The Contours of Paranormal Music in Lithuania

The contemporary music festival Sumirimas (Die In), later known as Didelis pasaulis! (Big World), launched 25 years ago, and the opera-performance Sun & Sea that was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in 2019, are not directly connected, but demonstrate how Lithuanian sound art is interrelated and taking on new forms. In her youth, Lina Lapelytė, the composer of Sun & Sea, drew inspiration from experimental music performances in Kaunas, and her colleague, writer Vaiva Grainytė and the opera’s librettist, once belonged to the avant-garde group Sugyvulinos Latakams and participated in the Sumirimas festivals. Ramūnas Jaras organised the first revolutionary festival event in Kaunas in 1996. Digitised videos of Sumirimas, consisting of over 60 hours of paranormal sounds and images, were recently published on the internet.

Speaking about Sun & Sea, contemporary culture researcher Jurijus Dobriakovas draws attention to one particular trajectory in contemporary Lithuanian sound art: ‘I would say that the work itself is a triumph for all Lithuanian art, because the sound within it is not somehow exclusively thematised, the significant accents are focused entirely elsewhere. In my view, this reflects the overall situation of current Lithuanian sound art: the best and most interesting works in which sound is an important concept element are those which do not distinguish themselves namely as works of sound art, since that would inevitably confine them within a genre “ghetto” of sorts, and that simply is no longer effective and becomes formalistically limiting. For this same reason, any kind of national sound art “school”, whose contours may still have been tangible in prior decades, can hardly be said to exist today – the most relevant Lithuanian sound artists have simply dispersed throughout the entire field of contemporary art and the world, while others have probably abandoned this activity or simply limited themselves to creating music.’

The vanishing boundaries between different artistic disciplines drives the search for new terminology with which we might encode the media arts that involve creative activities and various sound experiments that no longer fit (or don’t even try to fit) within the definition of ‘music’. Initially, such experiments were called ‘exploratory music’ or ‘sound sculpture’, but the concept of ‘sound art’ took hold around 1980. It’s often debated whether sound art belongs to the field of the visual arts or experimental music, or to both, but within it we can find the traces of many other movements: conceptual art, minimalism, site-specific art, sound poetry, electroacoustic music, avant-garde poetry, sound design, etc. Before they were even identified as such, works of sound art were created by the Dadaists, Surrealists, Situationists, Fluxus artists, and others. The organisers of the Skaņu Mežs festival in Latvia describe its content as ‘adventurous music’. Because the concept of sound art is a bit fuzzy, in this article, I’ll try to sketch out the contours of adventurous music in Lithuania from about the 1990s to the present.

Art historian, curator, and interdisciplinary artist Tautvydas Bajarkevičius, when asked at what point experimental, improvisational, contemporary and other similar music becomes sound art, replied that: ‘Music, in and of itself, does not, apparently, become any other form of art. At the same time, sound art is constantly defined as existing between contemporary music, media art, and the visual arts. In this respect, it often seems to lack autonomy. Simply put, you won’t hear sound art at a concert – unless we use this concept as a poetic description of music, as a metaphor. Most often, sound art is exhibited, and sometimes it’s broadcast. Stage performance is also possible within the limits of sound art, but here the distinction is sometimes difficult to discern and justifiably raises questions like this one, to which it’s not always easy to provide a straightforward answer. Sometimes, especially here in Lithuania, it’s also a question of identity – given the creative methods they use, experimental music artists tend to call themselves sound artists, even though many of their stage performances don’t really go much beyond usual concert conventions.’

Jurijus Dobriakovas feels that music simply meant for listening can hardly be considered sound art, no matter how ‘non-standard’ its form may be: ‘In order to be able talk about sound art, the sound phenomenon itself, as well as its various psychoacoustic, cultural, social, political, and other contexts have to be activated and conceptually reflected, in one way or another, within a particular work. This means that it must encourage reflection on the part of the listener/viewer, and not, on the contrary, some immersion into a kind of hypnotic state.’ For this reason, Dobriakovas believes that it is difficult to say which field is closest to sound art – music or contemporary visual art, although he does prefer the latter: ‘An in-depth exploration of sound phenomena requires not so much a concert space, but an exhibition space, capable of accommodating installations that combine several means of expression and involving the listener/viewer. The creation of sound art also often requires a connection, of one or another type, between sound and imagery, which then meaningfully expands the field of sound experience and comprehension. To be sure, this can also take the form of an audio-visual demonstration or performance, but in this case, there is often a risk of elementary illustration. If there is no conceptual link between sound and image, it’s likely that the moving image is simply accompanying the sound to make it easier to listen to certain sounds that are not very easy to assimilate, or are just rather monotonous – but sound art is not born of that.’

Before the late 1980s, sound art had very few chances to gain ground in Lithuania – formalism and abstractionism were deemed undesirable in Soviet art and everything was overseen by censorship agencies. The Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 led to new restrictions and ideological requirements, and the regime’s control tightened even further in Lithuania in 1972, after the self-immolation of Romas Kalanta, who had left behind a message in his notebook: ‘Only the system is to blame for my death.’ The Baltic republics in the western part of the Soviet Union were known as ‘the near abroad’, thus it is not surprising that it was precisely here that some westerly winds penetrating through the Iron Curtain were most keenly felt. One such manifestation was the contemporary musical festival Warszawska Jesień (Warsaw Autumn), held in neighbouring Poland since 1956.

The Singing Revolution began in Lithuania in 1988, led by folk and patriotic songs, but rock music was also given its 15 minutes of fame. Once the romantic euphoria subsided, airwaves were taken over by cheap and easily consumable pop music. Polish composer and multi-instrumentalist Mieczysław Litwiński, who has lived in Lithuania, observed: ‘Music always describes the state of society. As goes society, so goes its music. The music that children listen to tells us what the society will be like in the future.’

According to Dobriakovas, the origins of Lithuanian sound art are rooted in various performative practices that emerged on the arts scene in the 1980s and 1990s, such as the Anykščiai happening festivals of 1988 and 1989, organised by contemporary music composers (including Gintaras Sodeika, Šarūnas Nakas, Rytis Mažulis, and Ričardas Kabelis) together with artists from other fields. These events offered a space to hear experimental music and free, live artistic creativity in general that could not be so openly performed elsewhere (in the biggest Lithuanian towns, for example). Other examples were the Sumirimas (from 1996 to 1999) and Didelis pasaulis! (from 2000 to 2014) avant-garde music festivals organised in Kaunas by Ramūnas Jaras. Culture researcher Dobriakovas believes that it was likely this format of happenings / performances / live art / free improvisation that determined that the field of experimental sound art in the first decade of the twenty-first century was based primarily on live performances, and not on the ‘more sculptural’ or installation forms more closely associated with contemporary art.

One of the first events featuring ‘adventurous’ sounds was the Jauna muzika (Young Music) festival, presenting artists working with sound and music as an experimental form of art. Composer Antanas Jasenka remembers the unexpected financial support he received. A stranger presented the emerging composer with 3,000 dollars – the price of a one-bedroom flat in Vilnius at that time. Jasenka transferred the money to the account of the Lithuanian Composers’ Union and in 1992, together with Remigijus Merkelis, Kipras Mašanauskas, Egidijus Čirvinskas, and Darius Butkus, began the story of one of the oldest musical festivals in Lithuania. As Jasenka notes, he and his colleagues were interested in technology, experimental music, and what lies beyond music.

Organisers sought to present contemporary classical music and academic electro-acoustic works. As musical concepts changed, so did the festival itself. Today, Jauna muzika presents an especially broad spectrum of music, often transcending the boundary where sound is no longer a requisite condition for music and exploring musical genotypes and stimulating the sensitivity of audiences’ vestibular, inner ear.

In recent years, Jasenka has been creating intensive, dynamic, and multifaceted music, whose texture is enriched by all sorts of sound objects (harsh noise, glitches, soundscapes, etc.). Since 2008, he has been a member of the experimental project DIISSCC Orchestra, along with Martynas Bialobžeskis, Jonas Jurkūnas, Vytautas V. Jurgutis, and Arūnas Zujus.

The band NAJ released its debut album Fixthemeteronthezeroposition in 1994. In the early years of his creative work, architect Darius Čiuta and his colleagues Algis Mielius and Rolandas Cikanavičius became interested in unconventional and experimental types of music, industrial music tracks, and the aesthetics of noise. Later, the US record label RRRecords included NAJ’s album Restitution Smile, together with such stars of experimental music as Merzbow, Aube, Thurston Moore, and others, in its Pure series – establishing a new territory on the map of international experimental music.

Several years later, in 1997, the Musica Ficta Contemporary Music Forum was held in Vilnius, including the presentation of work by Philip Glass and the documentary film Four American Composers by Peter Greenaway (about Glass, Robert Ashley, John Cage, and Meredith Monk), and featuring participating performers such as the Kronos Quartet and Piano Circus (an ensemble of six pianists), and the presentation of works by Lithuanian composers such as Rytis Mažulis, Vytautas V. Jurgutis, and others.

The transition from a planned economy to the free market produced something akin to an esoteric ether in which UFOs and other paranormal phenomena also found their own audiences. In their attempt to come to terms with a changing reality, people began searching for salvation in parallel worlds. One of the most popular publications on this subject, the weekly Žvilgsnis (Sight), published in Lithuanian and Russian, saw its circulation expand by more than 35 times, surpassing 175,000 by 1993.

Within this context, the contemporary art promoter, curator, composer, writer, and poet Ramūnas Jaras, also known under his artistic pseudonym Echidna Aukštyn, combined satire and humour in his ‘paranormal’ creations with atonal sound experiments and melodies, compelling listeners to arrive at a state of the ‘here and now’. Jaras became known for his face-covering mask and characteristic shirt. Around 1997, he created and performed his work in his own style called kaholizmas. Often unjustly criticised, this pioneer of Lithuanian performance and musique concrète has regularly toured the world with his performances: persecuted by the local police in China, nearly trampled by elephants during a performance in Ghana, losing his personal documents in New Guinea, and appearing in such countries as India, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Bermuda, and elsewhere.

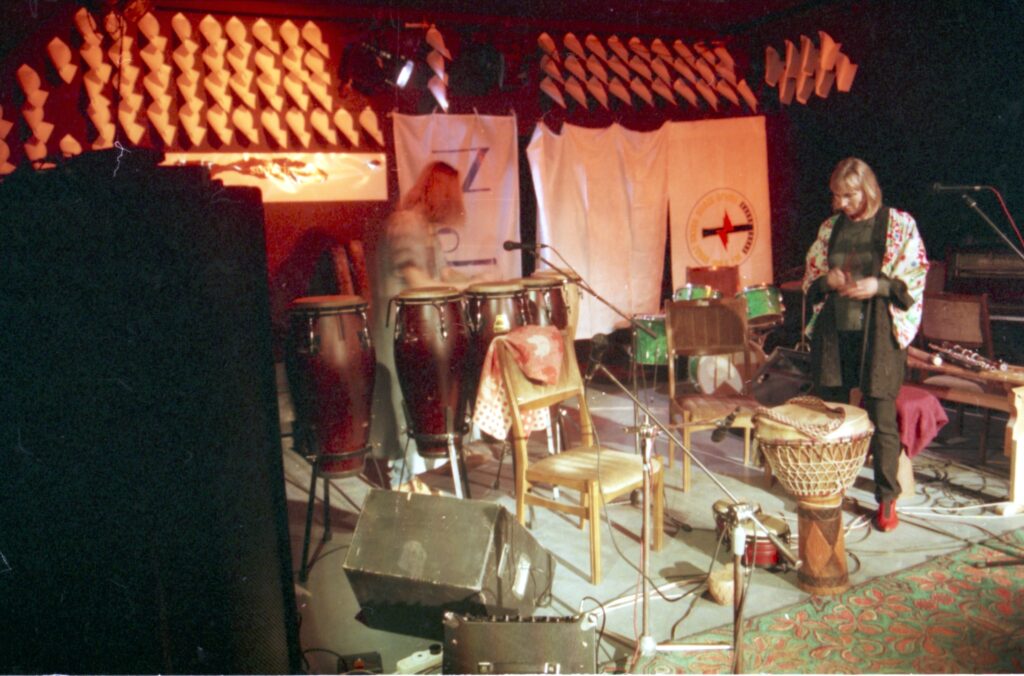

In 1996, Jaras came up with the idea to start a paranormal music festival called Sumirimas in Kaunas. Speaking with journalists during the festival, Jaras said: ‘I want people to listen to music that is not just enclosed in a shell of human understanding. Let’s say I want to eat, I want to sleep, I want this or that. This is music that says, maybe I want to go out of my mind, or I want to go into my mind. Avant-garde music and its exploration are only accessible through nonexistence. One abstract line of measurement passes into another abstract line at the zero point. Other dimensions can only be reached through zero, only through death. Death is the chance to end up somewhere else, which is why “sumirimas” is the best name for a paranormal music festival.’

‘Paranormal music was defined as such because it was “paranormal” to society at the time, because society didn’t know what contemporary music was and anything contemporary was seen as abnormal,’ Jaras remarked recently. ‘“Paranormality” is a gentler way of describing the contemporary, acknowledging that, OK, I know this music is abnormal for you, but look: maybe it’s actually PARAnormal, and not just abnormal? Our society is a post-Soviet one, after all, and it considers abnormal something that is normal in the normal world. And I don’t associate “paranormal” with the paranormality of unidentified flying objects. There was just no more room to dig around for the right term.’

As the festival’s mastermind, Ramūnas Jaras actually understood ‘contemporary’ to be ‘post-post-modern’ music, so the festival’s innovative nature caused a stir in the media, and some of the bands that played in the festival were even ridiculed afterwards. Acts were performed on stage that contrasted sharply with the Soviet understanding of music. The festival featured most of the contemporary Lithuanian bands or performers of the time, a dozen or so every day, and even as concerts ended, usually in the early hours of dawn, audiences were reluctant to go home.

Jaras funded most of the festival out of his own pocket, driven by the idealistic goal of providing a stage for contemporary Lithuanian music. ‘In 1996, the most popular band in Lithuania was Dinamika. It’s a great band and the public really loves them. When I went looking for sponsors for Sumirimas, one said to me: “Oh. These are all unknown bands”,’ Jaras recalls. ‘I had some knowledge of what was going on in the world, but that was not the internet era. For example, composer Giedrius Kuprevičius, a friend of the festival and a strong critic, gave me a catalogue of festivals taking place in Europe at the time.’

Sumirimas attracted all sorts of performers of ‘strange’ music. The festival featured the aforementioned NAJ, Donis, Gintas Kraptavičius, N. N. N., Mieczysław Litwiński, Gailė Griciūtė, Marius Salynas, GYS, Betoniniai triušiai, Žuwys, Tautvydas Bajarkevičius, Benas Šarka, Šalikąpalikau, A. Jasenka, Empti, Sosudduara, 7b Orchestra, Drigentai, Ženklo grupė, Nils Ille, Girnų giesmės, Arturas Bumšteinas, Gintas Gascevičius, and others. Also, the prominent band Ir visa tai, kas yra gražu, yra gražu, whose early recordings are scheduled to be released by the British label Strut Records. The band leader Baras was a known collector of books and records and the joke goes that he owned some Merzbow releases that even Masami Akita didn’t know about. Baras was also active in experimental filming. Zona Records is about to release the double vinyl Baras soundtracks – various adventurous sound artists contributed their pieces inspired by his movies.

Sumirimas was held regularly up until 2003, and then resumed after a break under the title Didelis pasaulis. ‘After several festivals I just continued the phase, I didn’t end it, because life is in death, and death is everywhere, just like its opposite, which is not completely opposite, because life exists always, and is an opposite only upon death. The current state of Sumirimas will be revealed in due course; now it’s in the form of a surprise,’ said Jaras, leaving us wondering.

At the start of the new century, the greatest focus was directed at the established fact of ‘non-format’ sound creation and live performances, mostly using portable computers and visualisations that were meant to raise the already fairly static action (regardless of the activity of the sounds themselves) to the level of sound art. In Dobriakovas’ view, those creating more conceptual work, using different tools, included Andrius Rugys (PB8) and Arturas Bumšteinas and his laptop quartet called Twentytwentyone, which in addition to Bumšteinas include Lina Lapelytė, mentioned at the start of this article, as well as Antanas Dombrovskij and Vilius Šiaulys.

Rugys developed multifaceted, usually collective projects (which we might call artistic exploration today) that reflected the significance of sound in our lives and surroundings, as well as the motley scene of sound creators itself and its identity (e.g.,Rugys’ 2006 thesis project PB8_001_+V). Bumšteinas was one of the first composers and experimental electronic music artists who felt equally at home in contemporary art galleries and concert spaces. In works that approximated conceptual art, sound was in one way or another important, but it was not necessarily the most significant element in the piece. In its performances, the Twentytwentyone quartet use images conceptually – not simply as a distraction for the eyes, but also as a means to demonstrate graphic scores (guidelines for performing works written by means of unconventional music notation systems that lack the fixed meanings usually found in conventional sheet music) created by various contemporary music composers, which the quartet would then interpret in real time.

One of the most prominent sound artists of the past decade is experimental music creator and performer Armantas Gečiauskas, better known as Arma Agharta, who was particularly active on the alternative cultural scene in Lithuania and abroad for two decades, staging over 500 performances in different parts of the world, from Greenland to Indonesia, from Siberia to Brazil. According to art critic Alberta Vengrytė, ‘in his performances, Arma doesn’t limit himself to “sound in itself”: the performer’s unexpected movements that transcend traditional systems of emphasising, and his improvised games, DIY “cheap magic tracks”, and the new, non-existent “languages” that Gečiauskas discovers during his performances, all convey the artist’s principled anti-referentiality.’

Several years ago, exhausted from his constant touring, Gečiauskas began working with sound cassettes and created an e-commerce site called Tapekiosk.com. He also participates in different flea markets. Sharing his memories in an interview about the start of his creative career, Arma Agharta recalled: ‘I managed to catch the start of the 2000s, when computer music began to blossom. What I remember most are the events, because that direct, live experience was the biggest hook. Festivals like Garso zona (Sound Zone), Jauna muzika with Merzbow, Baltas triukšmas (White Noise) in Birštonas, E-xpansija in Kaunas, the Virpesys club in Vilnius, as well as the Homo Ludens festival, with all its strange music and art, in my hometown of Jonava.’ Adventurous sounds could also be found at the Centras media art festival in Kaunas, or at Enter in Šiauliai, as well as other music and media art events.

Ten years later, Gečiauskas himself and his label Agharta invited visitors to educate themselves, listen, and seek out new experiences at the Speigas (Frost) Festival, and in 2018 he curated Garso Teatras (Sound Theatre), an international event that brought together sound art and theatrical spaces in Panevėžys. The programme included the technical theatre of Erika Alalooga, a ritualistic performance by Benas Šarka, the multilayered compositions of Waterflower, ID M Theft Able, and Opera Maleta, as well as Dadaist pranks by Arma Agharta himself. The sound art examples included objects and instruments by Simonas Nekrošius, a sound sculpture by Antanas Dombrovskij, and a multisensory installation by Tadas Stalyga.

‘Most of the work then called sound art was more within the realm of experimental music, but that shouldn’t diminish its value. One interesting detail is that a large group within this community were architects by training and by profession, which probably led to the “architectural” nature of their sound creations, and the digital conversion of sound data into image structures and vice versa, particularly in the case of Tomas Grunskis (ad_OS),’ said researcher Dobriakovas, acknowledging that ‘there were far fewer interactive installations and other similar spatial forms, although sound was sometimes used in different interdisciplinary new media projects, where it was combined with various visual forms and presented as site-specific installations in galleries or alternative exhibition spaces, such as Lina Miklaševičiūtė’s work Prospektas (Prospect) in 2006, in which sound from Gedimino Prospektas was broadcast live into the gallery, and a section of the building’s façade was displayed on the inside, using photographic means.’

A new generation emerged after 2010, drawing inspiration from somewhat different fields, such as the students at the Sculpture & Photography and Media Arts Departments at the Vilnius Academy of Arts, who used sound according to the principles of conceptual, contemporary (visual) art. Perhaps they were influenced by an exhibition entitled ‘Pionier’, mounted at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius in 2011 by German artist Carsten Nicolai (known in the music world as Alva Noto), in which sound was inserted using sculptural means and kinetic (moving) installations. Dobriakovas believes that the second decade of the new millennium saw the increasing emergence of certain ritualistic, mental, and meditative sound qualities, including by the aforementioned Andrius Rugys and his creation of inclusive installations meant for the deep listening of environmental recordings and other sounds (his Garso korys project) and his promotion of group exercises devoted to honing one’s garsuotė – a new Lithuanian term akin to ‘sound-ination’, combining the Lithuanian word garsas (sound) with vaizduotė (imagination). Audrius Šimkūnas, best known for his heavy metal and postindustrial music band Sala, also rose to increasing prominence as a sound artist, applying a conceptual but also ritualistic approach to field recordings, radio waves, contact microphones, electromagnetic resonance meters, and similar technologies used to ‘make the inaudible audible’. Arturas Bumšteinas’ latest projects combine sound art and theatre, and the exhibition ‘Stereoscopus’, held in Vilnius in the spring of 2022, was mainly devoted to forms of sound art and consisted nearly entirely of sculptural and installation forms that variously reflected the relationship between sound and the surrounding environment.

Speaking about the sound art scene in Lithuania, experimental electronic music creator Gintas Kraptavičius (known by his pseudonym Gintas K) noted that, given the size of Lithuania’s population and the percentage of creative people there, Lithuania surpasses most of the world’s big cities. Of the nearly 4 million people who lived in Lithuania in 1990, slightly less than 3 million remain, but one can still encounter the full range of frequencies heard around the world. In his effort to present a broader overview of local creators, Kraptavičius released an album in 2012 entitled Lietuvos garso menas (Lithuanian Sound Art), featuring objects created by A. Rugys, Antanas Dombrovskij, audio_z, V. V. Jurgutis, L. Lapelytė, A. Bumšteinas, Gintas K, ad_OS, A. Jasenka, and SALA. ‘This stylish collection gives the impression of a tried-and-true album. The tracks, from various subgenres of experimental music, work well together, with an electroacoustic piece accompanying a cut of ambient sounds, a collage composition picking up from a glitch atmospheric work, and a computer electronic etude complementing an ambient creation. There are no works that fall out of or stand apart from the context; the album has a good vibe to it.’ So ran the review of the album by Robertas Kundrotas, the writer and former editor-in-chief of the influential new music magazine Tango, adding that ‘if this work aspires to be comprehensive, then it has its gaps, but if it is only the first window into the large and colourful contemporary music world in Lithuania, then, even having missed such pioneers as Darius Čiuta, Raimundas Eimontas, Orlandas Narušis, or Atrac, I believe that a place will be found for them in this work’s next monumental volume.’

In 2019, the Music Information Centre Lithuania (MICL) released a promotional sampler entitled Note Lithuania Experimental/Electronic, which did not include any of the pioneers mentioned above, but which did showcase sounds from recent years created by: Patris Židelevičius, Skeldos, Daina Dieva, Distorted Noise Architect, NULIS:S:S:S, Tiese, Unit 7, Fume, Nortas, avidja/devita, and others. One of the compilers of the album, Jurijus Dobriakovas, with whom we spoke for this article, presented it thus: ‘This new Note selection clearly demonstrates two things. First: the familiar mainstays of the Lithuanian postindustrial, noise, drone, and dark ambient electronic music scene is still very active and in great shape – which means vital continuity. Second: their trademark sound is being chased closely by rising local and Lithuaniabased international talent that also offers a welcome stylistic expansion – which means healthy evolution. Together, these facts ensure that the small but rich Lithuanian adventurous music universe remains as exciting as ever, and definitely worthy of global attention.’

Indeed, the sound art scene and its related reverberations reflect processes that began 30 years ago and are today a fullyfledged part of the global soundscape.

Around the year 2000, composers Mindaugas Urbaitis and Šarūnas Nakas began speaking about new music on Lithuanian public radio, and since then have produced over 500 episodes of the radio show Modus. To this day, every week the duo explore an array of new music angles, including: ‘Music styles that didn’t become movements’, ‘Is the avant-garde still out in front?’, ‘The splendour and poverty of hedonism’, ‘The electro-acoustic face of Iran’, ‘Gone with symphonism’, ‘Mickey Mouse the Modernist’, ‘Self-isolation and creativity’, ‘What Gen Z girls look for in music’, ‘Girls just want to make noise’, etc. The show was also accompanied by the launch of a new music e-magazine at modus-radio.com, which published texts by music professionals on contemporary music of different styles. Unfortunately, the project has been neglected of late and has not been updated with new text contributions.

The internet radio project Rasų radijas (rasuradijas.lt) began broadcasting in the spring of 2021, presenting shows led by sound artists, philosophers, writers, and curators of artistic and social projects who explore various manifestations of sound art from different perspectives. Rasų radijas is a sound art platform that initiates creative processes and listening sessions. It is a radio gallery devoted to experiments and undiscovered sound experiences, as well as personal audio journeys. The project’s goal is to study sound art manifestations, bring together the artistic community in Lithuania and on the internet, and promote the study, creation, and dissemination of various forms of sound art. The project is curated by sound artist and improviser Gailė Griciūtė, who also took part in one of the already legendary Jaras’ festivals.

Arturas Bumšteinas, one of today’s most prominent sound artists and also a former participant in Sumirimas/Didelis pasaulis festivals, recalls those days thus: ‘Word reached Vilnius about the plans for Sumirimas in 2000. At the time, I’d taken a break from music and had immersed myself in Old Town bar-hopping. So, my friend says to me: Sumirimas is coming, let’s do a project! Inspired by his enthusiasm, I began writing a piece that I planned to submit to Jaras, the organiser of Sumirimas; I wrote and wrote for so long that I missed the actual festival. But I finished the piece – it’s called Storulių Muzika (Fatso Music) – but unfortunately, I can’t remember why – maybe it had something to do with jazz…’ Bumšteinas taught in the UK and Germany, and today speaks about sound expression at the Vilnius Academy of Arts. He has held solo and group exhibitions and taken part in festivals in Europe and the US. Bumšteinas’ work has been released by labels in Lithuania and abroad. He is a recipient of the Palma Ars Acustica prize from the European Broadcasting Union and was awarded the Boris Dauguvietis Earring for his integration of sound experiments within new theatrical forms. For the past few years, Bumšteinas has been curating the Jauna muzika festival programme.

In Vilnius, paranormal sounds can be heard in places like the Studium P gallery, where interdisciplinary artist Simonas Nekrošius presents his objects and sculptures, and whose work is characterised by the DIY and ready-made principles, devoting considerable attention to process, intuition, experimentation, and improvisation. DIY principles are also quite familiar to Paulius Burakas, curator of the Kirtimai Cultural Center, who organised the sound art and experimental events series titled ‘Susikirtimai’ (Intersections), among other projects. The artistic director of the Empty Brain Resort space, Matas Aerobica, in addition to events held in Vilnius, curates the Braille Satellite music and arts festival together with Oscar Olias Castellanos of the Octatanz duo. In Kaunas, the field of experimental sound is being expanded by promoters from the Ghia label. It’s no surprise that in the era of globalism, some foreign artists like French Phil Von (ex – Von Magnet), US performer Zan Hoffman or Italian sound researcher Demetrio Castellucci found their home in Lithuania.

In 2021, the Artūras Areima theatre mounted the experimental art festival technē, whose main idea and goal was to introduce completely different forms and genres of music creation and performance, to broaden the perspective of music and its perception, and to introduce listeners and viewers to the possibilities of expression in contemporary music and the techniques and specific considerations of alternative/experimental music creation and performance.

Art critic Tautvydas Bajarkevičius doesn’t perceive any special national aspects, with the possible exception of the rather ephemeral and fragmented nature of the sound art scene arising from various specific local circumstances. He acknowledges that it is quite difficult to speak in any general way about Lithuanian sound art and he hesitates to draw up any summation: ‘I suppose we have to admit that, over the last 30 years, the epithets “sporadic” and “intense” have become more expressive than “fragmentary” and “individual”.’

Domininkas Kunčinas is a journalism graduate of Vilnius University, an independent researcher of alternative music, editor of the (sub)cultural web magazine Ore.lt, radio host of Radio Vilnius and an environmentally friendly music selector going by the name of ‘Direktorius’. He previously published the zines Decibelai and Kablys sung in the ska/punk band dr.Green; ran the illegal underground venue GreenClub; organised the DIY open air jam, Darom, in the beginning of 2000s; and promoted bands like NoMeansNo, Handsome Furs, Paprika Korps and was stage manager for various festivals including Generatorius, Satta Outside, STRCamp amongothers. Kunčinas contributes texts to Ore.lt and various Lithuanian cultural publications. His fields of interest cover various aspects of subcultures and alternative music.