The Right not to be Offsetted

OFFSETTED traces the emergence of the valuation of nature. The upcoming book will unpack forms of dispossession that are becoming more and more common through the protection – not only destruction – of natural environments. Tying into current struggles for climate justice worldwide, the publication contests neoliberalism as a saviour of its own ecological contradictions: assigning financial value to nature in order to conserve and rebuild it.

CLIMAVORE was born to explore how to eat as humans change climates: a form of devouring that follows the consequences of anthropogenic landscapes affected by intensive forms of extraction. Different from carnivore, omnivore, locavore, vegetarian, or vegan diets, it is not so much the ingredients that define CLIMAVORE, but rather the infrastructural responses to human-induced climatic events. New seasons of food production and consumption have begun to appear.

Jonas Žukauskas:

Descartes, in his writing on optics, proposed an analogy of a blind man and the stick he uses to sense the space and objects around him. Similarly we use certain optics to understand the environment and natural systems that make our worlds; we use optics to sense space and enable our movements.

Your practice is a great example of one that uses different optics, it crosses and cuts through different ideas to re-assemble them in order to re-constitute new knowledge. How do you see your relationship to nature and the forest?

Daniel Fernández Pascual:

Like the analogy of the stick, we like to use artefacts or items, or sometimes food ingredients to try to sense, to a certain extent, different landscapes, conflicts, or different constructions of space. With our current research in forestry in Sweden we are interested in understanding what a forest is and what it is not. In a way a big part of it is just a timber plantation. What happens when we are surrounded by tree plantations instead of a forest? What are the different metabolic relations we have towards these constructed ecosystems? In our work we are looking at how food and feeding connect these different environments with the forest and sea.

Jurga Daubaraitė:

Like the curious connections of salmon from sea to forest. How are these seemingly unrelated things connected?

Alon Schwabe:

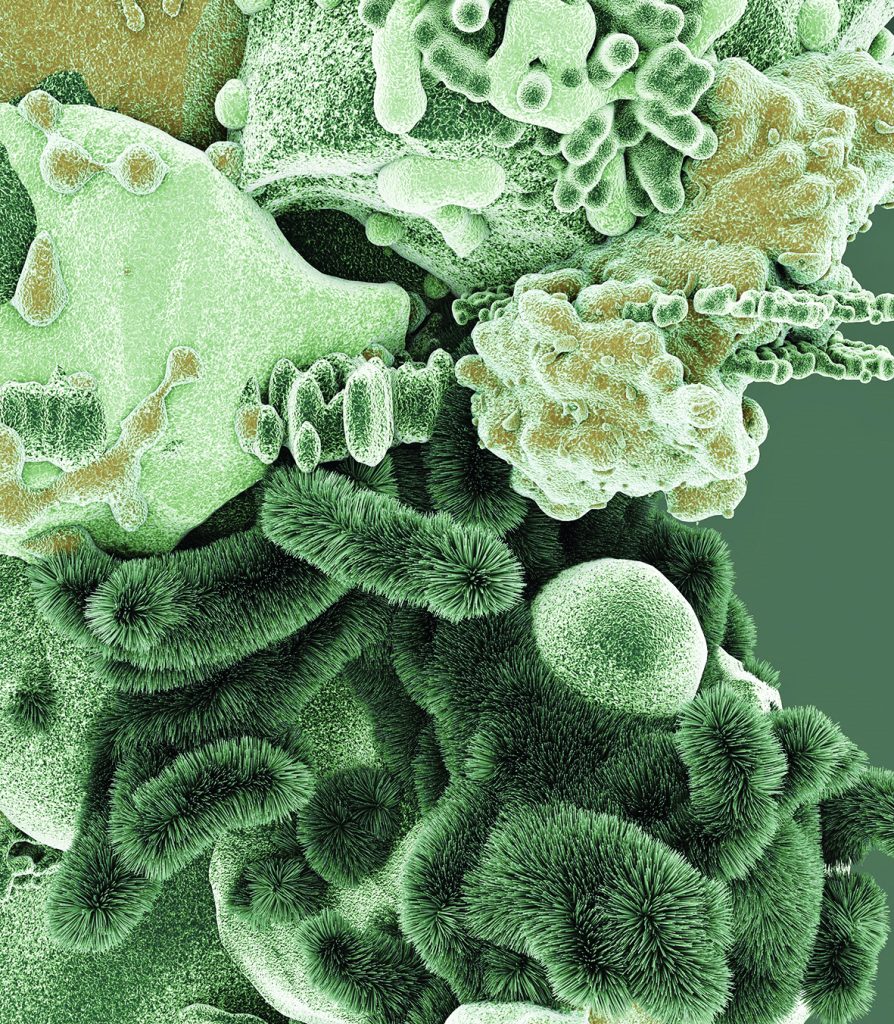

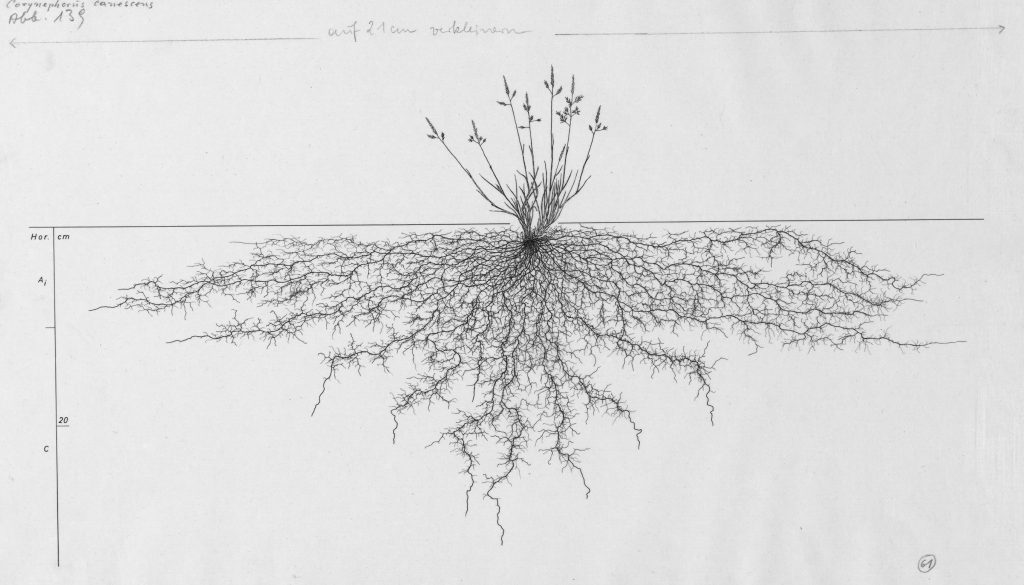

This connection research is in the making. Salmon is a very interesting fish, a creature that works against gravitational forces, and swims against the stream upwards. They have this metabolic system that, after they spawn, they lay eggs and most die. Their carcasses get metabolised by different animals, even by the trees, so they bring marine nutrients like nitrogen from the sea into the forest. And trees that grow along salmon rivers show signs of being much taller, growing much greener. We are doing lots of work to understand these metabolic connections between salmon, sea and trees through the idea of the metabolic forest; thinking about all these species consuming each other, and trees as a key part of the trophic chain.

JŽ:

And the clear-cutting and Swedish model of forestry?

DFP:

The more you clear-cut, the less capacity the soil has to store heavy metals that appear naturally in the soil, like mercury. Apparently most soil has mercury and it’s fine, as long as there are trees with roots retaining it, but when land is deforested, all those minerals start flowing into rivers, severely affecting fish.

AS:

We have been interviewing scientists from Sweden as there is a whole stream of research looking into the environmental effects of clear-cutting and how it has changed the whole landscape of the country; and whether this idea of a ‘forest’ still exists at all. Because most of Sweden now has planted forest, it is more of a plantation.

DFP:

In numbers, some claim less than 10% of Sweden is actually ‘forest’, even though it’s all covered in trees.

AS:

At the moment there are different environmental groups that are monitoring, advocating and working against these timber plantations, so we are really trying to understand what goes beyond the forest itself, and how trees are interconnected. Not only to each other, and how trees communicate, but how trees are part of these metabolic relationships that expand beyond the forest, having ramifications that go deep into the sea (either the Baltic or any other).

JŽ:

So the stick is much longer than it appears. Initially our fascination was that everyone with an interest in the forest wants to extract something; to cut timber, forage, use it for recreation – all these interests are really shortsighted and unaware of each other and most importantly unaware of the autonomy of nature. And you bring these controversies to art institutions and cultural organisations to reveal them. Your CLIMAVORE project led to outcomes such as taking salmon off the menu at the Tate galleries for good. How far do you go with your practice?

DFP:

In general we start with a question that interests us, an event or anecdote. We respond to invitations – sometimes it is self-initiated work, but we try to think about what happens outside the exhibition space, or how to engage with certain practices of the institutions that we work with that we could disrupt and how the work can become an embedded part of their own practices. In the case of Tate, for instance, where we recently did an exhibition, there was an installation where you could listen to atrocious stories about farmed salmon. But more importantly, we used Tate as a platform to change certain food practices. We worked with Tate Eats for 1.5 years to remove farmed salmon from their museum restaurant menus forever. For us, this was the core of the exhibition, and then you would of course go to the exhibition space to see the installation about the construction of salmon as a colour and a fish. But the core action was the act of removing salmon in perpetuity.

JD:

I remember the petition that you’ve been working on as part of your exhibition ‘Offsetted’ in New York, how did that initiation for an amendment of the right of trees continue legally?

DFP:

That project was connected to offsetting mechanisms and how the trees of New York have been used for centuries, in a way, to displace the population from Native Americans, African Americans, and low-income inhabitants in certain neighbourhoods. On the other hand, trees have also been used by people to stay in place. Grassroots movements have been forming throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries for people not to be priced out of their homes. In many cases, this struggle has brought neighbours together as a resistance movement to protect a single tree or a park. We wanted to trace all those different stories, all the way to the present, when there are all these new tree planting schemes. Michael Bloomberg’s 2007–2008 plan to plant 1 million new trees in the city has created a lot of tension. Some of the trees have been used to offset carbon emissions, but even more so in certain neighbourhoods, especially Puerto Rican or Lantinx, where people are seeing trees as a warning sign to be priced out. When new trees arrive, the neighbourhood improves, but it also means that new developments, and new tenants push up the rent. So, in some cases people have even been uprooting newly planted trees, because they see them as a threat. We collaborated with lawyers from CELDF that work with environmental organisations and deal with the rights of nature to think about a new critical framework for the city of New York. They have worked in Ecuador and Bolivia to write the rights of nature into the Constitution, and the more recent Lake Erie case; pushing for it to gain non-human rights recognition. So we worked with CELDF to write an amendment to the City’s code and grant trees the right not to serve as carbon offsets. We used the platform of the exhibition to write that legal draft.

JŽ:

Interestingly, just a couple of days ago we witnessed the cutting of an old chestnut tree in the centre of Nida near the city municipality. It looks like the old tree was taken out to make space for new paving tiles. There are currently a lot of discussions in Lithuania about the rights of nature. And there are proposals to set the value of carbon offsetting to existing green spaces in the cities, which seems to be a symbolic game to encourage conservation when there are no other tools available. What history does this idea hold?

DFP:

Carbon trading is a big market that started with the Kyoto protocol in the 1990s as a way for the Global North to agree to ‘reduce’ emissions, not to pollute less. Instead, a new form of speculative trade was invented to send your pollution quotas to countries in the Global South, who are suddenly trapped in a neocolonial logic involving the responsibility to cleanse the damage of the high-emitter countries, which happen to be in the Global North, or otherwise service them through outsourced manufacturing.

AS:

So in a sense Kyoto was an act of levelling, between ‘overdeveloped’ nations and ‘underdeveloped’ ones to put it in crude terms. Instead of saying that the former need to under or re-develop themselves in different ways, essentially it created a speculative market in which carbon is now externalised and traded in stock markets by the latter.

DFP:

There are numerous books written about how you calculate carbon emissions, carbon storage, and the value behind carbon costs; how much a company needs to pay for a ton of carbon, etc. Instead of reducing pollution they just quantify how much money needs to be paid to keep polluting as much, if not more. You can even trade those rights with other nations that have very few factories, and magic, it balances out. That is the perversity of net-zero emissions. The system, created by the Kyoto protocol, has escalated especially since the 2007–2008 financial crisis, when many investors in housing were about to collapse, and moved into trading so-called ‘natural capital’. Today it has expanded from carbon to all kinds of species, whose level of conservation is now traded in a speculative market to profit from conservation quotas for some of these species.

JŽ:

And in city planning I find it quite disproportionate that a line of trees around a tall building could offset any amount of its environmental impact. Is it a game of aesthetics then?

DFP:

Yes, in the way it is. You could say that it is a capital gain. Basically, developers engaging with offsetting and mitigation schemes can just continue doing what they do, and pay a ‘compensation’. Different algorithms have been created to calculate the value of a tree. For example the tree in Nida, if you want to cut that down you need to replant 127 trees, because that’s its value according to some environmental report. And the people who defend this position argue that you cannot convince a decision- or policy-maker of its value unless it does not have an economic value attached to it. But the problem continues when you start calculating that value because you are ignoring human, social and many other values that are literally priceless. Why should it be quantified in the first place? We’d rather say: it needs to stay there. These are the main debates that have been around in the last decade: how to calculate value, but there is no point in doing it.

JŽ:

And you proposed to alter the structure of the law to give rights to the forests, the right not to be offsetted?

DFP:

It’s as simple as it sounds: granting trees rights for them to be considered as entities not to service humans or the city, and allow them to just be trees.

JD:

Have you sensed a different approach to trees and nature, and the forest through your work in the US and Sweden recently?

AS:

Yes, first of all trees have already been commodified and industrialised in Sweden for a very long time in a material way, and less in a financial way. One is timber, another is carbon stocks. The timber/forestry industry is so strong and prevalent in Sweden that when you speak about trees, their role as a commodity is what is driving the very physical conversation. Whereas in New York trees have a much more speculative meaning. What is happening now is an attempt to extract, and mine a new way to engage with the environment through the market of net-zero emissions to offset our environmental guilt.

JŽ:

While looking into the biofuel industry in the Baltics we recently realised that to simply stop burning fossil fuels, while using the same energy infrastructure, you have to replace fuel by cutting down a lot of forest. The process still releases the same amount of CO2, which is then captured with the replanted forest. In contrast to leaving the forest, burning the coal. The existing forest is not so quick to capture the CO2. It’s like a lie that leads to bigger lies?

DFP:

I agree. It is just pure greenwashing. Biofuels are quite problematic. First of all, because they erode the quality of the soil, do not allow other species to grow, and use a lot of pesticides in order to grow. Since they are not destined for food consumption, no one cares about the quantity of poisonous chemicals used.

AS:

Another interesting thing about greenwashing in regards to offsetting in a Swedish context is how it connects to the global carbon emissions market. There have been a lot of tree-planting initiatives, taking the clear-cutting model from Sweden into many nations in Africa. What was supposed to empower those nations in the postcolonial struggle for liberation and setting up their own economy, eventually turned into these carbon offset plantations in Mozambique, Uganda, Tanzania and many others, dispossessing people from their land for the sake of cleansing the carbon emissions of the Global North. One of the largest investors in Uganda for instance was the Swedish Pension Fund; a massive conglomerate. Last year it pulled out from all investments in African forestry due to growing pressure from citizens who did not want their life savings used to displace indigenous populations from their ancestral lands for the sake of carbon offsetting.

JŽ:

So the short term message – to offset the pollution, you aim to complicate that image and invite people to see all the other aspects of this model.

AS:

Yes, well, the main thing to do would be to stop polluting. Sounds logical.

DFP:

Because if offsetting had to happen on site, you cannot displace it, you would look into sorting out the problem. How to do that? It’s complicated.

JŽ:

How do you think about making the long term actual? So often in politics most important decisions are likely to be taken in the short term, within electoral cycles, and the long term question of natural systems becomes the elephant in the room.

AS:

Maybe we don’t have enough years of practice to answer it. But firstly, how do we define ‘long term’? What is becoming clear for us is that engaging with this question, trying to define it, pushes us to expand our understanding of ecology, whether it is offsetting or salmon. These are questions that have been unfolding for decades if not centuries, so trying to rethink and address them requires a really long time. We are curious to understand what it takes for a research project to have a long run. This goes against the way that cultural production currently operates in the entire field, which brings questions about legacy and what stays beyond and after exhibitions. How can projects change institutions? Their lifespan could be three, five, ten years which is already not enough time, as it needs perhaps 50 years minimum!

DFP:

Yes, I remember a soil scientist saying that if a plot of land has been polluted with all sorts of heavy metals for 50 years, that soil needs at least the same amount of time to be cleaned up. So when we start looking into these periods of time – pollution and clean-up time – the long term easily becomes 50 to 200 years.

AS:

The fact that there is not going to be salmon on Tate menus anymore is a way to start articulating that, but of course, there is much, much more work to be done. So I cannot say that we can already retire 🙂

JD:

Will the rights of trees have a continuation in the Swedish system of plantations?

AS:

This time we are trying to think not through carbon design but metabolic exchanges.

The legal system is interesting but has its limitations. In the Swedish context a lot of these lands were originally colonised, displacing or eradicating Sámi people from them. We recognise that there are limitations to what the law can do, even if there is political will, which many times is lacking.

Photographs

Offsetted, Cooking Sections (Daniel Fernández Pascual & Alon Schwabe), the Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery, Columbia GSAPP, New York. Photo by James Ewing, Courtesy GSAPP, 2019

Cooking Sections is a London-based duo examining the systems that organise the world through food. Using site-responsive installation, performance and video, they explore the overlapping boundaries between art, architecture, ecology and geopolitics. Established in 2013 by Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe, their practice uses food as a lens and tool to observe landscapes in transformation. They have worked on multiple iterations of the long-term site-responsive CLIMAVORE project since 2015, exploring how to eat as humans change climates. In 2016 they opened The Empire Remains Shop, a platform to critically speculate on implications of selling the remains of the Empire today. Their first book about the project was published by Columbia Books on Architecture and the City. They lead a studio unit at the Royal College of Art, London, and were guest professors at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich. Cooking Sections has been nominated for the 2021 Turner Prize. They were awarded the Special Prize at the 2019 Future Generation Art Prize and were nominated for the Visible Award for socially-engaged practices. Daniel is the recipient of the 2020 Harvard GSD Wheelwright Prize for Being Shellfish. Their latest book Salmon: A Red Herring is published by isolarii (2020) on the occasion of the namesake Art Now exhibition at Tate Britain.