The Loop

Saulius Čemolonskas – Sal – was a DJ, vinyl collector, experimental musician, and a sound designer. An escapee from the USSR, Lithuanian by origin, stateless for a while. He lived most of his life in London. To most of those encountered, he has been a great source of musical knowledge, a creative counterpart, and a bit of a pain in the ass.

I met Sal in London, around the year 2011. He arrived on an old bike, wore a purple zip-top and a grey cap. He didn’t have a mobile phone. He told me to rely on ‘trust’ for our meeting. I did. We went up to his studio in Bethnal Green. We had tea and chatted. He told me he was allergic to technology. It was hard to make sense of his stories the first time around.

His story here is told mainly through memoric fragments. Of his own, of his friends. I met them while making a movie on Sal. Yet memories don’t always represent reality, nor the truth. Intertwined with emotions, they become biased. Biased is this portrait of a person who is now gone. Sal’s ashes rest in his friend’s studio in London. For the time being. Jingles, bits of sound, noise and fragments. All subjective. That is how Sal would tell a story. In feedback loops, in snippets. Make of it what you will.

Friendly Definitions

Sal was a dear friend, Laure Prouvost says as we are drinking coffee in Notting Hill. It is 2019, and it’s winter. Sal has been gone for more than a year now. We chat, but it is extremely noisy in this cafe. I hope the recording will be ok. She compares him to a tricky horse. She says she went horse riding when she was little. And would always pick the horse that was a bit feisty, a bit difficult. He was like that, she says. Extreme intensity, dearly passionate, extremely talented in what he was doing with sound and experimentation. She continues. Life is a bit unfair to these kinds of characters. She looks down at her cappuccino. Just less of a norm, she explains, just off norm. And that was what attracted me to him as well, she says. He was like a child. You had to work around him and with him. At the same time he was so loving, so loyal, and passionate, he says. It would be very hard to live with him, but as a friend he was perfect. He would be extremely there and then go. Sal would arrive and leave. He was like that.

A few months back, and Martin Stiksel and I are in east London. We pull out some chairs from the garage so we can sit outside. It is a sunny morning. This garage belongs to Sal’s friend Felix. Sal had stored his stuff here. Some furniture. Some vinyl. Some record players. I had never met Martin before. But I had heard a lot about him. I also stayed at his house once, when Sal was house sitting for him, and organised a party there. The day is good and there is an aeroplane passing above our heads. We stay quiet for a bit, waiting for the plane to pass. Sal was Martin’s friend and a collaborator. It seems like Sal had a certain life cycle with people, Martin says. You get going, everything is fine… and I would defend him: look he is a polarizing character, he pisses people off, but I don’t care, because the result of the work is so great, that it doesn’t bother me too much. Martin continues. He had a knack for pissing people off. And he liked doing that. And at times it was funny, but sometimes – not helpful. Behind us is Sal’s garage. The garage that served Sal as a storage space. And an occasional place to sleep. But that was towards the end of his life.

Terry Burrows is a writer and an experimental musician. I met him in his flat in Hackney. He doesn’t leave the house very often. He used to play music with Sal. And chat. And listen to records. And talk about life. And drink coffee, he says. I always had a feeling that Sal had a very strong moral code of his own. I nod. Everybody else’s standards just didn’t apply to him. I listen. He was a very free spirited guy, who was difficult to control. Difficult for himself to control. He pauses.

Gerard Abeille is a sound designer and recordist. We chat in a cafe, in Swiss Cottage – an area in north west London. He was my best friend, he says. You know, he was not a breeder. Even though he had a daughter in the end, he was still not a breeder.

The following memory belongs to Artur Builov. He was an actor. Now, a yoga teacher. We drink tea in his flat in Vilnius. He remembers: I would walk down the street with Sal. He would stop, look at me, and say: look man, I think I will continue on my own from here.

The Records

Sal was born in Kulautuva, a small town in Lithuania. As a teenager he started collecting and exchanging records. Lithuania was part of the USSR. He worked on construction sites in his hometown. All day, all summer – he says – to earn money. Still at school. Sal and I speak in his kitchen. It’s 2012, and it’s summer. I want to know what it was like for him in Lithuania back then. The reward was buying records, he explains. The exchange. Everyone was bringing me unwanted music. He smiles. He is proud. The music that was not popular, he continues. Back then everyone wanted disco. After that, disco rock. Then classical rock and metal. Soul and black music was not very popular, he says. He collected the ‘non popular’. Soul, funk, jazz. An exchange market. It became his lifestyle.

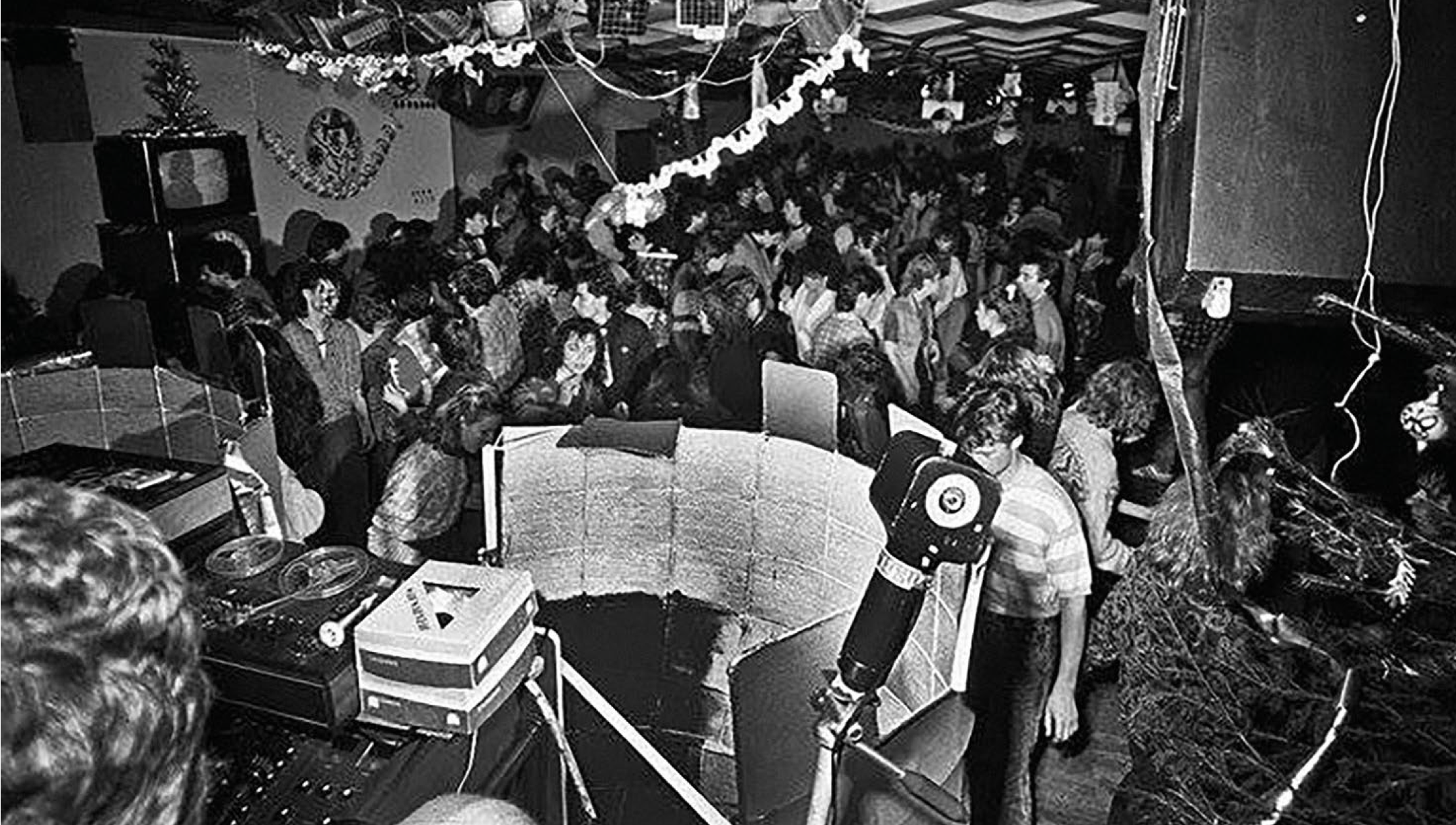

Sal became a DJ in Kaunas, in the 80s. He played in a club called Trestas. They often played Western music there. They organised the first metal discos. Spirits were high. And so was the push back. Everyone was constantly monitored by the KGB. Unconventional hairstyles and dress codes drew attention. One vinyl cost a month’s salary. Sal often carried 10 or 20 of them. To give out information about the seller meant putting friends and family at risk. Parents were confused. Are the kids doing something good? Are the kids doing something bad? This whole Western music business. They made up record prices during interrogations. You had to avoid telling them the unnecessary stuff, Sal explains. Employ some fantasy, he continues. And stick to your story.

‘Iron Maiden. Russian Army Go Home. Metallica.’ Sal and his friend wrote on a tank once. It is publicly exhibited in one of the forts in Lithuania. They did it at night. Before a military commemoration. In the morning people arrived with flowers. The feeling was unreal, Sal says. It was as if we’d done something quite remarkable.

Clothing and vinyl often came from relatives living abroad: the US, the UK. Music in the Soviet Union did not sound like that, Sal says. Everything was different in the West. The quality of sounds, the machines. He imagined. American Voice. Radio Luxembourg. The West was imprinted in the vinyl inlays. The smell of pine. Information about the artist. This flared up curiosity. He wanted to go where nobody from the USSR had been. He wanted to be where the vinyl was published. He is talking about New York, he is talking about London. Sal just wanted to escape. To speak freely. But to say what? He pauses. It is 2012, and it has been more than a few decades since he was in London.

The Escape

Sal had a younger sister and brother. He and his brother didn’t get along. The brothers loved their sister dearly however. She was still at school when it happened. She hung out with them at times. They all belonged to different groups. All alternative. All rebellious. They did, however, have some friends in common. But mutual friends didn’t always realise their family ties. And then the sister had a headache. It happened suddenly. She died. She was possibly misdiagnosed, some say. Possibly mistreated, say others. Everyone was lost. And then there was silence. No one spoke about it again. Sal started playing different music at the discos. They just didn’t have the same vibe anymore. He left the country shortly after, Terry says: it seemed as if there was almost a before and after sort of thing… and I didn’t even know… that she existed.

I want to go to the United States, Sal said. Gerard is now telling the story. The authorities told him: you need to wait for three weeks or a month. Sal was like: I am not waiting, I want to go now. If you want to go now, we will send you to Israel, they said. And then again, Gerard: so this is Sal, in Israel. 1989 to 1991. They gave him a TV set, 2000 dollars, and he worked in a kibbutz. And he did it for a while. And then he was like: this is rubbish. He took his money and came to London.

Artur continues. He fancied this girl from his hometown, you know. But she was a bit above his league. They did like hanging out together though. He went to Israel. And then she sent him a postcard saying she was in London. So with that card Sal went to some kind of migration office… and managed to get permission to leave Israel.

And so, Sal arrived in London. Without much information about the place, Sal explains. Only a little bit… from a book of Sherlock Holmes The Hound of the Baskervilles. He got off the train at London Bridge. He says he imagined it slightly differently. London was like a book. Like something you find in the library. Like a linocut. The shadows, and the buildings. The basement flats. The surreal architecture. Contrasts, walls, fences, the bridges. He explains: it seemed photographically quite cosy when I first entered. It was just a picture, he adds. This was how I wanted my background to look.

Limbo

For a long time Sal was in a limbo state, in terms of his citizenship, Martin explains. He left Lithuania while it was still part of the Soviet Union. Lithuanians did not really feel responsible. The only official documentation he had was a Soviet passport. The Soviet Union didn’t exist anymore. He couldn’t really travel. Eventually he did get a Lithuanian passport, but it involved a process that took many many years. Martin adds: but he made great hay out of the fact that he was stateless. I think he kind of enjoyed that. Whenever someone would ask him where he was from he would say: I am stateless.

The Encounters

Artur and his friend arrived in London in 1991. They decided to look for a job. They were told to say ‘cash in hand’. They went around. The days went by. No job. Artur remembered someone telling him: there is the Lithuanian House. And there is a guy living there, somewhere, in the basement. Artur tells the story: we arrive. We go downstairs. There is some kind of wooden door.. We knock. We hear a sleepy voice. I mean, it was midday. He giggles. Sal just woke up. His room… how to put it, was a creative mess. Artur describes: Sal had long hair at that time. To me, you know, long hair meant ‘a hippie’. All those who had long hair in the USSR were hippies. Next to Sal, on a mattress, there was also a girl. Both seemed hungover. Artur remembers. Sade was playing. He says. Probably even Smooth Operator. He laughs again: I mean, some sort of absolute nonsense. Sal asked us for a phone number. I thought nothing would happen. But two days later he called. At 11pm. One of you has to be at work shortly, the voice said. At three o’clock in the morning.

Gerard met Sal at the Market Bar, at work. He recalls: in 1989 Notting Hill went through a transformation. Many people moved in. Trendy, middle-class-arty people. Market Bar, at that time, catered for them. Gerard continues. The environment was Gothic. They played Northern Soul . The place was open after 11pm. I worked there behind the bar, he says. Sal was working there too. As a kitchen porter. And the first conversation we had was about Can. Gerard had just bought their latest album. It must have been 1993. We became friends straight away, really, Gerard says. And nostalgically: two lost souls in London. Sal’s home became his refuge for a while. For the first four or five years, Gerard says. I had never had friends from the Eastern Bloc before. He is French, he explains. He continues: Sal had a Yamaha effects unit at that time. My favourite one was called ‘infinite’. It created loops. We used to make noise. White noise. Then we would mix in some ‘poppy’ track, or some Drum & Bass. And five hours later we would have a recording of six tapes.

Martin met Sal on a Digital Sound Design and Music Production course. Sal told him later that he actually wanted to do a film course. But he didn’t get in. From here Martin tells the story. So there was Sal, sitting in the lobby of a college. He saw an ad for a sound course and thought: oh well, I will do that then. It was the very early days of digital music production. We had very basic Macintosh computers with Cubase, Martin explains. It must have been 1999 or 1998, last millennium for sure, because we celebrated 2000 together. Martin continues: at one stage I fancied myself as someone with great musical knowledge. I challenged Sal, I mean, I was in my 20s. I said: make me a tape where I don’t know anything, but I like it all. Sal said ok, alright then. And he made me a tape with songs that I had never heard. Nor the singers, nor the labels. But I liked it all. Martin thought: oh wow, this guy, obviously, knows his stuff. It was a very humbling experience to learn that there was a whole world of music that I had no idea about, he says.

Fast forward to the new millennium. Terry has a dog. He is in Hackney and it is late. It was last thing at night, Terry says. I took the dog out to pee before going to bed. And Sal was out there, having a cigarette. And he just… started talking ‘at’ me. He asked me: what do you do? I said: I’m a musician and write books as well. Sal said: I am a sound designer. And immediately, we started talking about music.

And Laure. When we met, I was struggling, completely, as a human, as well as an artist. I was quite lonely, I’d just finished college, she says. I wanted to experiment with narrative, and went back for a year to Goldsmiths. I asked Sal to do the sound for what was a performance. She recalls: and we were just perfect. Leaving space for each other. And then he would become annoyed, like: fuck this, I was carrying things for you all day. She continues: at the same time, when he was there, we enjoyed doing it so much. She means the performance. We would practice a lot in Bethnal Green, where he had a big studio.

The Work

And the first job Sal found for Artur and his friend was to make sandwiches. It was horrible, Artur remembers. You stand there, cutting bread, like a machine, he says. A friend left London shortly after. But Artur decided to stay. Here he was, back at Sal’s basement flat. Again, in need of a job. Sal was working as a kitchen porter at the time. He went to his managers to ask for an extra job. For his friend. The managers said no. He shouted, he accused them of their privilege. This guy is in a difficult situation, Sal said. He meant Artur. He continued until they gave up. Sal and Artur started doing dishes together, at the Market Bar. Sal also took his friend in, to live in his basement flat.

Gerard exhales. Then something happened in 1996. He said: I am done with being a kitchen porter. And that was the end of it. It was about pride, Gerard says. Everyone was equal for Sal, and had to be treated equally.

Then there was Martin and Sal in the autumn of 1997. They were doing a sound course together. At some point Martin’s flatmate, working for a design company, was in need of a sound piece for a commercial. This was the first time Sal and Martin worked together. Martin suffers from a fear of a blank canvas. Sal had the confidence to place things there, in a new arrangement. The project went well. The client was happy. They did another project together. And another. They started a company. New Breed of Alternative Workers, they called it. All the software was illegally downloaded, they didn’t pay for anything. Digital music peaked. It had become much more user friendly and mainstream. Martin’s grandfather got him his first laptop. I was with Sal in the park, Martin recalls. With the headphone splitter, so we could both hear the music, we were working with samples loaded in from CDs. We stayed in the park until the batteries ran out. Making little jingles. It was great fun, Martin smiles.

We kept getting more work, and bigger projects. In the end we were pitching for Mercedes, Vodafone’s sound logo, commercials with David Beckham. Stuff like that, Martin says. But then the internet took over and ate music as a whole. The whole custom made sound business world crumbled. Record labels were not making any money anymore, and were instead pushing into the market of pre-recorded music for commercials. There was no more money in jingles.

The Internet

Martin continued to study. He met some programmers. He said: why don’t we do something so you can listen to music online? They knew a lot of musicians at that time. But the problem was always the same: how to get your music heard without involving radios or labels? The first ADSL connections showed up. They started playing with Napster. They knocked up a simple website called Insign. A lot of people were uploading their music by this point. Martin says: our stuff was there. Our friends’ stuff was there, and then the whole thing exploded. People were uploading music from all over the world, he recalls. They created a tracking system based on what people listened to before. Sal helped by ripping and uploading CDs. He enjoyed doing that. Martin clarifies: but he was never part of that internet project. It was such a fluid thing, he says, we played a lot of computer games, smoked a lot of weed. Someone would bring a piece of music, someone would bring in a design. It was all great fun. And later those around would say: I started last.fm.

Last.fm was later sold to Sony. For millions.

Laure says: he told me how he had a contract there and then they shredded it, no? She continues: it was still a bit… It became more about money than friendship. It would have been nice if he had his own flat, she thinks. Sal didn’t have a mind for business that’s for sure. He was the content. He would search for music, he would upload so much for them. He was into the creative side of music, more than the mediation. It was just by chance, but he was there, I think, more than… She pauses. And it is not blaming anyone, for sure, there is no blame, but… I want to support friendship as well. She says.

And then Gerard speaks. Sal lived on nothing, he needed a few quid to buy records. Records were his currency. He would find a record for three quid and sell it for twenty. Occasionally he would also perform as an extra. In big film productions. Like, in a Spielberg film. When he was skinny he could be a refugee camp prisoner. At other times he would also look like a German soldier. He was perfect. That’s why they loved him, Gerard says. But he eventually got sacked. For taking pictures on set, for example, while playing dead. He laughs.

When we were together it was often to prepare a performance. Laure remembers. We also did a gig for the Whitechapel Gallery. She continues. It involved stories about my grandad who got lost in a tunnel, who was a conceptual artist, and who was digging a tunnel to North Africa. There were many stories made about it. For me, Sal was in a tunnel as well, he was digging. We were digging over realities, over sensations, over languages, over words. Especially with music. He made music for my videos also. Which… was nice. I would tell him that I need a watery, disturbing sound. And he would bring something and I would say… This is not what I imagined, Sal! She laughs. But at the same time it was perfect. Sal made a strong impression on people. He was not pushing himself in front. He was really sensitive in the band, she thinks. He was so happy as well when he was making music. When he was in the creation. It was his language, the rest was not. Also, English was not his first language, it was not mine either, so it was really through art that we could talk and get something much more complex, she says.

The Gigs

Sal constantly dragged Artur to concerts. Sal knew everything. Where Alice Cooper was playing, where B.B. King had a gig. He wore headphones everywhere he went. At home there was always a radio on.

A friend of a friend called Felice invited Sal and Artur to a concert by Brian Adams. She says: he was my classmate. Then we were in, and for Artur it was the first gig of that scale. Wembley Stadium was full. People were screaming. Sal and Artur left the lodge. They passed security guards. They entered a room. And then another one. Artur says: with things to eat. They started drinking. Another VIP room. They discovered: it’s Brian Adam’s birthday. They heard ‘Felice! Brian!’ behind them. They turned around. Brian is short, Artur says. Skin – so-so. Dirty t-shirt,e describes. And then Sal goes: do you have a job for us? To carry speakers or something? His request is quickly passed on to a secretary. Brian does not give them a job, but extends another invitation to a concert the following day. And Sal recalls. It was in early 1992. Brian gave me some fireworks. I didn’t use them. I didn’t like fireworks so much. I don’t like shooting.

Fast forward to the end of the 1990s. Martin and Sal met Matias. They went to see a band called Farmer’s Manual, from Vienna. On stage they saw a group of men with laptops. With crappy laptops, they say, doing real time sound modifications. Laptop boy band, they call them. Sal, Martin and Matias wanted to start their own laptop boy band. They called it Crowd Formation. Because two is a company, and three is a crowd, Martin explains. And there were three of them at the time. Their first gig was at Windmill Brixton. They had a table, a little contact microphone, and an alarm clock. Their laptops kept crashing. But they had fun. They did realtime sound processing of recordings, live input, songs that they liked…

Terry speaks. A lot of my relationship with Sal was based on him trying to get me to do things that were not necessarily… in character. He explains: you know, I am very much a sort of… home bird. He giggles. My natural environment is very much here. He looks around. Whether it is about an interaction with people or work. We are in his flat in Hackney. And Sal would always try to get me out, he says. We did some very odd things together. He pauses. Like those Drum & Bass parties in a warehouse at 2 o’clock in the morning, where someone would send you a password on Facebook two hours beforehand. And I would be like: I am not going to a Drum and Bass party, Sal. We will be about ten years older than everyone else there. At best. But then of course you go there and that’s not the case. There is always some odd bloke who is in his 60s, with long white hair doing something strange.

Enviroment

And the first night in London, he slept in Holland Park. Gerard speaks: and then he moved to the basement of the Lithuanian House. Ladbroke Grove first, then Notting Hill, then east London, Hackney. The way he saw Sal’s environment was: chaos, creative tools, loads of microphones, things you could write on, places to throw yourself against the wall. That was the environment that Sal wanted to be in. Not a square flat with white walls, he says.

Shortly after receiving the tape with unheard music, Martin visited Sal in his home, in Notting Hill. It was a small place, he recalls. Sal didn’t have many things. But he had a lot of music. His collection blew my musical horizon, he admits. Later, for years, they shared a studio. Martin says: he always filled up the space that he had. A lot of great things, but also a lot of junk. Martin looks back over his shoulder. There’s the garage with Sal’s stuff. Sal was what held the stuff together, he says. Without him it is just stuff.

Laure remembers: we would lend him a house when we’d go off. And then you’d come back, and there was really thick hashish smoke coming from the basement. She giggles. And then you got Sal, in the basement, smoking hashish for the past week or whatever. She says. And exhales: he was like a brother. But life is hard when you don’t want to fit within the system. He couldn’t even find a stable flat. Property prices became too high, she says. And that’s the story for many people nowadays. She continues: but he would always find people who would completely attach to him. Sal had a lot of friends. But he did not have a space. He left his stuff everywhere.

And then there would be times when he was couch surfing, and he would mention in passing that he was sleeping in his garage, Terry says. And you’d think, he adds: fucking hell Sal, you should have called me, you can sleep here.

Gerard remembers: Sal didn’t tell anyone where he lived. At times he was staying in a Violin repair shop in Dalston. With a lot of dust.

P.s. the couch-surfing happened towards the end of his life.

The End

Terry is in his flat in Hackney. He says: life is less good now that Sal is not around. He exhales. He used to come over and he would play records and we would drink wine. He remembers: Sal would say that he liked me better when I was drinking because I was less English. More inclined to talk personally, I suppose, he explains. It was real life. There was this person that would make me do things. Dragging me out for coffee. Making me go out. He became an important figure in my life. A lot of the time we would meet up and talk about how crap life was, and drink coffee, and talk about music and things like this, he says. And maybe I was a buffer between him and all that was going on? He pauses. But also, with Sal, I never really knew what was going on.

And suddenly Sal stopped smoking. He lost weight. He was itchy everywhere. He talked about finding a doctor, Gerard says. He told Sal: find somewhere to live, you are not healthy. It was 2016. And Sal had lung cancer. By then Sal and Gerard had slightly fallen out. I wasn’t in Sal’s good books, he explains. Sal was in Homerton Hospital. Then he got out. He said he was better.

Back at Terry’s. Sal used to come over, he says. The idea was that he would bring a bag of records and play some stuff to me, and I would play some stuff to him. It never worked out that way, he recalls. He would just sit there, next to the record player. And I would sit here, and he would just play me stuff. I wasn’t allowed anywhere near it, Terry explains. In Sal’s selection there was a lot of jazz, a lot of very interesting jazz. A lot of Eastern European jazz I didn’t know of Terry says. And adds: a lot of which he left with me three or four months before he died. He would come over, play stuff, and then ask if he could leave his bag there for the moment. Sal also curated bags of other things that he knew I liked. Terry says. Like Calypso artist Mighty Sparrow, he explains. He had an awful lot of records by him and he seems to have left them here. Terry pauses. A lot of people say they experienced the same thing.

Like Laure. Sal left some record bags with her too. And then, just before he died she visited him at the hospital. She speaks: I remember seeing him there. I am not very good with factual moments of stories. And continues: I took him to the sunshine, we lay in it. It felt like we could be doing a gig. He had lost his hair. He smoked a cigarette although he was not allowed. I just managed to get a bit of sun on his face. He was just deeply in love with life, I think. People said: ah, Sal, he is difficult… But I didn’t have that with him. I was so touched by his life story and how he got here. She means London. How he left Communism for the Western world. The music sort of pushed him away from the rigid regime… She finishes.

And here is Sal, a few years before his death. We talk about escaping. But is this the most important thing in life? You can only answer that once you have experienced it. Was the UK really for me? He asks rhetorically. At the end of the day you learn more about yourself, your limitations and possibilities, and you can assess the price. At the end you find out what kind of picture you want to paint. But that process can take… a lifetime. It is like a boxing match, he adds. You are pushed out then you want to come back and kick some ass.

Simona Žemaitytė is a Lithuanian artist currently working in Naples. In 2011 her work received an award at the 15th Tallinn Print Triennial and was nominated at Sheffield DocFest. She has exhibited internationally, including the 13th Kaunas Biennial; Kasa Gallery, Istanbul; GalataPerform, Istanbul; BAFTA, RichMix, London; Contemporary Art Centre, Galerija Vartai, Malonioji and Kaire-Desine in Vilnius; Riga Cinema Shorts; CreArte (touring exhibition in Pardubice, Linz, Genoa). She is currently doing a practice-based PhD at Vilnius Academy of Arts, where she also teaches.