Editorial

Edvardas Šumila

Our conversation could only be understood by Čiurlionis, because he painted that moth above the candle. You take one step – enlightenment; you take another – death. And you know what? You are a better poet than a painter. I am not saying you’re no good – but you don’t talk like yourself when you paint. Peace.

Conversation overheard by artist Tomas Terekas while travelling on a train from Vilnius to Kaunas on 5 September 2024.

This overheard conversation quoted above happened at a point when I was thinking about this journal most intensely. There was no title yet, but I was already aware of an underlying tendency to avoid speaking directly, or rather, to avoid pronouncing the main subject of this endeavour, which is, in one way or another, Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis. I think the quote above epitomises how a conversation, which is in an intimately friendly register and also touches upon artistic practice and spirituality, cannot avoid the figure of Čiurlionis since he is so much a part of a discourse intertwined with all of the subjects of this conversation.

I’m trying to set myself a task to go further than just acknowledge this inconvenience of speaking directly; it wouldn’t even be sufficient to go beyond the national status that Čiurlionis, as a figure, has acquired – his transformation into an institution of sorts. In fact, as his 150thanniversary approaches, there is a certain relief in not being involved in any related projects, because, for one, you don’t even believe in the importance of such occasions, but also because it is going to drown the discourse in ever-thickening layers of grandeur. And yet, these tensions create an opportunity to rethink the circumstances critically and through a more personal perspective. We could call this an impossible escape from Čiurlionis, which is precisely where the title of this issue originates. To put it another way, an identity is always a construct, and it is never complete.

The idea of Čiurlionis is, of course, part of a romanticist tradition– where artists become essential national figures. Yet, when an artist’s work has been largely apolitical, their image becomes adaptable to ideological shifts because the realm of aesthetics can be understood as an expanded sense of rationality (as opposed to being thought of as irrational), and so an identity. I’m emphasizing this because there is no real escape – everything here must be immanent. There is a motion towards escaping this dynamic and simultaneously an inability to do so. Thus, the title is both a noun and a verb. Perhaps, then, we do not escape from Čiurlionis but with him.

After reflecting on this, I am confronted with the question: was Čiurlionis himself trying to escape? And maybe, in the end, he did. Or maybe he was always an escapist – both aesthetically and psychologically. I find this notion of escape a far more compelling interpretation than viewing him simply as someone driven by the desire to create a world, though that, too, is evident, as noted by Serge Fauchereau.1 Both readings are possible – but instead of joining the Lithuanian project, perhaps Čiurlionis escaped into a Lithuania that never existed. Hence, in chasing any one version of Čiurlionis, we, too, escape to an imaginary place.

Another important aspect of this inescapability is the omnipresence of Čiurlionis – not only himself but the enduring aftermath of his figure. This makes it possible to view Čiurlionis as a certain lens through which we perceive other practices and histories. He lingers in the background, a presence we try to either discard or embrace. This issue, then, became an opportunity to explore different perspectives – ones not necessarily tied directly to Čiurlionis himself but which, within the constellation of this journal, inevitably take on a new light.

The issue begins with a philosophical encounter with Giuseppe Ungaretti’s famous line, M’illumino d’immenso. Here, the ‘immense’ is explored as both an infinite and unknowable source, one that simultaneously founds and annihilates the self. Dmitri Nikulin analyses how the attempt to illuminate oneself from such a source is both an act of risk and of discovery. He argues that much of Čiurlionis’ work can be seen or heard through the dynamic that Ungaretti’s poem reveals.

Šarūnas Nakas has compiled fragments of Čiurlionis, which, divided into three parts, will be scattered throughout the issue. This is likely the most biographical piece, offering the most direct confrontation with the multifaceted character of national reverence and the complexity in which Čiurlionis has been mythologised and politically appropriated across different eras. Nakas’ voice, well-known for his radio broadcasts (on Čiurlionis, among others) is inseparable from a critical evaluation of the artist’s legacy. It is, therefore fitting that he undertakes the reassessment of Čiurlionis’ legacy – exploring his search for artistic expression, and even his revolutionary activities, which have often been eclipsed by national pride, Soviet ideology, and contemporary cultural branding.

Even more elusive is an encounter with Donatas Jankauskas (Duonis), an artist working with sculpture, installation, and various other media, renowned for his many public art pieces. The entire artistic practice of Jankauskas has its roots in his encounter with Čiurlionis, firstly, as the figure of the art school in Vilnius (bearing Čiurlionis‘ name), and, of course, through the ever-present influence of Čiurlionis in the discourse of art and everyday life. The subtlety of this relationship is unravelled by Asta Vaičiulytė, who interviews Jankauskas, recalling the artist’s ‘Retrospective’ – a milestone exhibition at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius in 1999 – the stories surrounding his artist books Marčiurlionis, and broader topics that situate his connection with Čiurlionis’ figure and reveal an important layer in Donatas Jankauskas’ oeuvre.

Throughout the pages of this journal, you will find a four-part piece by Goda Palekaitė, which reimagines Čiurlionis’ life and work through speculative histories, blending text and visual elements. The first part, ‘I… Typewriter’, serves as an introduction to the cycle as a whole. While it is unlikely that Čiurlionis ever used a typewriter, here, he is given the chance to explore yet another medium, which he struggles to control. The chaotic composition of Palekaitė can also be seen as an attempt to understand the rather psychotic nature accompanying synaesthesia and foreboding mental breakdowns.

The second part, ‘II… Sketchbook’ describes the paintings of Čiurlionis as impressions and allusions, simultaneously capturing the fleeting moment of sketching, the hint of an idea, and the birth of a new painting – both conceptually and visually.

‘III… Landsbergis’ explores Čiurlionis’ legacy in relation to Vytautas Landsbergis, both a figure of Lithuanian politics and a prominent researcher of Čiurlionis. This, of course, places Čiurlionis even more firmly in the national spotlight, imagining him dreaming of his own museum, with Landsbergis as his future acolyte, responding through excerpts from his book.

The final piece, ‘IV… Love’, draws on the affectionate language that Čiurlionis used in his letters to his wife, Sofija Kymantaitė. Through an interplay of Lithuanian and English translations, the recurring sea motif visually symbolises the short-lived moments of their happiness. By the conclusion, this dreamlike vision collapses into a disorientating confusion of words, dissolving any sense of coherence altogether.

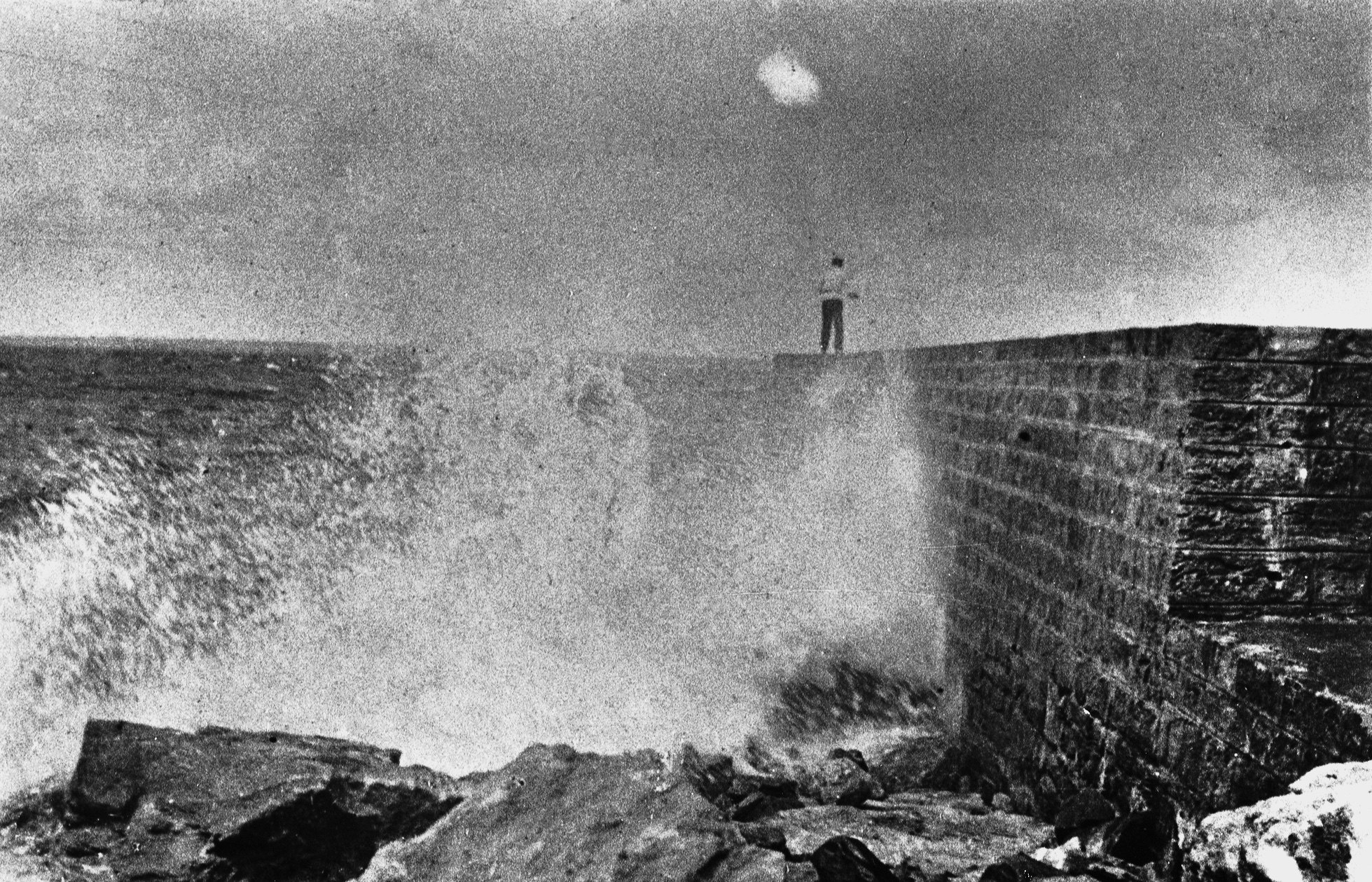

Mirroring these shifting visions, Tomas Terekas’s disruptive collages – featuring water skiers and surfers in a nod to Čiurlionis’ Sonata of the Sea–surface toward the end of the journal, further playing with our sense of narrative that Čiurlionis evokes.

The next conversation takes us to Deimantas Narkevičius’ film Revisiting Solaris, which bridges past and future concerns and anxieties related to technology and artificial intelligence. The curator and film scholar Lukas Brasiskis speaks with the artist about Stanisław Lem’s original novel Solaris and the ways in which Narkevičius’ work explores the novel’s intersections with memory, identity, and technological simulation. While Andrei Tarkovsky’s influential 1972 film is important here as a harbinger of nostalgia — with Narkevičius casting Donatas Banionis, one of the original film’s stars — Revisiting Solaris also invokes a different aspect of Čiurlionis: the futuristic and utopian. Čiurlionis’ early twentieth-century photographs from his so-called Anapa album appear in Narkevičius’ film, evoking the titular ocean, and revealing yet other possible connections that Čiurlionis’ work invites. A selection of these photographs is also published in this issue.

Ben Eastham’s analysis is driven by a different set of connections. In his piece, he dismantles the tendency to focus on whether Čiurlionis was the ‘first’ abstract painter – a claim that risks flattening the richness of his work. The late cycles of Čiurlionis, particularly the Winter cycle, span the fluid boundary between figuration and abstraction not by severing painting from the visible world, but by revealing a cosmos indivisibly alive and intertwined. Eastham, perhaps aided by having encountered Čiurlionis’ work relatively recently, offers a fresh perspective, proving that Čiurlionis can evade the rigid distinctions into which history and often we seek to place him.

The imaginal realm, as argued by Chiara Bottici, neither confines us to a purely subjective dreamscape nor reifies social constructs of ‘reality’. Instead, it shows how images can hold a presence that is both personal and collective, material and spiritual – demonstrating, ultimately, a richer way of being in and perceiving the world. Bottici develops the concept of the imaginal that is drawn from Henry Corbin and Cynthia Fleury; it goes beyond the familiar notion of ‘imagination’ so frequently employed in discussions of the legacy and contexts of Čiurlionis. Here, he is interpreted as an artist who allows us to see the world not as discrete but as a dynamic whole in constant flux. We are invited to access the imaginal through his late paintings Lightning (1909) and Sonata of the Sea (1908).

The late filmmaker and poet Jonas Mekas often invoked Čiurlionis, particularly his music, throughout his work – most notably in his 1972 film Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania. Yumiko Nunokawa extends this connection by reminiscing about her own journeys to Lithuania to discover and explore the music and paintings of Čiurlionis. Contrary to many of the contributors in this issue, Nunokawa has been deeply immersed in Čiurlionis’ scholarship for much of her life – making Lithuania her second home – and giving us the opportunity to see the legacy through her own eyes. Her piece, though less overtly critical, is a testimony to the lasting impact of Čiurlionis’ work, bridging music and mysticism and echoing Jonas Mekas’ poetic evocations – of angels in particular.

In the final piece of the journal, Valentinas Klimašauskas revisits a lesser-known work by Čiurlionis – Composition (1903) – a landscape of birth, transition and greeting. The text posits a liminal scape – a ‘furnace’ – part mouth, part womb, part portal – where language, art and the body converge in shaping new, more inclusive grammars and worlds. Klimašauskas’ writing presents us not only with a certain ur-vision of what a symbiosis between language, body, and symbols might be but also invites us to dream of ‘a (non-)space of Radical Openings and Closures’, a vision of hope in times that are grim and exhilarating.

It is important to acknowledge that by escape I don’t mean turning our backs on things that are happening around us, especially at the time when this issue appears; the climate crisis, a worsening situation of the war in Ukraine, the tragedy of Palestinians in Gaza, and Trump’s return with devastating executive orders and declarations, among so many things. I want to believe that the manifold meanings of escape in this issue can show that escape (and Čiurlionis) can be thought critically and imagined radically, and also to nurture that imagination. We are reflecting on the desire and the need to escape, so we can move forward.

I want to thank all the artists and writers for their contributions – for some time now, they have been collateral to my vision and frustration with Čiurlionis – and I hope this dialogue will endure in other forms. The shaping and refining of this issue would not have been possible without the editorial team, whose good judgment and unwavering support I am immensely grateful for. And to you, my friends, I hope the issue you hold in your hands offers you a worthwhile escape.

- Fauchereau, Serge. Art of the Baltic States: Modernism, Freedom and Identity 1900–1950. London: Thames and Hudson, 2022, p. 38.

More in this Issue

Lukas Brasiskis interviews Deimantas Narkevičius

Table of Contents

Illuminating Oneself by the Immense

Dmitri Nikulin

Fragments of Čiurlionis

Šarūnas Nakas

Hallucinating Čiurlionis

Goda Palekaitė

Another Hundred Years

A conversation between Asta Vaičiulytė and Donatas Jankauskas-Duonis

From Tarkovsky to AI: On the Evolving Resonance of Solaris

Lukas Brasiskis interviews Deimantas Narkevičius

The Sun is God. On the Naturalism of M. K. Čiurlionis

Ben Eastham

Two Fragments and an Imaginal Journey

Chiara Bottici

Yumiko Nunokawa

Vocal Notes for Labouring Worlds

Valentinas Klimašauskas

Sonata of the Sea (Finale, Surf Edition)

Tomas Terekas