On the Enduring (Mythic) Legacy of Twentytwentyone

Myths and rumours are rife throughout the world of music and sound art. It is often said that, if Woodstock had actually hosted the number of people who subsequently claimed they had attended, then the event would have been four times the size! A similar sort of mythos surrounds the (retrospectively) seminal Lithuanian sound group Twentytwentyone: for although their performances have become the stuff of legend – in the course of researching this journal, I was told by three different people that their inclusion was ‘imperative’ – this assessment stands in stark contrast to that held by the group themselves. And indeed, perhaps this more honest and humble assessment is also something of a myth, and has as much to do with the subsequent careers forged by each of the group’s four members. Irrespective of where the truth lies within this spectrum of opinions, there is little doubt that Twentytwentyone left an indelible mark on the work of its four founders – Antanas Dombrovskij, Lina Lapelytė, Vilius Šiaulys and Arturas Bumšteinas – as well as on the wider experimental music scene in Lithuania. In order to gain a deeper understanding of this impact, I interviewed Arturas Bumšteinas across several email exchanges, asking him about the group’s origins, its influences, as well as with the obdurate legacy of these myths.

Damian Lentini:

You have always drawn upon such a wide variety of musical sources. Who were your inspirations growing up, and did these influences inform the founding of Twentytwentyone?

Arturas Bumšteinas:

From the age of ten I was already going to the Vilnius Jazz festival, which always had a diverse programme, including the most extreme forms of free jazz. Then in 1994 I saw a large touring exhibition called the ‘Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus art collection’ at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius, which showed me the direction I wanted to move in with respect to my own work. Another major influence was the Lithuanian Open Society Foundation, which was founded by the great humanitarian George Soros. It was here that I was able to access the internet for the first time, and they also had a great phonotheque and videotheque with very well curated content. The same foundation enabled Šarūnas Nakas to organise Musica Ficta in Vilnius: the first real international festival of contemporary music where I heard Bang on a Can play Hoketus by Louis Andriessen, which really impressed me. In 1997 I got my hands on the five CD box set Tulpas compiled by Ralf Wehowsky, which introduced me to a very wide spectrum of 1990s experimental music, as well as pointing me towards emerging digital approaches to music production (even though I was still mostly drawn to experiments involving audio tapes and things involving speech). I also participated in the Mail Art movement and if I’m not mistaken I’m the first Lithuanian composer to make music using the internet to gather sounds from people. Later, when I started playing in festivals abroad with my laptop (electronic musicians all lived in ‘Laptopia’ back then), I shared the stage with so many greats from the experimental electronic music scene. The ones that most impressed me were the Finnish duo Pink Twins; Pan Sonic; Cellule d’intervention Mentamkine; Pure (and almost everything else on the Mego label); Farmer’s Manual; Carsten Nicolai; Supersilent; Merzbow; Scanner… these are the names that come to my mind now, but of course there were dozens of other influential acts. It’s also important to note that the electronic scene was only one of my diverse musical interests – my favourite composers then were Robert Ashley and Morton Feldman, and I was also very interested in contemporary dance and performance art. This all influenced the sort of art I wanted to make and our laptop quartet was mostly an outlet for digitally processed sound experiments…

DL:

Can you describe the Lithuanian sound art scene at the time of the group’s founding? How was it different to today?

AB:

The sound art scene at the beginning of the twenty-first century was ok. There were interesting people making music, doing fun festivals from time to time, and organising performances in both interesting locations and quite ordinary bars and cafes. Actually, the great Café de Paris in Vilnius was very welcoming to anything new and experimental. In contrast to then, when the scene was almost solely male-dominated, nowadays there is a big sense of diversity in terms of both content and creators; and the funding situation is also much better. Vilnius is actually a very cultural city, with many open-minded institutions and enthusiastic young people who are both well educated and well travelled. I guess it will remain so as long as we remain a western democratic state, and there will be less marginalisation in the social and cultural spheres.

DL:

So how specifically was Twentytwentyone founded?

AB:

In 2005, when I was studying at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theater, I began travelling to festivals with my own experimental music. I saw plenty of great electronic music acts that inspired me to create a group of my own; one which would merge Laptopism with the academic music avant-garde. For the first few months, the group was called Laptop Quartet and I chose to use my computer as an instrument, as most of my friends were also making and performing music in this manner (the modular synth scene was yet to arrive). I wanted the group to be a quartet in reference to this well-recognised form of classical chamber music; a kind of continuation of the ‘haus musizieren’ tradition. I invited my good friend and experimentalist Antanas Dombrovski to join, as well as a young and talented underground ambient artist Vilius Šiaulys, and a violin student at the Music Academy named Lina Lapelytė whom I met in the corridors for the first time and whose Duchenne smile and irresistible charisma I fell for. We started rehearsing in an underground bunker, which had been converted into a sound studio and rehearsal space by Antanas.

DL:

So what precipitated the change in name to Twentytwentyone? And what were your initial aims for the group?

AB:

As I mentioned, we were first called Laptop Quartet, because I wanted to merge old and new, but then I thought that this was a rather primitive idea, and that too much attention was focused on the technology. So I then came up with the name Twentytwentyone for three reasons: it still had the old/new element in it (although not as explicit); we were all around about this age when we founded the group; and lastly, we decided that we would only be active until the year 2021 and would then quit to pursue other projects (actually, we disbanded the group much earlier). The main aim was to compose adventurous music programmes and to tour the international festival circuit. However, we didn’t have a promoter, and many of the heads of new music in Lithuania didn’t really think much of us. So we were left hanging by a thread in the beginning and would only receive a couple of offers each year. Now I hear some people say that our performances in Vilnius were legendary… but this of course is mainly said by people who didn’t attend the concerts themselves.

DL:

Can you speak a bit more about the specific ‘instruments’ you used, as well as the relationship between analogue and digital?

AB:

Back when we were founded, we used a whole variety of Windows-run PCs; basically we were young and poor and could not afford the computers we really wanted. A few years later we were using Apple Powerbooks, but still reliant on software like Ableton, Reaper, Adobe Audition etc. This is what I mean by Laptopism: a genre of music which is defined by the way music is made and performed. It’s not a musical style like Minimalism of course, but refers more to the involvement of technology in the tradition of music. For us, the laptop was basically a tool to play back files, although the files themselves were not often digitally generated. When trying to define Twentytwentyone’s sound, I’d say that it’s inputted acoustically, processed digitally, and played back as a sound file or set of files. Or sometimes (quite often in fact) it’s processed digitally live.

DL:

How did you approach the idea of composition and collaboration?

AB:

The first piece we played together was Cornelius Cardew’s Treatise and I remember that the rehearsals for this were really exciting. From the very start, I knew that the group would be dedicated to electronic renditions of various graphic scores, and I chose these on account of their accessibility for non-classically-trained musicians. Most of them can’t even be called scores, but rather trampolines from which you launch into your own personal interpretations. The meaning of the various signs can be determined among the group and this democratic approach was really attractive to me. While working on Treatise for example, we would each choose four pages for our solos. During these moments, the others would play accompanying sections, or we would divide different parts of the score between one another. We did not so much discuss the overall sound, but rather left it to chance to decide. When the result was too muddy we would go for a more organised tactic of sound formation. By ‘sound’ I of course mean the sonic quality of the final result, the aesthetic objective.

DL:

What drove your selection of the scores? Was there something about these works that made you think that they would be interesting to be reinterpreted via laptops?

AB:

As I mentioned earlier, I was interested in using graphic scores because they were very accessible and open for interpretation. I was doing research in this field and I found many composers (both older and contemporary) working with graphical notation – but for the first performance I chose several classics of this genre, as we were playing at a contemporary music festival. If we were debuting in a club, I guess I would have chosen a completely different set of scores. But most likely Treatise would have featured anyway, as it’s a real masterpiece which has been interpreted in so many different ways by people around the world (just like Terry Riley’s In C).

DL:

What did each individual bring to the project? How did you differ from one another?

AB:

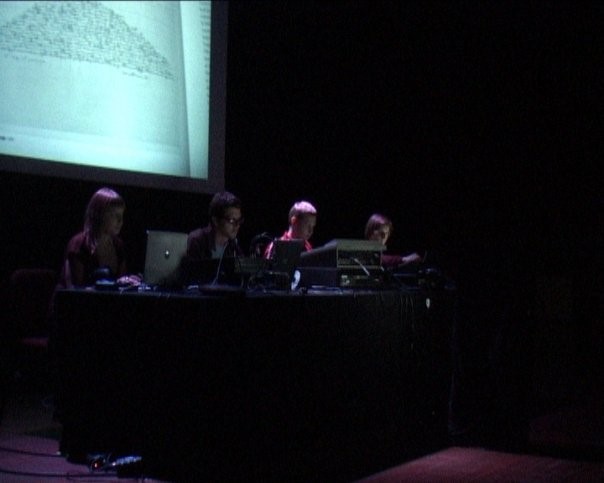

I was mostly responsible for the sounds that would be synchronic and in time with the score’s timeline. I wasn’t afraid to be illustrative because I wanted the audience (who could see the scores projected on the screen above us) to connect the music to the visual figures that littered the scores. Antanas was mainly into heavily processed sounds and especially pulsating ones. Vilius is a drone/ambient artist, so I would often argue with him, trying to convince him to break with his continuum and not to drown out everything in one flow (I behaved like an annoying dictator sometimes). Lina would do the most minimal things, tiny sounds, sine waves, some clicks and bleeps. I remember we all used non-generative software, just playing sound files – wave forms – with the most obvious commercial software available. We weren’t really computer wizards, maybe that’s the reason why we later started expanding our instrumentation: I’d start using guitars and objects, Antanas would circuit-bend old minikeyboards, Vilius would use samplers and other various live electronics, and Lina would take out the violin more often.

DL:

Tell me about your first concert. What happened after that?

AB:

Our first concert was in late 2005 at the Jauna Muzika festival that took place in Vilnius’ Contemporary Art Centre. We played a programme of graphic scores by the Lithuanian composer Vytautas V. Jurgutis; a conceptual visual score by architect Tomas Grunskis; James Tenney’s piece Never Having Written a Note for Percussion; Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Studie II; and of course Cardew’s Treatise. This caught the attention of Lieven Bertels, who immediately invited us to play at the Holland Festival (he was one of the artistic directors of the festival). This invitation wasn’t received well by the new music community in Lithuania, because they wanted to promote their own artists, but instead, completely out of the blue, our strange, shy, very young laptop-gazing quartet got to play at a big festival in Amsterdam. Our appearance wasn’t mentioned in any Lithuanian press, even though it was the first time Lithuanian experimental music was presented in such an ‘upper class’ context. Later, we played at festivals like Skanumezs in Riga, Cut’n Splice in London (which was broadcast on BBC Radio 3), Concertgebouw in Bruges, iFEM festival in Northern Lapland, Exposition of Music in Brno, as well as some smaller gigs at galleries. We also released some of our music online and created a split LP. We would later incorporate early experimental films such as Marcel Duchamp’s Anemic Cinema (1926) or Viking Eggeling’s Symphonie Diagonale (1924) into our programme; treating them as moving graphic scores and trying to catch the changing, fleeting, abstract forms and sculpt them in sound. However, as we were not actively promoting our work, there were not really that many Twentytwentyone concerts. We slowly began to become busy with our own work, and the band dissipated.

DL:

Could you speak some more about the relationship between the visual and the aural in the group’s work?

AB:

This was during a period in my life when I thought that translating visual information into the domain of sound was a really interesting idea. This act of translation and the possibility to see/hear the transformation process seemed like an interesting thing to behold. I had a leaning towards the classics of experimental cinema because I loved analogue film. I loved the celluloid grain and grit; Jonas Mekas for me was the main guy, so anything from his Anthology Film Archives could be considered by us. Later on, we also did some performances using the work of visual artists such as Christian Frossi. He gave us his silent film Ricostruzione approssimativa del Manifesto Spazialista (2007). And if we were still around today, I imagine that we would be working mainly with contemporary visual artists… or even making our own graphic scores. Who knows…

DL:

What about the legacy of Twentytwentyone? Can you speak briefly about each of your careers after the group wound up? How has the project impacted each of your practices?

AB:

Well, Vilius and Antanas keep on creating their incredible electronic music, which should be featured at leading festivals around the world. But neither of them has the ambition to promote themselves, so their work will probably never reach international audiences, unless some sort of miracle happens. Lina went on to become an international star in our field. I really mean it – she’s a gift to the world. In twenty years she will be as big as Laurie Anderson or anyone from the eye-level shelves.

Damian Lentini is a curator at Haus der Kunst in Munich. He obtained his doctoral degree on contemporary art, curation and museum studies at the University of Melbourne in Australia and lectured extensively on the history and theory of modern and contemporary art. After permanently relocating to Germany, he worked on various exhibition projects in both Berlin and Munich, including being awarded a Goethe Fellowship to contribute to the landmark exhibition project ‘Postwar: Art between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965’ (Haus der Kunst, 2016). Since then, Lentini has been extensively involved in major exhibitions and publications featuring El Anatsui, Phyllida Barlow, Kapwani Kiwanga, Sarah Sze, Lina Lapelytė, Sung Tieu, Arturas Bumšteinas, Harun Farocki, Jörg Immendorff, Khvay Samnang, Raqs Media Collective, Forensic Architecture and Dumb Type among others.