Virgilijus Šonta’s Photographic Worlds of Non-Normative Disobedience

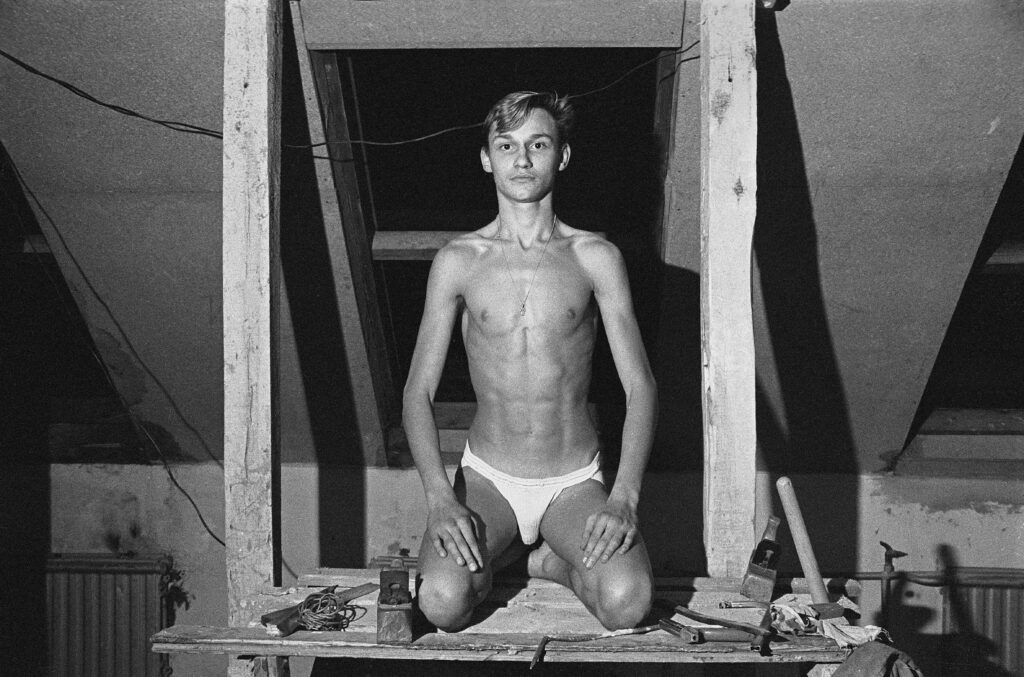

Only tight briefs cover one bit of his otherwise well-built naked body, as the young man poses on a makeshift workbench for Lithuanian photographer’s Virgilijus Šonta’s (1952–1992) camera | fig. 1 |. The action takes place in late Soviet-era ‘downtown’ Vilnius, at the artist’s Aguonų street studio. The sitter, not unsheepishly, strikes his best and most confident pose for a somewhat gawky rendition of ‘the labouring stranger’ erotic fantasy taking place. The situation cannot but evoke a cover shoot for a 1980s do-it-yourself gay mag, a publication that Article 121 of the penal code, which criminalised all sexual relations among men, ensured would never become a reality in Lithuania under Soviet occupation. Virgilijus Šonta did not live to turn the pages or have his photographs in Naglis (1993) and Amsterdamas (1994), two of the earliest LGBTQ+ magazines published soon after Lithuania regained its national independence and scrapped the punitive article in 1993. The previous year Šonta was found murdered in his studio, all valuable equipment stolen from the place that hosted this ‘cover’ photograph. In the end, no one was charged with the crime.

To live a life sexually non-conforming to ‘Soviet morality’ meant being in the perpetual threat of local militia and KGB blackmail, imprisonment or other, less visible but no less damaging forms of social and professional exclusion. These precarious life conditions shaped the covert gay network of chance sexual encounters [among men] behind the Iron Curtain. It is in keeping that Šonta’s activities in this ‘network’ were to be quietly assigned blame for his untimely death, and not the repressive legal, political and social setting, which routinely disregarded lives such as his.

This, among at least a few more dozen until-recently unpublished photographs, found in Šonta’s sheltered hard-to-access archive in Kaunas, suggests an artist whose work was, in huge part, dedicated to the precarious, prohibited, doubled lives, feelings and desires of gay men under the Soviet rule. He gave them a photographic form when simple representation was not an option.

In Virgilijus Šonta’s Untitled (c. 1991) | fig. 2 |, wild plants and trees of the forest surround a young man in the nude. He turns sideways and glances back at the camera with a thin gentle smile. The excess of light to which the film was exposed at the moment of the shot shelters his body. The high contrast pushes the black and white tones towards their limits, light piercing from behind the trees, the lines of his legs and buttocks dissolving into soft, luminous uniform pulsations of an ethereal corpus. He wraps his arms around himself in a gesture ambiguously poised between giving himself cover from the camera’s lens and acting out cautious flirtation. Contours gradually re-emerge as the light travelling upwards reaches his face. The same gleam of light that guards the body from total exposition traces distinct contours of his face, his eyes looking back. Partly in shadow, they deny the viewer’s fixation upon them. The ray of light, the lived events integral part, cuts across the act of taking the photograph, its development process and the glances of its future viewers.

Thirty years after his passing, the latent queerness of Šonta’s photographic work, or more precisely, sexual non-normativity, has not yet been widely celebrated in Lithuania or internationally. Instead, it has seen momentary sparks of interest that would eventually fade without gaining momentum. Until recently, the artist was regarded as a capable yet not particularly remarkable contributor to the so-called Lithuanian School of Photography. A term coined by two Moscow art critics in the 1970s, it described a group of Lithuanian photographers – ‘auters’ informed by humanist, existentialist ideas as well as beatnik and hippie subcultural echoes. Šonta’s work was perceived as slightly off-beat, his most recognised ‘official’ photographic series Lithuanian Landscapes (Lietuvos peizažai, 1974–79), Objects and Forms (Daiktai ir formos, 1979–1991), Flight (Skrydis, 1977–79) veering towards, for the School, an unusually heavy experimentation with light, abstraction and metaphysical symbolism. Art historical write-ups affirm Šonta’s status as the odd one out, scarcely including him alongside his more-famed contemporaries Algirdas Sutkus, Romualdas Požerskis, Aleksandras Macijauskas and Romualdas Rakauskas.

But 2022 feels different. Last September, with protest culture in ascendancy, the first ever Kaunas Pride was as joyful as it was a politically powerful gathering after the city’s municipal administration, run by a strongman with business in Russia, lost his vindictive court case attempting at the eleventh hour, to ban the Pride march from taking place in Kaunas’ city centre. Meanwhile, since Russia’s full-scale invasion in Ukraine, the prejudiced internal politicking against equal rights for LGBTQ+ people has grown quieter and quieter as the broader society comes to terms with the fact that those same bigotted arguments that went down so well for too long dance to the tune rehearsed daily at the Kremlin. The parliamentary vote to write same-sex civic partnership into law may yet be the watershed moment so many have long been fighting for, although in itself a frustratingly limited move towards equality after decades of political setbacks and governmental inaction.

As Šonta’s homoerotic images begin to leak out into the public eye alongside his past lovers’ recollections of their romance, he might become one queer ancestor among very few, a beacon shining through the cracks appearing in the community’s historical erasure. In one rare surviving artistic statement, he wrote: ‘In photography, one comes into contact with the world. To make that meeting real and not apparent, you have to see the world through the eyes of a stranger. And so, it opens up with greater clarity.’ A stranger. Keistuolis is Lithuanian for a stranger, a weirdo, an eccentric or a queer bird. All of these and none of these at once.

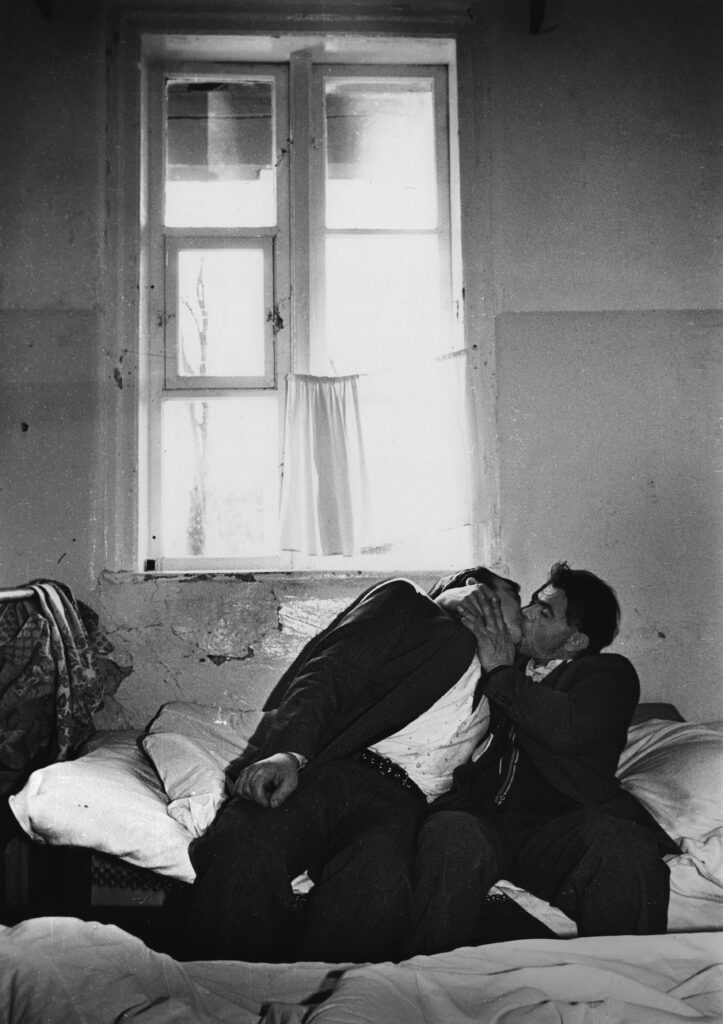

While definitions had to stay fuzzy, the camera could imagine worlds, mediating contact between Šonta’s embodied vision and the world around him. The now-buzzword English verb queering seems almost made for Bodybuilder | fig. 3 |. Sunlight can’t stop the enraptured crowd – predominantly teen & male – from intently gazing at the bodybuilder flexing his muscles down at them from the heights of the podium. The seductive cut out that this image is, intentionally stripping away as much context as possible, relishes the fiction of men unashamedly looking at other men with curiosity and joy. The entertainer bathes in attention, hormones bouncing all over the place with each glance. Šonta’s camera sees the two men locking lips | fig. 4 | in a tight embrace as another guiltless expression of same-sex desire and tenderness, and not as two delirious drunks who lost their bearings. A cyclist | fig. 5 | in his impromptu crop top on a hot summer day stops for a quick break and becomes another character in Šonta’s erotic fantasy of the otherwise dull everyday life in the Soviet 80s. The artist took the normative masculinity he saw around him and rewired it to emanate queer desire.

More than just legitimate, it is ubiquitous, his work murmurs. These three photographs enact what Judith Butler and José Esteban Muñoz termed disidentification but before and outside of the Anglo-American notion’s origin. That is why the significance of Šonta’s archive lies in its sassy disobedience. It refuses to be known to the terms of the ignorant or the hostile. It dares us, this ‘us’ being a multiple entity. ‘Us’ in Western academia it challenges to reckon with a different sensual and conceptual form of queer artmaking – to consider ‘we’ might not have a ready-made framework for its recognition. Radically different socio-economic conditions meant that a particular artistic queer sensibility came about, one that belied a specific subcultural sense of non-normative subjechood under the Soviet colonial regime. To ‘us’, the civic society in the Baltics, Šonta’s work and the drawn-out concealment of his archive speaks about the wider psychic repression of the unwanted parts of our collective past. This repression, paradoxically, carries its traumatic effects we would rather forget into the present. For ‘us’ fighting for LGBTQ+ people’s equality, this unassuming folder of mostly black and white photographs is evidence of tenacious survival and resistance, lives lived in tune with the body and its ‘deviant’, illegalised desires.

Šonta’s photography continuously comes into contact with the world. As one looks at these prints, one might too. In spring this year the Vilniusbased LGBTQ+ cultural-social space Išgirsti held Šonta’s exhibition ‘From the Archives’, presenting unseen parts of his oeuvre in Lithuania for the very first time. With visitors trickling into the Naujininkai apartment-cum-gallery, memories gradually began to flow as generations met, its co-founders Viktorija Kolbešnikova and Augustas Čičelis recounted to me. These photographs, social documents, iconic expressions of irreverent desire, began gaining contours of lived lives again – those of specific places, people, encounters, romantic advances, and break-ups. These histories had been asked to wait indefinitely. Just like Šonta’s photographic worlds, they refused to remain ‘private’.

Adomas Narkevičius is a Lithuanian curator and art historian based in London and Vilnius, currently working as the Associate Curator at Cell Project Space, London. He is interested in nonlinear aspects of historical time as well as the body, sexuality, and the limits of representation. In 2020, his MA dissertation ‘Defiant Bodies: Untimely Art in the Baltics Under Soviet Rule’ at University College London, was awarded the Oxford Art Journal Prize. Between 2017 and 2019, Adomas Narkevičius was Curator at Rupert Centre for Art, Residencies and Education. Among his recent curatorial projects are the solo presentations ‘Tensors’ by Cudelice Brazelton IV, ‘Sideways Looking’ by Peng Zuqiang, and ‘A Glossary of Words My Mother Never Taught Me’ by Renée Akitelek Mboya at Cell Project Space; group exhibitions include ‘Authority Incorporeal’ at Rupert for Baltic Triennial 14; ‘Avoidance’ at FUTURA, Prague; symposium ‘Enacting Knowledges’ at Kaunas Artists’ House and the JCDecaux Emerging Artist Award at the Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius.