw, necessarily disarming truth. These words are the very ones the artist takes as a panacea, to hold on to her strongest emotions. Born in England in the 1960s, Tracey Emin made her name as a member of the Young British Artists group. Through various mediums she unveils parts of her life, drawn more or less explicitly from her memory. The great intimacy of her work lies not only in the themes she explores – femininity, sexuality, motherhood and childhood, rape and abortion, silence and betrayal – but also in the extreme intensity of her life experience. Tracey Emin never shies away from the impact of her emotions, thus demonstrating a certain commitment to truth. All too often approached through a psychologising prism, her work has been the subject of ambivalent critical reception, sometimes judged to be hysterical, sometimes narcissistic.

Tracey Emin first made her name in 1999, when she was nominated for the Turner Prize and exhibited her installation My Bed (1998). The work is literally extracted from reality: it is a recreation of the artist’s bedroom. It features a bed with dirty, unmade sheets, strewn with tissues, cigarette butts and condoms that have fallen onto the adjacent rug, an equally busy nightstand, and bottles of alcohol at her bedside. Tracey Emin explains that this installation was the result of several destructive days spent in this bed. By realising that what was her own condition could become her art, she found healing, and created a system that knew no separation between herself and her work. French author Georges Bataille writes in L’Expérience intérieure that only ‘the desire for poetry renders our Misery intolerable’. Desire, and poetry as a turning point. It is this same outward thrust that guides Tracey Emin throughout her career, in the construction of an oeuvre that oscillates between a conceptual niche and mass culture.

Just like writing, Emin finds sex to be primal; indeed there’s something primitive about every image she creates, like she could have drawn them a thousand years ago. Her creative gesture, so fluid, reflects perfectly the emotion that generated it. This close connection with her sexual self comes from her very physical youth, which she recalls saying that all her life she ‘worked constantly hard not to be that animal.’ Now at the antithesis and working consciously every day as an artist, Tracey Emin navigates through her feelings. The quest for herself that she pursues by reinvoking subjects and giving them new words, colours and shapes, over and over again, has made her a great poet.

Poetry is not something we tell ourselves, nor a story we tell others. Sex, like poetry, is the substratum of an instinct, that of belonging to the world as a thinking, feeling, desiring being. To be a poem is to hide wonders, to radiate your vitality to the reader. We see John Giorno’s selflessness when he dedicates his poetry to his lovers and all the tenderness he devotes to them. For Tracey Emin, dedicating herself to her art, to her poetry, also means being faithful. Faithful to her instincts, to her desires, and to those who light her fires.

The autobiographical dimension of her work seems to bear further witness to the value she places on lived experience. It is impossible for her to write anything other than what she knows. Indeed, Tracey Emin’s sex diary is retraced from her earlier works, such as the film Why I Never Became a Dancer (1995). Growing up in the small seaside town of Margate, sex was the only thing to do. The artist recalls her lovers, mostly older men who would take first advantage of her and her frivolity. This work is a kind of initiation tale, a journey through love, pain and loneliness.

Margate 1978 – The Summer was so amazing – nothing to do but

dream – It was ideal – and there was sex. It was something you

could just do – and it was free. Sex was something simple – you’d

go to a pub – get walked home – have fish+chips. Then sex.

Tracey Emin

Why I Never Became

a Dancer, 1995

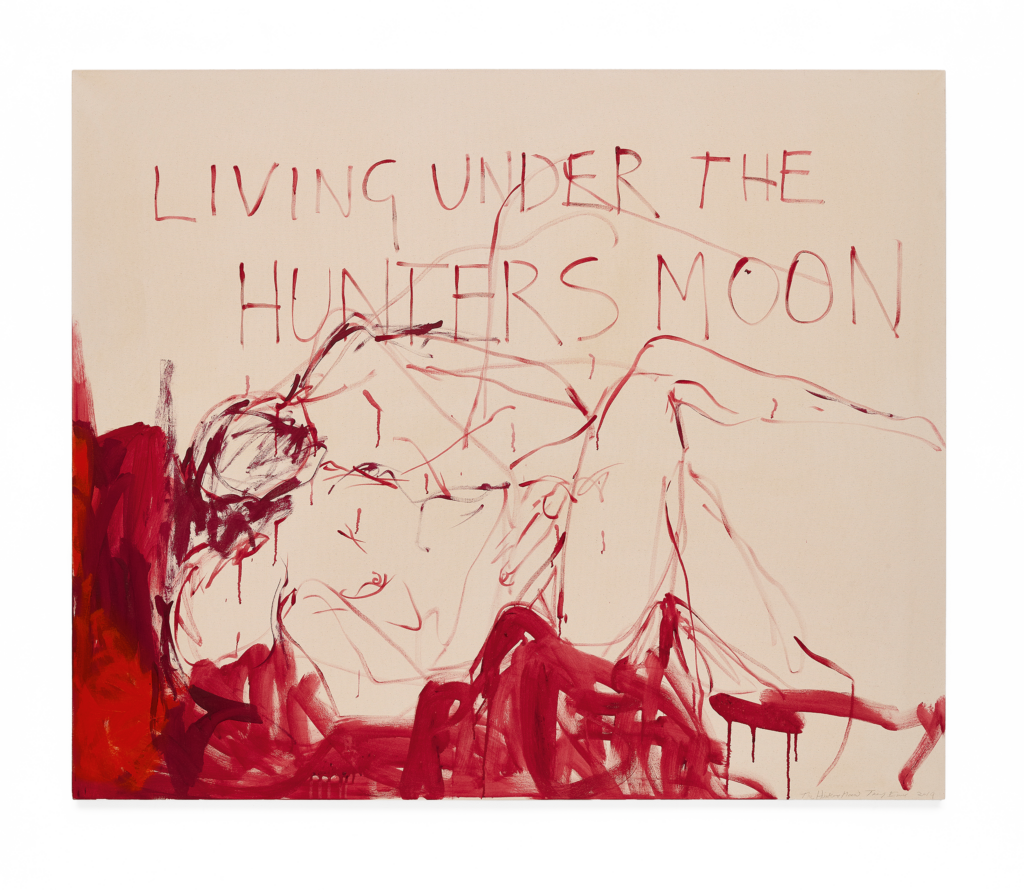

Tracey Emin’s poetry is also striking for its corporality. The artist compromises herself and her integrity, leading the viewer to a sensitive deflagration. Emin’s poetry is even the backbone of her visual productions. Each of its vertebrae contains a founding narrative, which, articulated one to the other, outlines the issues at stake in a deeply moving body of work. A spinal column is something intimate: the artist surrounds it with muscles, training her words, and creating art from the depths of herself, so well interwoven that her life cannot be dissociated from it. But one can also feel this physicality in the way she creates her art: her paintings are palimpsests of multiple bodies, layers and layers of paint before finding the one scene she wants to offer. In the way she has kept so many memories stacked in her mind, multiple images overlay one another until the right one rises to the surface. Sex in her work is a burst, something so crude that it breaks canvases.

Emin is not as spontaneous as she first seems. She explains that her working process comes from writing first and thinking about her art before making it. The titles of her exhibitions and drawings are poetry, striking monostiches like apparitions. Her use of language reminds us of the namesake with what is also a tongue. The living organ as a tool, allowing the artist to say out loud her poem, to pass it on to the others, as well as the tool that makes kissing them possible.

Sex like poetry is a matter of forms and shapes, of senses: touch – smell – hearing – sight (another thing about her work is that she often writes backwards, engaging the viewer’s body in a poetic gesture, holding the drawing in front of the window to reveal the writing), of rhythm: sound poetry, bruitist poetry (Emin’s 1997 drawing entitled La la la la la depicts cunnilingus), even haikus, prose or verse. A matter of body: its fluids, its blood, its saliva, as the expression of guttural feelings. Just like literature, sex reaches your heart, enters your mind, soils your inner self. A poem can spit on your morals, caress your thoughts or torment your sleep. Poetry is an opening: it widens the mind, stretches the soul.

Sexo é ima

Sexo é imaginação, fantasia

Amor é prosa

Sexo é poesia

Sex is imagination, fantasy

Love is prose

Sex is poetry

Brazilian Rockstar

Rita Lee

Then, spirituality happens to be utterly sexual in Emin’s paradigm. In her visual as in her textual works, the experience of sexuality is close to a religious feeling. Although not religious herself, she depicts Eucharistic scenes, the descent from the cross, angels or the Last Supper, intertwined in pornographic sketches in her book One Thousand Drawings (2009). Emin also uses more ambiguous but historical motifs such as phallophanies, in a scene where a woman is mourning Christ in bed. This Lacanian symbol echoes her sacrificial feeling in romantic or erotic relationships.

Considering now: sex as a poem as a prayer. Lamentations are part of her works, especially in the year 1997 as in And there was nothing but white light, where she writes ‘You had a gun in your hand and you held it at my head – I was like a ghost and my mouth was open – Come unto me’ the latter expression being a call for Jesus from St. Matthew’s Gospel. And she creates many more ambivalent verses, such as Oh God (‘Oh God you made me feel so beautiful – And then I wanted to feel it again and again – Come in my face’) or her most famous and recurring proclamation I Need Art Like I Need God.

Through these examples and other works, her art is tainted with submission and devotion as part of sexuality. Sometimes an incomplete image, a snippet of memory, takes shape. The female faceless bodies she draws are often lying motionless, legs wide open, or standing helpless and naked: the sacrificial imagery of the martyr is omnipresent, and violence is sometimes very explicit. In Chess Set (2008), Tracey writes ‘I always wanted you to make love to me, even when I begged you to stop.’ The writings of Saint Theresa of Avila, just like St John of the Cross’ Spiritual Canticle, have this same poetic trance. In The Life of Saint Teresa of Avila by Herself (1565), the saint expresses the violent ecstasy of penetration. This text about transverberation is a great poetic parable that can be very much related to Emin’s work: sharp pain and moans, glare, guilt and forgiveness. In My Life in a Column, the artist ironises on being called ‘such a size queen’. Eager for a more intense, fervent experience of life, we find that her poetry and way of being in the world are, once again, inextricable. Such roughness is rarely asserted when it comes to desires, while it translates the complexity of the mind. One must go deeper.

Sometimes sexual behaviours are paths to something else. People get bored of everyday life and have sex with strangers on Christmas Eve, in a parking lot in the pouring rain, or exhausting fornication with someone they won’t ever build anything with. These reckless times allow them to feel their deepest nature in all brutality, or to take a step aside from themselves. The naive self can rather enjoy these seminal poems of humanity in its naked truth. For young people especially, the transcendence of one’s sexual being is perceived as empirical; as formative when they’re not freeing experiences. As a young girl, such experiences are pure transgression. There is beauty in witnessing what shouldn’t be. In reaching the intangible, remelting steel and sowing disorder.

Sex for me had been an adventure – of

learning and innocence – some wild escape

from all the shit that surrounded me.

Tracey Emin

Why I Never Became

a Dancer, 1995

Considering the sexual dimension of Tracey Emin’s work as well as its autobiographical essence, her poetic expression seems to come from a vital energy. Emin’s career has seen her growing and changing, with a turn from sexuality towards her art. In a recent interview she said that sex is no longer what drives her, but faith, God, love and spirituality. The aim is now to inject her sexual drive into her art in a kind of Faustian pact. She lets her mind go into further places, navigating her past and present life, because Emin keeps evoking her younger self. She still needs to express her trajectory, saying that she could be any woman. Being more mature now, she emphasises that the tremendous physicality of her earlier works is still relevant, although ‘this screaming adolescent girl hasn’t got any more energy left’.

I write to run through myself. Paint, compose, and write: run through myself. That is the

adventure of being alive.

Henri Michaux,

Passages, 1950

Tracey Emin has never disapproved of her incandescence. She knows her desire is what carried her forward. By refusing falsification, the artist dived into her inner wonderland where feelings explode, sometimes as painfully as they must be. Her truth has always been to not have secrets, allowing others to relate to her profound experience: it has never been about her. Being a poet has been the way to an honest, greater life.

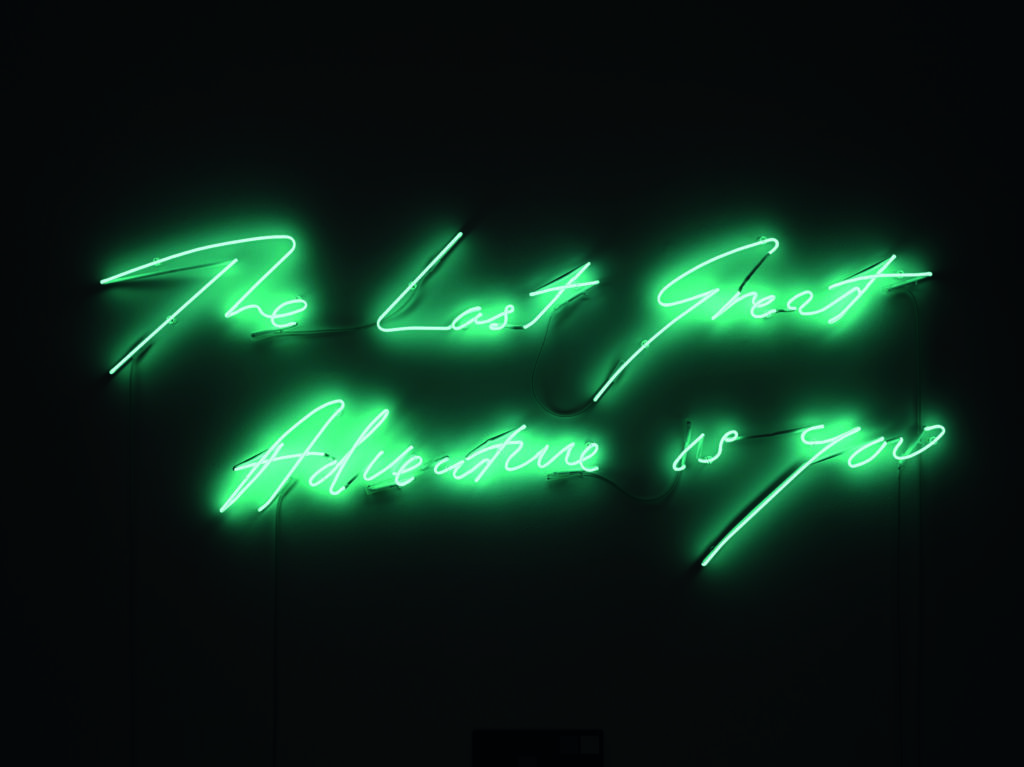

And the greatest minds have been writing about adventure, knowing that it could never be just an outward thrust. They teach us to look inwards, to be desirous of knowledge, others, everything. Relentlessly, Emin chooses her selfless truth over morals, beliefs or politics. From her exhibition titles ‘Exploration of the Soul’ to ‘The Last Great Adventure is You’, she refuses an evasive approach to art. Exploring has something to do with time, patience and depth. To be an adventurer is to live according to one’s pace, believe in wonder and know that the answer probably lies elsewhere. The aim could be to discover. Sex, like art, like poetry could be unveilings, rather than display or demonstration. Emin’s radicality does not consent to poetry as escapism. But sex as a poem – as a hunt for truth.

Louise Brunner is curating cultural and editorial projects. For the Centre Pompidou, she is a programmer for Extra!, the festival of living literature, whose 8th edition will be held in Paris in September 2024. As a scholar, she is currently preparing a research project at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales, focusing on Tracey Emin’s prolific textual work.