Post-Soviet Gendered Soundscapes: Lithuania

Composition: ‘Bolt’as’

‘Egidijus accepts my Bolt taxi ride request. It takes him 15 minutes to arrive at Vaišvydava, where I have been waiting. We both turn to our phones to verify the booking: I check the number plate of his car; he checks my name. Our ride begins. Egidijus is unreserved. He talks about his “real” job – the family business that hasn’t been doing well since the pandemic. We discuss the politics of “Bolting”, the rise of the gig economy in Lithuania and issues with unionising. As our voices momentarily align, the soundscape of the taxi ride unfolds with a shared dissonance against free market systems, capitalism and our support for workers’ rights. The tone, however, changes abruptly.

“I really do not understand why women are allowed to drive taxis”, Egidijus asserts. He is outraged by “young” women taking on part-time “Bolting”: “I would not want to see my wife or my daughter driving taxis at night, or day! It is just not the right profession or a hobby for them.” He pauses. “What if the car breaks down, what if a marozas [aggressive type] disrespects you, how will you duosi jam į snukį [punch his face]?” He pauses again. “If anything, we need less women in front of the wheel.” I try to confront Egidijus’ fury. He has, however, stopped listening. “All men think the same”, he asserts and silences the space. The soundscape of the taxi slowly develops a darker tone and timbre. My voice, for Egidijus, becomes noisy, an intrusion. To silence it, he blasts the volume of the radio. Bonnie Tyler’s classic Total Eclipse of the Heart feels somewhat uncomfortable. The ride ends.

A message from Bolt pops up on my phone: “Would you like to tip the driver?” I click 1 Euro. The driver responds with a smiley emoji.’

Introduction

‘Bolt’as’ is a sonic note, an encounter, a composition, an experience, a soundscape, a moment, a space, a time, a commonplace. ‘Bolt’as’ is an auditory ‘detail’, taken from ‘“Post-Soviet” Gendered Soundscapes’ – a sonic arts and research project I have been developing since the start of 2022. The term ‘soundscape’, introduced by the acoustic ecologist and composer R. Murray Schafer in the 1970s, is often understood as an acoustic totality of a lived sonic environment, including its noises, music, nature, and technologies.¹ A soundscape can also be conceptualised as a context that surrounds and unfolds in ‘complex symphonies or cacophonies of sound’.² For Jonathan Sterne, a soundscape ‘speaks to the physicality of sonic space’ moulded by historical, social, cultural, political and technological processes.³ Whether material or abstract, the soundscapes of the past and present serve as a fabric to our lived environments, shaping how spaces and places are remembered, understood, produced and experienced.

As a practising sound artist and researcher committed to feminist thinking and practice, I am interested in what we might discover if we listen, rather than look, for gender in our lived environments. In this entry, I turn my attention to what Christine Ehrick calls ‘gendered soundscapes’⁴ and explore how sound and gender are projected, performed and embodied in my immediate ‘Post-Soviet’ locale – Lithuania, where I was born and grew up. Thinking about soundscapes as gendered and gendering, Ehrick argues, can help us understand how ‘power, inequality and agency might be expressed in the sonic realm’.⁵ Listening to our lived soundscapes, in this sense, can help us grasp how sound contributes towards the production and embodiment of socio-political differences, including gender, sexuality, race, age, and ethnicity, in lived spaces.⁶ As the products of histories and ideologies, spaces, to use Doreen Massey and Henri Lefebvre’s thinking, are utterly political constructs that change and shift over time.⁷ Spaces, in this sense, as active channels of power, are able to enforce silences, construct exclusions, generate resistances and offer agencies, both visually and sonically. In this entry, I tune into the auditory dimension of space and explore how gender, sound and space might interrelate. I conceptualise their relationship as a live material dialogue, through which gender hierarchies, norms and subversions might be projected, enacted, maintained, embodied, internalised, disputed or resisted.

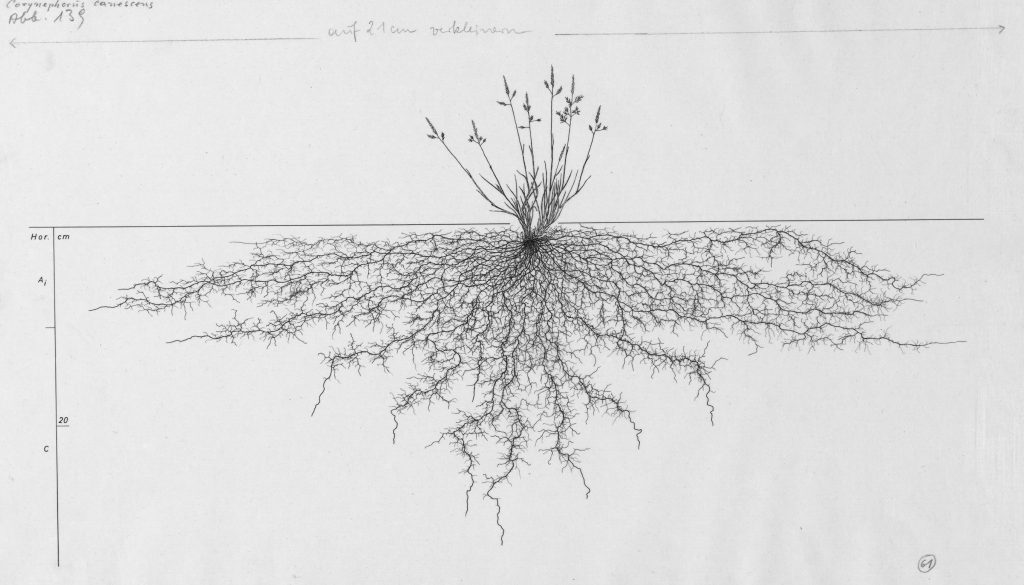

Led by feminist curiosity as well as my own lived experiences of growing up as a ‘girl’ and later a ‘woman’ in the newly reestablished Lithuanian state, I am interested how our public and private spaces have continued to categorise gender roles since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, and how gender has been represented, performed and experienced spatially through the sonic. What power imbalances, tonalities, harmonies and discriminatory dissonances might we discover, if we listen to voices, noises and silences that unfold in the continuum of Lithuanian lived soundscapes? I explore these questions and this precise geopolitical context through my sonic arts practice. Using field recording, note-taking, sound scoring and composing, I listen out to everyday lived public and private spaces and question how different thresholds of sound contribute towards the production of social and political space, where prescribed gender roles and binaries continue to resurface and prevail.

Arriving from Pauline Oliveros’ methodology of ‘Deep Listening’, I listen openly and globally.⁸ I tune into the auditory dimension of structural inequalities, stereotypes as well as patriarchal family systems and attitudes. I listen out to the omissions, the silences and the gendered hums. I also search for auditory subversions, critiques and moments of resistance that obstruct the dominant masculine ideals and structures. The process of global listening in the context of listening for gender is ongoing and undertaken in-situ. As argued by Järviluoma, Moisala and Vilkko: ‘when studying gendered lived spaces, it is […] necessary to interpret the sounds situationally. […] We need to study the subjective and shared meanings of sounds, in situ and dynamically’,⁹ accounting for the peculiarities of each context and its ‘sound effects’ (l’efts sonaires)¹⁰ – the cultural, spatial and perceptual contingencies of sound. The remainder of this entry offers some initial reflections on sound, gender and the ‘Post-Soviet’ Lithuanian space, alongside written scores and encounters, during which, noise, voice and silence were listened to and embodied as the constitutive elements of gendered/ing soundscapes.

Composition No. 2: The Kitchen

‘Dinner is about to be served in the kitchen. She will not sit at the table. She will continue to wash the dishes, pass the salt, slices of bread and sausages from the pan onto his plate, if and when needed. The plate, fork, and a knife have already been laid in its usual arrangement – the usual spot. He seats himself at the table. The TV is on, and it is loud – it is the way he likes it. He begins to eat; he listens to the news; he and she are in silence.

The room, however, is not silent, but filled with a wide spectrum of noises. The sounds of the dish washing and cleaning, a gruesome news report emitting from the TV about a car accident that took place in the last 24 hours and the general hum of eating and movement slowly fill the domestic soundscape. “I have a good one”, he adds to the cacophony. She does not respond. He proceeds: “Why do women wear high heels, make-up and perfume?” No answer. “Because they are small, ugly and smell bad!” he laughs. She responds with a quiet smile. He finishes his meal and leaves the room. She picks up the plate and leftovers from the table and puts it all in the sink. The noise continues.’

Sound and Gender

In her essay ‘The Gender of Sound’ (1995), the poet Anne Carson traces the history of gendered sound. She writes that since classical antiquity, ‘putting the door on the female mouth has been an important project of patriarchal culture’, as ‘women’s’ sound only leads to ‘monstrosity, disorder and death’.¹¹ Reflecting on the feminine/masculine binary parameters, the author acknowledges that Western civilisations have continuously admitted women’s sound as lacking ‘the ordering principle of sophrosyne’¹², deficient in moderation, harmony, logic and order. Since the ancients, Carson writes, ‘women, calamites, eunuchs and androgynes’ have been understood as ‘deviant from or deficient in the masculine ideal of self-control’¹³ because of their ‘high pitch’ sound and the ‘bad’ (‘feminine’) tones. In order to maintain the order and reason, Carson reflects, women’s ‘disorderly and uncontrolled outflow of sound’ had to be regulated and kept being silenced.¹⁴ ‘Silence’, she continues, ‘is the kosmos [order] for women.’¹⁵ Carson’s observations resonate with those of the writer Anne Karpf, who also reflects: ‘if silence is the ideal for women, then any talk in which a woman engages can be too much’¹⁶, suggesting that women’s sound, when in use, is always already too excessive and undisciplined – it disrupts the structures and spaces of reason. Marie Thompson further asserts that the category of ‘woman’ has been ‘met with fear and degradation; she has been the perversion of reason, morally bankrupt and the abject defilement of the sacred and the pure’. ‘A woman’ should be looked at, not heard.¹⁷ Carson, Karpf and Thompson’s accounts demonstrate how the noises, silences or voices produced by some bodies have been continuously subjected to erasure, undermining, fine-tuning and tweaking in line with universal masculine ideals.

The relationship between sound, gender and space is, indeed, one of entanglement. After all, sound is not a static materiality or medium. It grows, transforms and dissipates according to the physical as well as broader social, cultural and political contingencies. Gender too, as a socially constructed (and performed) category, to follow Butler, shifts and transforms according to historical, social and cultural practices.¹⁸ Thus, how sound might be gendered will depend on the context in which gender is produced, understood and experienced. In addition, while sound may shape gender and gender may shape sound, the relationship between the two, as Marie Thompson argues, is ‘not simply of mediation’,¹⁹ but one of relationality. As Thompson further asserts: ‘gender is constituted “with, through and alongside” the sonic.’²⁰ When thinking about sound and gender in the context of soundscapes (including its ‘sound effects’), it is important, thus, to consider the relationship between sound, gender and space as active, ‘multidirectional and co-productive’,²¹ rather than causal. After all, according to Blesser and Salter, ‘a soundscape is a living organism with a personality that arises from the composite behaviour of the inhabitants.’²² As lived materialities and social constructions, sound and gender oscillate and fluctuate in time, consequently shaping the ‘life’ of the soundscape, how it might be represented and embodied.

Gender & ‘Post-Soviet’ Lithuanian Soundscapes

The so-called ‘Post-Soviet’ Lithuanian soundscape could be conceptualised as a living compound structure reverberating in knotted cacophonies and interwoven euphonies. Over the last two centuries, Lithuania has been subjected to harsh political, social, cultural and economic transformation, most recently under Soviet rule. The state was occupied and annexed during the Second World War and only regained its independence in 1990. Lithuania’s accelerated transition into Western democracy has resulted in the production of hybridised socio-political soundscapes. The sounds that permeate lived spaces, as a result, have become entangled and complex. They are attached to both, the West and the East; they are hyper-capitalist and neoliberal, while simultaneously, they are still tied to the yet-to-be-processed communist past. While accelerated in their cacophony, heterogeneity and capitalist reality, the soundscapes of ‘Post- Soviet’ Lithuania continue to oscillate between oppositional thresholds and extremes, between past traditions and contemporary realities, often exposing their uncanniness and eerie discomfort of having to adapt and change.

The ‘uncanny’ nature of the ‘Post-Soviet’ Lithuanian soundscapes can also be heard through the dimension of gender. During the Soviet regime, the ideology behind a ‘Soviet woman’ and the ‘Soviet family’ promised an erasure of gender differences as a way of emancipating women and offering equality. As the right and obligation to work was at the core of the socialist values, women ended up undertaking waged labour as ‘working women and mothers’ as well as performing the usual (unpaid) social reproduction work, such as housework, looking after children, husbands and grandparents. In this sense, within the Soviet gender hierarchy, women were considered as both, ‘breadwinners’ and ‘worker-mothers’.²³ The reality behind the superficial image of women’s equality, advocated by the Soviet regime, was, however, rather different. According to Olga Voronina, women were the domestic slaves of socialism: ‘their labour held up our extensive economy for many long years at a low cost […]. On the exploitation and appropriation of women’s unpaid labour in the family, the family has maintained itself as an institution for the perpetuation of labour-power,²⁴ as has the patriarch-state, which devours that power.’ If anything, the role of women as ‘paid workers, wives/partners, (lone) mothers, providers of care/health/education, and participants in public life’²⁵ only deepened the already ingrained inequality.

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the abrupt transition into the Western democracy, the newly established independent Lithuanian state underwent a hyper-capitalist re-organisation of life. Lithuania was quick to adopt neoliberal free market systems, consequently pushing the country into an economic crisis and mass unemployment, which resulted in the ‘feminisation of poverty’.²⁶ The category of a ‘woman’ during the early years of independence was quick to reverse back towards the old patriarchal gender regimes, albeit set within the framework of the ‘new’ family ideology. Women ‘could become women’ again, do ‘womanly things’ – things that are closer to ‘their nature’ and ‘nature’ more broadly – be housewives, child bearers and be beautiful. While Soviet women were seen as lacking feminine traits, the women of the new independent Lithuanian state, now freed from the Soviet regime, could be ‘themselves again’ and return to their ‘naturalised femininity’.²⁷ Within the liberalised free world, ‘stay-athome- mothers’ and wives, as a result, returned to the more feminised activities and duties, such as shopping and (unwaged) domestic work, while men continued to dominate the public cultural and political domains, this way reproducing the deep-seated gendered divisions of labour.²⁸

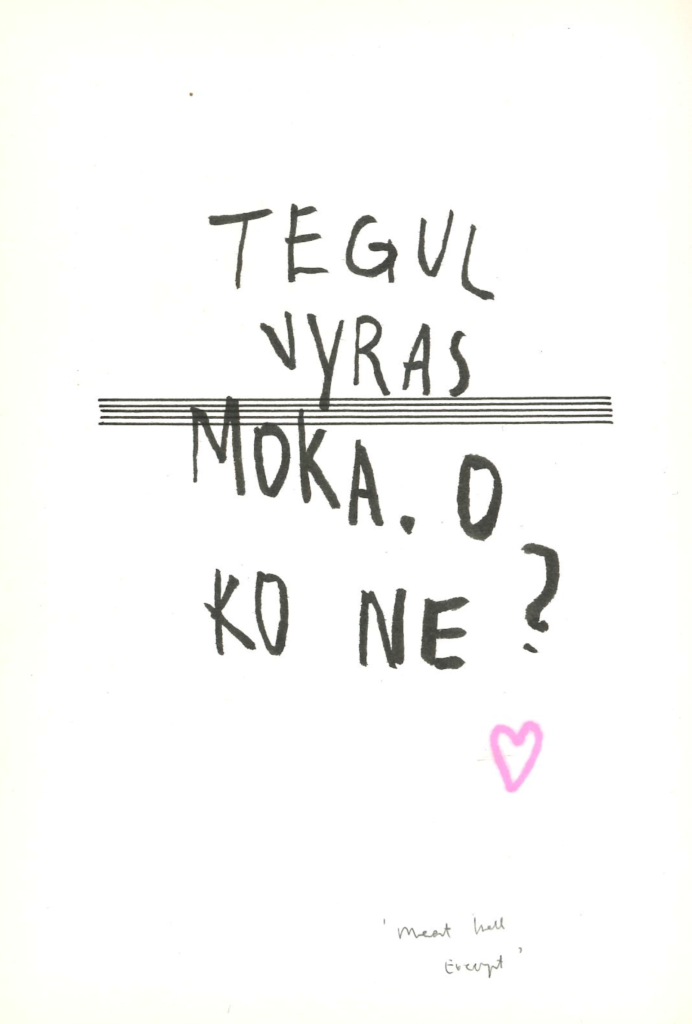

Composition No. 3: Meat Hall, Station Market

Walk around the meat hall

in circles

for 5 minutes.

Listen to the general hum of the trade:

buying, selling, packing.

Stop.

Listen to voice 1: ‘Neeeee, nepirk pas tą seną bobą, jos visi produktai sukrešėję’. [Noooo, do not buy produce from that old woman, it is all gone off]

Turn around.

Listen to voice 2: ‘Kur ta prostitutka pardavėja? Turbūt užmigo tūlyke.’ [Where’s that prostitute saleswoman, she probably fell asleep on the toilet somewhere]

Continue walking. Eavesdrop further: ‘Ne jūs ką, ką čia moteris ir už vyrą mokės? Tegul vyras moka, dar to betrūko.’ [No no, why should a woman pay for a man? Let the man pay, ridiculous.]

Stop. Listen globally for gender for two minutes.

Note down.

Leave the hall.

Can you hear the traffic?

The gender structures, the way they are projected and experienced within, through and alongside the sonic in contemporary Lithuanian environments, continue to present hybridised tonalities, as the socio-cultural and political attachments to gender lines and binaries, are still seen, felt and heard. These lines can be discovered within the lived spaces of the everyday as well as the governance of Christian-led government and institutional bodies promoting and protecting the notion of ‘family’ as a heterosexual institution through ‘family strengthening’ laws and policies. The everyday life, as the initial recordings and notes reveal, is suffused with normative hierarchies and exclusions, sexist jokes, misogynist tones, casualised racism, homophobia and transphobia. Listening for gender reveals that society continues to organise itself predominantly within the bounds of the two-gender binary (female/ male, masculine/feminine) and patriarchy-led gender hierarchies. Tuning into the everyday, you quickly discover how the voices and lives of single mothers, carers, victims of domestic abuse, LGBTQI+ and Trans people continue to be diminished, ignored, excluded and invisibilised.

The broader geopolitical context of the neighbouring ‘Post-Soviet’ states further contributes towards the country’s already knotted socio-political soundscapes. When extending the ear and listening out for gender in Poland, Belarus, Ukraine and Russia, for example, one quickly begins to discover a spectrum of dark resonances: attempts to control and re-nationalise women’s bodies, far-right nationalist groups’ acts against women’s reproductive rights, a rapid increase in gender-based violence and domestic abuse, the silencing of LGBTQI+ and Trans communities, exclusions of racialised bodies, including migrants and refugees, and their retainment at the border, as well as the weaponisation of women’s bodies in Russia’s war against Ukraine. Listening for gender, in the contemporary moment of ‘now’ within the ‘Post-Soviet’ bloc, is, indeed, a heavy task.

As I continue to listen for gender, however, I also discover the sounds of agency and resistance, reverberating against toxic masculinities and institutional walls and structures. These are the audible resonances of feminist acts, activist organising, ‘safer’ sounding spaces created for women, LGBTQI+ and non-binary communities to do collective work, archives and art initiatives, echoing and growing with time. While located within the margins and the edges, while communicated and shared, at times, with and through silence, the soundscapes of resistance and agency are present, and that matters. They matter because they are able to educate, offer new imaginaries and project alternative social and political realities, based on collective power. The task, thus, is to keep listening, listening deeply and openly, with the hope and confidence that by listening, noting and sharing, gender roles, lines and binaries can be obscured and eventually eradicated.

To do that, I continue to listen out to homes, workplaces – from markets, offices to beauty salons, I tune into social and political places (both physical and virtual) and explore the uncomfortable socio-economic hierarchies and exclusions further. I record ‘mothers’ kitchens’, including their silences and unpaid labour, I listen to the ‘feminised’ duties and jobs within the current liberalised economy and note down feminist voices and echoes. While I listen, I turn the uncomfortable tones, discovered within the everyday, into soundscape compositions as a way of offering collective forms of processing how gender, in our lived spaces, might be sounded, and sound is gendered.

Sandra Kazlauskaitė is an artist and researcher working across the disciplines of sound installation, sound performance and theory-led projects in auditory culture. With her works, Sandra explores the concepts of silence/silencing, gendered soundscapes as well as the production of political and embodied sonic space. Her practice is embedded in feminist writing and practice, including the works of Pauline Oliveros, Ursula Le Guin and Sara Ahmed. Sandra is a Lecturer in Sound and Music Theory at the University of Lincoln, where she researches and teaches theory and practice of soundscapes, practices of listening, audiovisual arts practice, sound and music cultures. In 2019, Sandra was awarded a PhD at Goldsmiths College for her practice-based project ‘Expanded Aurality: Doing Sonic Feminism in the White Cube’. Her publications include ‘Soundscapes of the Post-Soviet World Today’ in Leonardo Music Journal (2015), ‘Doing Sonic Feminism’ in Atlas of Diagrammatic Imagination (2019) and ‘Women Sonic Thinkers. The Histories of Seeing, Touching and Embodying Sound’ in The Bloomsbury Handbook of Sound Art (2020). Sandra also makes ambient music and is a part of the female and non-binary DJ collectives SISU and GUYZ.

1

R. Murray Schafer, The Soundscape: The Tuning of the World, Rochester, VT: Destiny Books, 1993.

2

Paul Rodaway, Sensuous Geographies: Body, Sense, and Place, London: Routledge, 2011, p.86.

3

Jonathan Sterne, ‘Soundscape, Landscape, Escape’, Soundscapes of the Urban Past: Staged Sound as Mediated Cultural Heritage, ed. Karin Bijsterveld, Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2013, p.182.

4

Christine Ehrick, Radio and the Gendered Soundscape: Women and Broadcasting in Argentina and Uruguay, 1930–1950, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

5

Christine Ehrick, ‘Vocal Gender and the Gendered Soundscape: At the Intersection of Gender Studies and Sound Studies’, Sounding Out, 2 February 2015, https://soundstudiesblog.com/2015/02/02/vocalgender-and-the-gendered-soundscape-at-theintersection-of-gender-studies-and-soundstudies/ accessed 14 July 2022.

6

The idea of ‘lived space’ is explored in Henri Lefebvre’s work. In The Urban Revolution, Henri Lefebvre writes: ‘Space is only a medium, environment and means, an instrument and intermediary […] [It] never possesses existence in itself but always refers to something else, to existential and simultaneously essential time, subjective and objective […]. For more, refer to: Henri Lefebvre, The Urban Revolution, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003, p.73

7

For more, refer to: Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, Oxford: Blackwell, 1991 and Doreen Massey, For Space, Los Angeles: Sage, 2005.

8

Pauline Oliveros, Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice, New York: Universe, 2005.

9

Helmi Järviluoma, Anni Vilkko, and Pirkko Moisala, Gender and Qualitative Methods, London, Thousand Oaks, California: Sage, 2003, p.104.

10

Jean Fran.ois Augoyard et al., Sonic Experience: A Guide to Everyday Sounds, Quebec: Mcgill-Queen’s University Press, 2011, p.123.

11

Anne Carson, Glass, Irony, and God, New York: New Directions, 1995, p.121.

12

Carson, Glass, Irony and God, p.126.

13

Carson, Glass, Irony and God, p.119.

14

Carson, Glass, Irony and God, p.126.

15

Carson, Glass, Irony and God, p.127.

16

Anne Karpf, The Human Voice: The Story of a Remarkable Talent, London: Bloomsbury, 2007, p.160.

17

Marie Thompson, ‘Gossips, Sirens, Hi-Fi Wives: Feminising the Threat of Noise’, Resonances: Noise and Contemporary Music, New York and London: Continuum International, 2013, p.299.

18

For more, see: Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, London: Routledge, 1990.

19

Marie Thompson, ‘Gendered Sound’, The Routledge Companion to Sound Studies, ed. Michael Bull, Abingdon: Routledge, 2018,

p.108.

20

Thompson, ‘Gendered Sound’, p.108.

21

Thompson, ‘Gendered Sound’, p.109.

22

Barry Blesser and Linda-Ruth Salter, ‘The Other Half of the Soundscape: Aural Architecture’, World Federation Acoustic Ecology Conference, 2009.

23

Sarah Ashwin, ‘A Woman is Everything: The Reproduction of Soviet Ideals of Womanhood in Post-Communist Russia’, in Al Rainnie, Adrian Smith, Adam Swain (eds), Work, Employment and Transition. Restructuring Livelihoods in Postcommunism, London, Routledge, 2002, p.119.

24

Olga Voronina, ‘Soviet Patriarchy: Past and Present’, Hypatia 8, no. 4, November 1993, p.10.

25

Herwig Reiter, ‘“In My Opinion, Work Would Be in First Place and Family in Second”: Young Women’s Imagined Gender–Work Relations in Post-Soviet Lithuania’, Journal of Baltic Studies, Volume 41, no. 4, December 2010, p.532.

26

For more on this topic, read: Éva Fodor, ‘Gender and the Experience of Poverty in Eastern Europe and Russia after 1989’ in Communist and Post-Communist Studies, Volume 35, no. 4, 1 December 1997, pp. 369–82.

27

Viktorija Kolbešnikova, ‘Post-Feminismin Post-Socialist Lithuania: Soviet Woman Becomes Woman’, 2019, p.60.

28

Jolanta Reingardienė, ‘Lyčių Politika Lietuvoje. Smurto Prieš Moteris Šeimoje Atvejis’, Sociologija. Mintis Ir Veiksmas 9, no. 1, 10 July 2002, pp.16–33.