Thinking Things Through a Forest

Jonas Žakaitis:

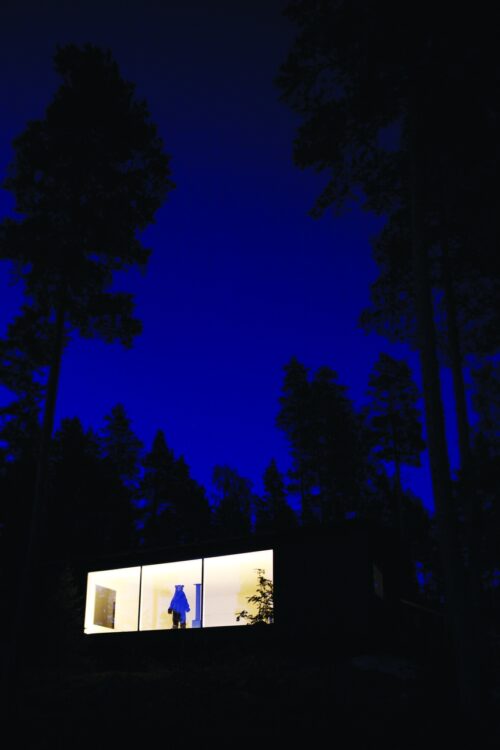

Dears. I don’t even want to count the years since the last time I saw you. I remember walking around the foundations of Kulttuurisauna with Tuomas, when it was just a crazy idea about to turn into bricks and mortar. Then I remember bathing in it a few years later, already full of steam and visitors, with Nene floating around, smiling and handing out towels like a friendly house spirit. I clearly remember our conversations then and how the sauna changed all of us that were involved – it started a life of its own and you both went along with it: your bodies, your daily routines, all of it morphed to live the life of that place. Not an idea, not a concept, but a real building with smoke coming out of it and people coming in to get warm. I remember how new all of this was to me at that time and how it was unlike anything I’d seen in contemporary art, my only lifeworld at the time. And then years and years passed. I heard about your daughter Aura coming into the world, I heard about the whole area around Kulttuurisauna changing and you guys inheriting a forest, but all these things are more like rumours. So I just want to start with a basic question: how are you doing? How is life?

Nene Tsuboi:

Greetings from Mäntyharju – we are staying at Tuomas’ sister’s house which was an old school building she bought five years ago. It’s still very wintery here with lots of snow – we’ve been skiing in the forest around the house, Tuomas cut some trees for next year’s firewood.

Our sauna in Helsinki has been sleeping since last December. We don’t know when we can reopen but probably not until late spring. Like last spring when we closed the sauna for four months, we’ve spent a lot of time at home, at the sauna and in the countryside. It was good for us to have a holiday from the sauna routine, which at one point was beyond our capacity. It became too popular and we didn’t even realise how insane it was to have nearly 100 bathers everyday. Because one of us had to take care of Aura at home, running the sauna was almost a one person operation for the last couple of years.

After the Covid closure we reopened the sauna last midsummer and introduced a new timetable – the sauna was open only in the mornings. At 7am we opened the door and at noon it was closed. We wondered if anyone would come (we had the very same feeling when we opened the door for the very first time in spring 2013!). But they did, and it was the perfect amount of bathers (around 20 per day). In the mornings the courtyard gets lots of sun and the bathers could see the sunrise while swimming. It was always peaceful. Plus, we introduced a new rule: silence indoors to reduce aerosols (people can chat in the courtyard). We recommended the bathers bring their own towels, seating linen, and water bottles for hygiene reasons and that reduced our dishwashing and laundry work too – perfect. Our work was done by early afternoon and both of us could stay at home with Aura in the evenings. The idea of a morning sauna had existed for some years but the Covid situation made it possible to make this shift really smooth.

JŽ:

So I’m very curious to hear about the visitors to your sauna – especially the regulars. Who are the people coming to the sauna every week? Is it mostly people from your area? Have you got to know them over time and have they shaped your daily sauna routines and traditions in any way? And do you get to hear your visitors’ stories?

NT:

It took me a while to get back to my sauna mindset after our routine was ‘off’ for almost four months… but once I access that part of my brain it’s there and very much alive. All of our customer information is based on our face memories:

– Super regulars (about 10 individuals who visit 2–3 times a week)

– Solid regulars (about 60 individuals who visit 1–2 times a week)

– Regulars (about 150 individuals who visit once every 2–3 weeks)

– Seasonal regulars (about 100 individuals who come in either summer or winter)

We don’t know most of their names, so between me and Tuomas we use nicknames for them. We know lots of them live and work in the neighbourhood, except some of the super or solid regulars that live in other cities (even in Tallinn).

Tradition and routine is definitely created by the regulars over the years. Regulars also recognise each other since most of them come on the same weekdays and time. The most popular discussion topics between them are about the weather and nature. They want to tell each other whether the sea feels cold or warm, about the direction of the wind or which birds they have seen in the courtyard. Everyday has different conditions so they never run out of things to talk about. It is also a form of politeness between the bathers, even if you are a first timer or a child, you can follow the conversation. For us it’s very important that bathers come as individuals and not as teams – when people come as groups, this delicate balance of shared space and time with others is easily destroyed by people bringing their own relationships. In Finland there are so many saunas available to enjoy with close family and friends, so we are trying to keep the publicness of the sauna as strong as possible at our sauna.

But right now, having discussions with strangers in public indoor space feels like something from another universe! I’m really curious how public sauna culture will evolve from here on…

JŽ:

This is so beautiful! I’ve never thought of small talk about the wind and water as being the most open handshake of socialisation. I don’t know why, but it made me think about colonies of penguins squeezing together and flapping their wings – maybe they’re doing the same thing?

And speaking about changing conditions – have you noticed any subtle differences in the way bathers move and behave with the changes within your daily routines, say with the music you play or the type of wood you burn in the stove? Maybe just barely perceivable changes that you feel, because you are so in tune with the sauna’s rhythms.

Tuomas Toivonen:

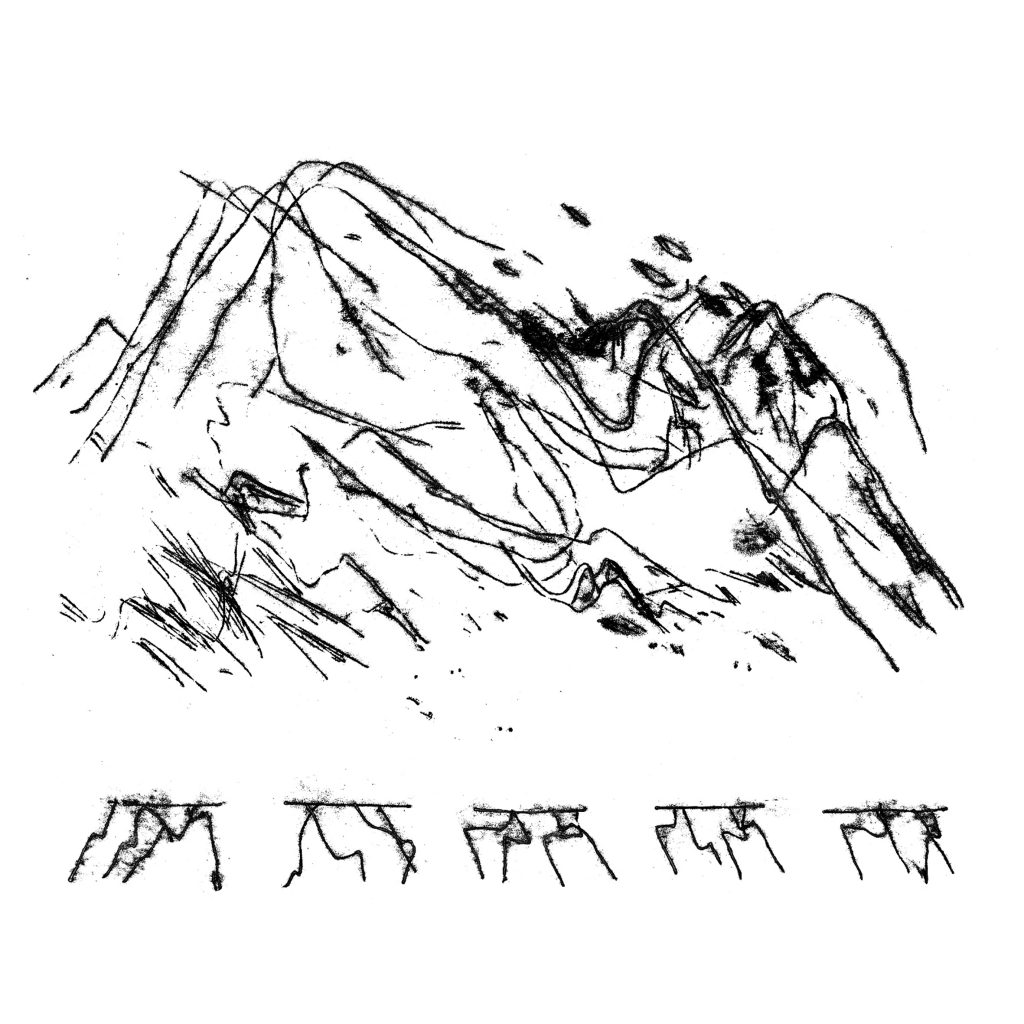

We realised that what we play in the building definitely affects bathers behavior. We quickly realised that having no sound or music in the space makes the atmosphere too unsteady. Especially in the early years when there weren’t the rituals by regulars – it’s really hard to set the right mood. From the moment that someone steps into the building, they need to understand that the sauna is a kind of sacred space (to reinforce that we also have a ‘take your shoes off policy’ at the entrance). In the first year we played the soundtrack to Fitzcarraldo by Werner Herzog and old recordings of Enrico Caruso, because the construction of the sauna felt like pulling a ship over a mountain. But the most crazy feeling was after the construction phase was over: we immediately switched our role to sauna operators, I think it was even within the same day – in the morning we gave the construction a final push and by the evening our first bathers arrived. It was just too extreme a change. At the construction site the tasks are different at every stage and you need to fight with new problems cropping up all the time. But all of a sudden our life involved doing the same thing at the same time. I think playing ‘Fitzcarraldo’ was a kind of way to make the change smooth for us (we still play ‘Fitzcarraldo’ on May Day, the sauna’s anniversary). Then in the second year was Claudio Monteverdi’s ‘L’Orfeo’ which is one of the earliest opera ‘works’, which we played for a year and half I think…Then we started to play orthodox monastic music from Valamo and Ambrosian chants for almost for a year, then erner Durand’s ‘Hemispheres’. Up until this point the medium was vinyl, and the player was in the office, so every time the record ended, we would go out to the courtyard, into the office and flip the record, about 15 to 20 times a day (if we were busy there would be silence until we got the chance to go and put the music on again). This was, in a way, a very laboursome method, but it felt right, and it was important to visit the courtyard to check on things, swimmers, the slipperiness of the deck, pick up the mugs that people had left etc…

Then, Aura was born and after some time, the Durand record was replaced by a more experimental setup with a constantly changing generative ‘soundfield’ playing from various speakers in different locations behind the wall, connected to various sound sources (some kind of complex, parallel autonomous synthesizer setups mostly) but tuned to a non-standard pentatonic scale based on 50 Hz, which is the tone of the electric grid – and also the pitch that is in tune with the ventilation machines, the coffee grinder, the vacuum cleaner or the fans of the pellet burner… and the idea is to ‘conceal’ and ‘musicalise’ the sounds that are in the building anyway. We have also had some live performances behind the wall, but without announcing to anyone that the music is live… so if someone comes to ask ‘What’s this music today?’ only then do they find out it’s live and who is playing…

I think a lot of this electronic soundfield material didn’t sound much like ‘music – but it was very effective in creating a mood that somehow ‘tensioned a silence’ which is why it felt right. From the beginning we used music as a kind of ‘traffic sign’ that a visitor would encounter at the door – putting them on alert that ‘Ok, things are somehow strange here, I’m not sure what kind of place I have just stepped into, better slow down and look at how other people are behaving, and maybe then figure out what’s going on and how everything works’. Over the years our bathers have become super regular so somehow we could also start taking them to more ‘challenging’ or unusual directions, and this made sense as the place was risking becoming (from our point of view) too popular, so this tensioned atmosphere and constant drone rumbling from beyond the room was one way to give off a vibe that was not too welcoming and then people who came often developed a taste for it.

The wood we are burning is normally pellets; they burn very efficiently and give off quite a subtle scent. But we burn logs as well; each wood has a distinct aroma. Birch is the classic, rustic smell, aspen and ash are a bit more refined and sophisticated. Pine and spruce are more tarry and have an oilier resin-component in the smoke. Sometimes I make a roll with some juniper bark and copper wire to burn slowly over a candle and make it smoke as incense; it has a very aromatic, vapoury, holy scent.

JŽ:

Tuomas, reading your reply, I couldn’t help imagining the sauna itself as an abstract soundscape. And how this soundscape is a mix of rhythms of different orders – the 50 Hz of your music, the oscillations of the nervous systems of the visitors, the cycles of daily routines in the building and the changing seasons. Different orders and totally different scales, but all affecting each other. Sort of like the Covid-19 virus these days: does it have a scale at all? It’s supposedly a nanoparticle (around 10 Hz, btw, just googled it!), but it incorporates planes and crowds of people and state borders. So it’s sort of really basic as an organism, but it’s so good at using human infrastructure that the whole nature/culture distinction is just not practical if you want to deal with it. Which (it’s a leap, I know, I know) makes me think of the text you wrote back in 2018 on the plot of the forest you inherited and how you wanted to let it grow ‘wild’ again. Would we even know what that means? Or, to get more speculative, maybe the forest is much more like a virus – maybe it’s not even a definite body and it does not act on any one given scale? Do you go to that piece of land often? How has it changed since your first visit?

TT:

Yeah, for me music or sound has no beginning or end, and it’s a way to adjust and align everything by getting things to resonate together… and the 50 Hz frequency stands for the resonance frequency of human systems and culture, its infrastructures and networks, an organism. And to make that legible with all its tensions and contradictions is a kind of ‘project’ that has emerged in the music programme and recent music projects… here is an example of this non-ending resonance feel:

– it’s a kind of sound field that an organism makes (in this case a complex system of synthesis), that reacts to simple inputs, and simulates its reactions in a linear time audible form.

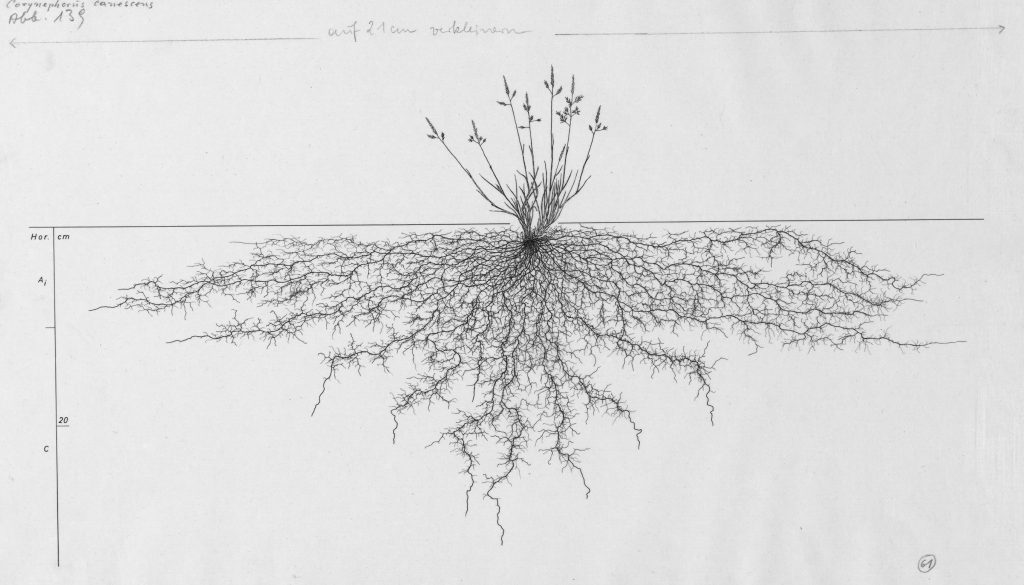

The forest is also an organism, or system, and I think this nature/culture divide that you mention is crucial, as it questions how we are – or are not – part of that system. All species are invasive, but they are often invasive together, and need to find ways to coexist and ‘live’ as they terraform a mineral landscape and atmospheric chemistry with solar energy into something that suits them better – but the organism of human culture is seldom aligned with the way these natural systems have evolved, and along these misalignments, we can trace the nature/culture divide. Of course, this is now a super topical and urgent matter, as we have to quickly begin steering this human-cultural organism to avoid massive damage and threat to the natural systems – but for sure ‘natural systems’ will prevail in every case, though we may still lose the complex systems like forests that have become so sophisticated. And my realisation has been that we already lost the complexity in most of nature long ago, so either we retreat back and see the kind of order that establishes itself, or take an active role in assisting or ‘playing’ (not play as in a game or play around but play like someone would play an instrument) the system for responses, so we understand its potential and character. But every model is incomplete; I don’t think these systems (human or natural) can be reduced to cybernetic, or computational models…and I’m sceptical of gaia theory as well. I think a kind of hands on science plus curiosity plus animism that involves a dimension of respect could be the way to collaborate – not extracting or hacking individual aspects – with these systems; to change and learn both our own understanding and relationship to them, but also give them ‘offerings’ by working for their benefit, or trying to amplify and foster certain mechanisms and behaviours (like leaving an animal or tree carcass where it fell, not extinguishing a forest fire, or bathing together or enjoying atonal harmonies, or wearing a mask or not speaking if not wearing a mask during a pandemic).

That forest is different every time I visit, as seasons and weather and time pass – but also I’m slowly getting to know it better in detail, its rocks, trees, undergrowth patterns, and its edges, the animal tracks that pass through it in winter…I wish that time would pass faster, and it would get ‘older’ quicker, but I guess Aura will see it. I think the oldest trees are about 150 years old – very thick and tall spruces and a few dozen kelo (dead, dried pines that are still standing). Animals: all kinds of insects, squirrels, birds, bats, forest mice, vipers, rabbits, a fox and even a lynx pass through. They don’t know where one land boundary begins and another ends, but they clearly prefer moving in the least silvicultural parcels of the forest.

JŽ:

There’s a lot to think through in your last reply! And maybe there is a difference in me thinking about a forest and you owning part of one. It’s one thing to think about nature as a complex system (which it kind of is) and another thing to see how animals and plants move about in an actual place and how your intervention actually changes that. And your triad of hands-on science + curiosity + animism is a truly great proposal. In my mind it folds together a genuine care for something (a forest, a sauna, a community?) without pretending to know or control it. Which is kind of what we need right now, no? I’m also curious to know whether becoming acquainted with that piece of land has changed your architectural practice in any way?

TT:

So far my relationship with that parcel of forest has been very passive. I like to visit during different seasons, and little by little get to know its character and places, its rocks and trees, its constants and its changes. To date I have taken the approach to not cut any trees, I have ‘denied’ its dimension as a source of raw material – wood – that is an asset that can be sold or used in several ways. Since almost all forests in Finland are silviculturally managed ‘tree plantations’, this passivity becomes a contrasting gesture – passivity as an active stance. As the forests around us are cut and replanted, my woods will remain and develop into an island with older specimens and more complex relationships between flora and fauna.

From the perspective of my architecture practice I have also started looking at wood in a new light, some of these tendencies are perhaps influenced by thinking things through a forest:

– I prefer to use wood in a way so that it performs at its best – I want every 2 x 4 in a light stud frame to be working hard on its coordinated and individual tasks instead of having a mass of cross-laminated timber (CLT) with a heavy volume of glue and ‘minced meat’ whereby the trees have lost some of their potential and dignity. On the other hand, for fast-growing tree plantation stock, the CLT form is more forgiving, the material’s structural qualities are no longer that important.

– For building the sauna we used logs as pillars. We went to see these trees before they were felled. Even though the land where they grew lost these handsome pines, the way they are used in the building retains their log-ness or tree-ness. The columns remain fragments of the forest of their origins, and we can tell their individual stories. On some level, this applies to every piece of wood. Each piece of sawn timber comes from somewhere, even if its shape has been standardised and no-one knows anymore which piece of land it was cut from.

– Every old building made of wood contains a forest – we can see it as a set of individual trees cut from specific locations and brought together. When moving though forests in Finland, the lack of old growth forest and old trees becomes apparent quite quickly. Those trees were cut. They were used. The best trees were used for construction. they became buildings, furniture, architecture. Looking at Timo Penttilä’s cabin near Sevettijärvi, we can see a building made entirely of massive logs from old kelo trees. Or we can see the surrounding slow-growth forests that are now missing these old trees. In this light, architecture can appear grotesque. Every design is a plan for a massacre (clear-cut) or at least an abduction (the extraction of single logs), every building becomes a nature morte, a trophy, or ossuary of a forest. Naturally this is not only the case for wood, but for every part of a building, especially ones that are made of virgin materials.

– Nothing is neutral and everything is problematic. Perhaps at the core of our life and work is the question of how to make compromises while caring about things – how to make sense of complex perspectives, contradictions and tensions.

Jonas Žakaitis is a writer, running coach, and physiotherapist based in Vilnius. He previously worked as a gallerist, philosopher, and curator. He is the author of a collection of short stories called 90s, inspired by life in 1990s Lithuania.