I Was Thinking About What You Said

In 2022, to mark what would have been the 100th anniversary of Jonas Mekas, the world and Lithuania have celebrated the life and work of one of the country’s most prominent cultural figures of the twentieth and twentyfirst centuries through Jonas Mekas 100! – a programme of events including film screenings and retrospectives, exhibitions, readings, workshops, new publications and translations of Mekas’ writings, and concerts celebrating the spirit of his works. A global cultural phenomenon in his own right, Mekas is considered by many to be the ‘godfather of avant-garde cinema’.

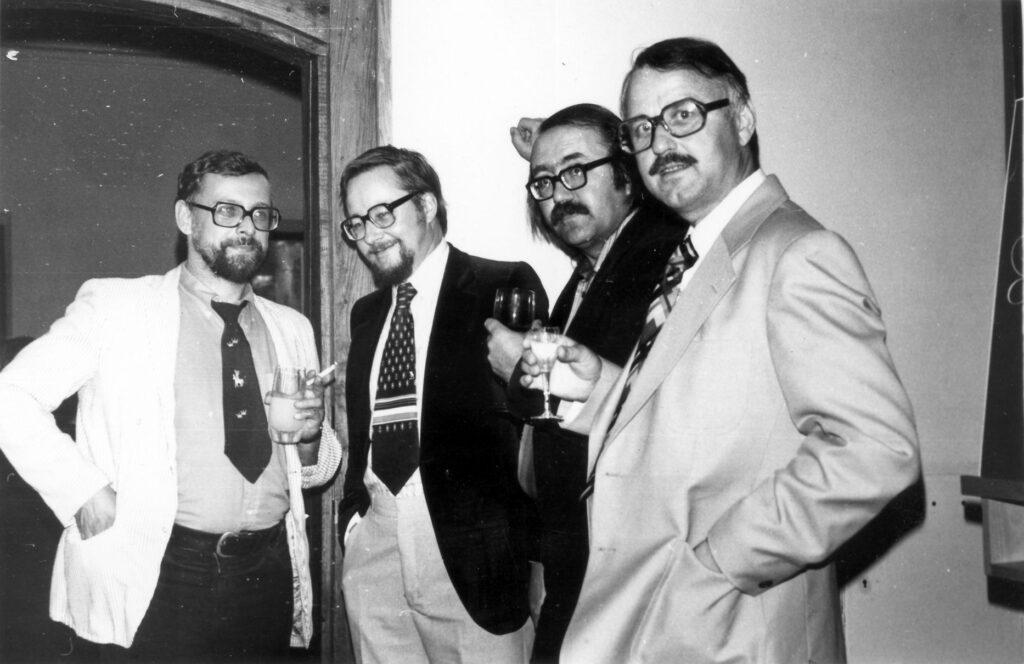

Those who had the opportunity to meet him in person frequently share memories of the informal, friendly and cosmic atmosphere he created over conversations and drinks that were accompanied by his great sense of humour and taste in music. Jonas Mekas grew up surrounded by Lithuanian folk songs, later by talented musicians and celebrities, improvisations, experiments and participated in those performances himself. He was a very musical person, who could play anything.

Through a combination of several coincidences and the alignment of stars, two music organisations – the Felicja Blumental Library and Music Centre in Tel-Aviv and the Music Information Centre Lithuania in Vilnius – in cooperation with the Lithuanian Culture Institute joined the Jonas Mekas 100! programme with the project ‘Temporary Soundtracks’.

Radvilė Buivydienė:

How did you manage to connect the dots between two music organisations and Jonas Mekas and create a project that holds value for artists in both Lithuania and Israel?

Guy Dubious:

It’s always interesting for me to think about the way connections are made, or relations are formed. It seems to me that in most cases these things happen ‘by accident’ but then develop into a narrative as the connection gains meaning and gravity. So, I will try to answer this from both ends of the ladder so to speak.

The accident was a friendly meeting with Elena Keidošiūtė, the Lithuanian Cultural attaché in Israel, on a sunny day just outside the Felicja Center. I was only a few months into my position as director, still deep in the process of learning and getting to know the Center with all the people and things in it.

I was describing the wonderful and problematic history of the place, when all of a sudden Elena said something about Mekas’ centennial celebration the following year, and within the same breath dismissed it as not exactly being in the field of music. ‘Mekas!!! This is exactly what I want to do… no clue what or how,’ but I remembered a night in New York in 2011, at the Anthology Film Archives, where I attended an event titled ‘Mekas’ Birthday’. I was expecting a cinema night with some kind of surprising screening but nothing of that sort happened. Instead, arriving at the lobby, already crowded with people, a drum kit awaited in the corner, with all sorts of musical instruments and gadgets scattered around it. Not long after, someone began arranging the equipment, and we realised another plan was taking place. I was happy to have my small tape recorder with me. Meanwhile, in the lobby people were conversing, some faces were familiar from Mekas’ movies, others just felt so because of the generous spirit of hospitality. It was a strange and unique feeling of stumbling into a party half invited. Everybody seemed to know one another already. Still, we felt welcome, and as if anything could happen.

The performance was insane, it was the first time we saw Dalius Naujo, and I also got it on tape.

The image of that scene is indelibly imprinted in my mind, with the impressions of it still ringing in my ears. Sitting on the bench with Elena I thought how great it would be if we could have an event like this at Felicja. Something that will advocate our presence with the famous ‘Now We Are Here’.

So, the project, you might say, was sparked by the recording, emotionally and musically of that night. It was up to me to begin working those lines of flight and form a project that would migrate Mekas into music.

The trouble was the question of affiliation between Mekas and the respective organisations – between his work and music. These relations can be manifested in different ways over the course of his films, projects and the social activities he was creating and involved with: the relations between sound and image in his diaries; the role of music in the notion of expanded cinema; his own musical aspirations manifested in his writings; and his late turn into installation involving compositions and sound pieces. We were curious about the possibility of imagining Mekas as the composer or the musician, in some parallel universe. The idea was that this Mekas wouldn’t be that much different to the one we are familiar with but instead of making films he would be making sounds.

Such a parallel universe indeed existed to a degree with Mekas but also with other filmmakers in his milieu; Tony Conrad is a great example of someone who made the crossover between music and film. Watching Mekas’ 1968 film Walden again, from this new perspective, it can be experienced as precisely that – a line of flight forming between fragments of light and noise. What could become of Mekas if he was situated within the field of music making? This question became the setting stone of the project.

Mekas spoke of himself as a diarist – a gatherer, a note-taker. Obligated to the significance or the poetics of the encounter. Filmmaking as a process of mattering time. Films made not of a narrative, a story, but of durations, of movements that are introduced and reintroduced through the art of filmmaking – a musical score for light and people. The intuitive manner of composing those images with his Bolex, the poetic relations between the cinematographer and the camera expressed, for example, in the use of variable speed and double exposures. These could be thought of as gestures of play that form the modulation of exposure in a similar way to the variations in sounds created through musical play.

The critical axis that both organisations and Mekas are related to, is the archive. Felicja holds the personal archives of early composers in Tel-Aviv. Given the historical situation these composers, musicians and music educators who donated their personal archives to the Center in Tel-Aviv, were all immigrants from Europe. All working in the tension between the ‘new’ not-yet-home and the tradition of the old home that most of them could not return to, which is not dissimilar to Mekas’ situation.

The archives of the Music Information Centre Lithuania were established in 1946 by the Lithuanian section of the Music Fund of the USSR. This collection consists of the sound archive of classical and contemporary music by Lithuanian composers and the library which holds published scores, as well as books, periodicals, photographs, etc. The collection of scores by Lithuanian composers is the most significant and largest archive of its type in the country.

For both organisations, the archive is seen as a source of creativity, it is not an end point but rather a foundation from which new music can emerge. I considered this approach very much in line with Mekas’ approach to his own archive. It is not so much the documentation of his work, but the building blocks which constitutes his creative act. In that sense, the archive is the meeting point of both organisations and Mekas. We want it to be a celebratory meeting, a gathering of different beings and approaches, an expansion of what can be thought of, or become with Mekas’ work.

RB:

Lithuanian artists have been strongly influenced by Jonas Mekas’ films and poetry. Composers have incorporated his texts in their works and field recordings or conceptual walking projects have gained popularity in Lithuania. Sound artists have used recorders for documentation, albums or art installations just like Jonas Mekas used his camera. Do you think these kinds of sound projects fit into your imagined parallel universe?

GD:

The link you propose between Mekas’ use of the Bolex camera and the practice of field recordings in the contemporary situation, is important. They share something in common in their misuse of certain practicalities, supposedly inherent to the practice. Field recordings have gone from being a practice of surveying culture or natural phenomena – you might consider music anthropology at one end of the scale and soundscapes concerned with the natural world at the other end. In both, the paradigmatic position of the recorder is supposedly impersonal. The recorder is expected to be a reliable technician, operating the machines to deliver the best representation of whatever the subject is. Field recording today has become an interesting playground for many artists, and the issue of representation is no longer the main focus. Field recording became a way of interacting with the sonic, a way of engaging with the world as well as with the medium itself. Field recordings became poetic means.

This is a critical point, I believe, for the understanding of both sides of this parallel universe – Mekas and the contemporary world of music and sound artists. To grasp that Mekas’ attitude towards the world, as a continuous happening, could not have been developed without the relations forming between him and Bolex camera. Such relations cannot be grasped solely as means to an end, Mekas is not merely documenting. Mekas is very much a participant within the situation he is filming, he is dancing with the camera, and with the other movements that intersect the Bolex-Mekas world. Field recordings today mark a performative practice rather than an academic one.

RB:

What is the idea behind the open call for ‘Temporary Soundtracks?’ What kind of material will be used for these soundtracks?

GD:

The open call creates an opportunity for artists to work with selected material from Mekas’ film archive, composing soundtracks for it. The soundtracks will be as temporary as the happening itself.

However, ‘temporary’ does not just refer to the matter of time, or shortness. It is also about the moment, the irreducible moment to moment, the endless effort of experiencing, living and re-living, which Mekas’ films have always been about.

‘Temporary’ also relates to the question of sound in general, being that which dissipates upon emergence; and the question of sound within the particular relations it forms with the moving image.

These are some of the daring points we hope to explore through this open call: the potential for expansion within the relations between sound and image, and how sound can become an agency that modulates the different aspects of the screening. For example, it can explore absurdist responses between the archive and sound making. It can open the films up to improvisational practices of all kinds. I guess there are plenty more we haven’t yet thought of.

In short, the idea of ‘Temporary Soundtracks’ is to side-step the classic soundtrack position of amplifying the visual content, and to explore their encounter as, more or less, equal forces.

When I thought of the idea of temporary it was immediately related in my mind to the celebratory aspect found in much of Mekas’ work, and the general attitude – his famous ‘Now We Are Here,’ as perfect example. It is not necessarily a joyful celebration, in fact to a degree it is not even emotional. It is rather a point from which to cherish whatever and whoever is here now: a dare to embrace the existing sense of fragility and be indebted to the loss.

Radvilė Buivydienė has worked in the fields of music management, publishing, communication and music export for more than 13 years. She started out as a cultural journalist and producer of various music festivals, events, projects and music albums and is now the head of the Music Information Centre Lithuania – the country’s leading nonprofit NGO within the field of music.

Guy Dubious has been developing his music and art practice with tapes and recording machines from an early age. In 2008 he founded Zimmer in Tel-Aviv, an autonomous community space for experimentation in art, mainly in the fields of sound and music. In 2014 he began researching the poetic mechanics of recording at Birmingham School of Art, in the UK, where he completed his PhD. He is currently the head of the Felicja Blumental Library and Music Center, in Tel-Aviv.