An Epitaph for a Fakir of Lithuanian Music

In late 1999, the editors of the cultural and arts magazine Kultūros barai organised a survey of musicologists to identify the most significant and influential work of Lithuanian music of the twentieth century. The clear leader in all top five lists compiled by musicologists of different generations and tastes was Bronius Kutavičius’ (1932–2021) oratorio Paskutinės pagonių apeigos (Last Pagan Rites), which premiered in 1978, during the dreariest years of Soviet stagnation. I didn’t get the chance to witness the first performance of the oratorio firsthand, since I was still in primary school at the time, but after several decades working for Lithuanian Radio and TV and conducting numerous interviewers with performers, composers, and artists in other fields, I’ve listened to many accounts of that evening, which has been described invariably as an artistic, but also cultural, almost existential shock so profound that it became an indelible part of the memory of those who were there at the time. In my own imagination, the threads of different accounts have intertwined into such a fantastical experience, that I almost feel I was there myself. Whenever I listen to that first recording of the oratorio, those images wash over me, as if they were my own.

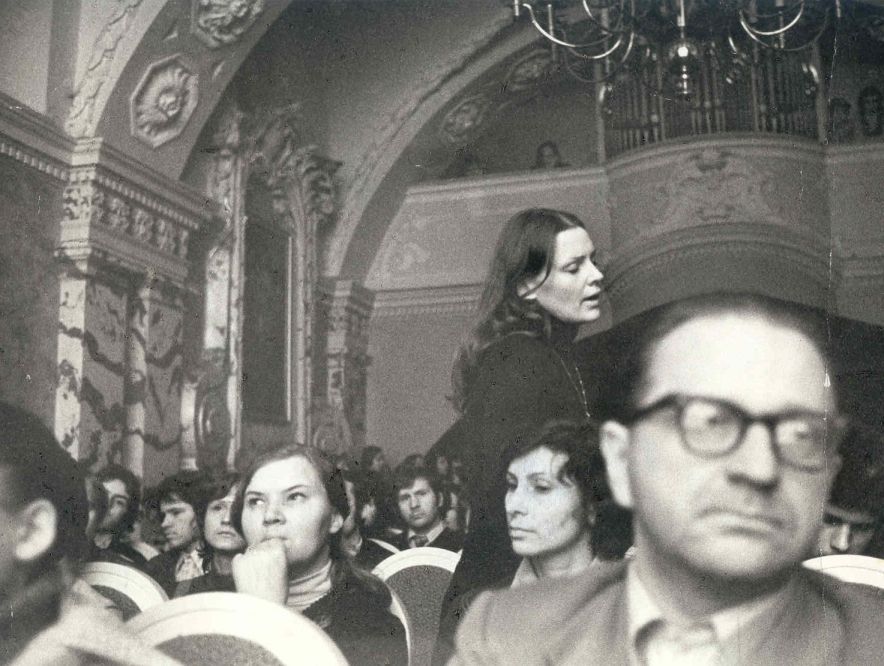

Musicologist Vytautas Landsbergis (later the first leader of the restored independent Lithuanian state in 1990), who was once active as a music critic, observed: ‘On the last evening in November, the Small Baroque Hall¹ was full of listeners, although none of them had been drawn to attend by any posters or press notices. An extraordinary bit of news had circulated among musicians about a regular “hearing” held by the Composers’ Union,² and it was then picked up by music lovers, some of whom sensed that the new work by Bronius Kutavičius was turning into a cultural event that could not be missed.’³ Indeed, Kutavičius had already become popular as an artist in possession of a unique and inspiring imagination. Much like a soothsayer, with Last Pagan Rites he relied more on intuition and the intonations of the oldest Lithuanian folk songs than anthropological sources to recreate pagan rituals of nature worship. This impression was reinforced by a children’s choir that walked in a circle around the audience, creating a mobile, shimmering, spatial sound effect. In the finale, the minimalist, hypnotic flow of music is harshly pierced and eventually overwhelmed by the tunes of organs – a symbol of Christianity. The audience became completely still as they listened to the ever more powerful chords of the organs. Giedrė Kaukaitė, a soloist in the ‘Incantation of the Serpent’ scene of the premiere performance, recently wrote about her impressions: ‘The score, resembling a graphic drawing, showed the “Incantation” piece in the middle of the drawing, but during rehearsals we debated at length where the soloist’s place should be during the performance. Facing the audience, as per tradition? No. Behind the organ? In the quire? No and no. Perhaps among the choristers? No, I’ll stand among the audience, out of costume, as one of them, and rising up from among them I will sing five segments of the “Incantation”, turning with each one to a different part of the world: east, west, south, and north, and then again to the east. I picked a seat in the middle of the hall, with half the audience in front and half behind me. Interestingly, not a single person sitting in front of me turned back to look when they heard a solo being sung behind them… I remember the experience of that first performance like a miracle. The faces of the audience in a surviving photograph by Algimantas Kunčius reflect a state of “speechlessness”. The idea of the opus has been described as a clash between the pagan faith and Christianity. But the concept is actually much broader, summing up the entirety of any enslaving, brutal force and power. We understood the organ chant as a metaphor – an enormous, heavy claw of a predatory beast, strangling us alive without mercy. On the day of the premiere, sitting off to the right in the Baroque Hall was a long-time friend, the sculptor and poet Vytautas Mačuika, who had been sentenced for underground activities, spent ten years in a prison camp, escaped twice but was recaptured, attacked by dogs, and only released after Stalin’s death. Mačuika kept his head shaved for the rest of his life, in protest, to remind himself of his life as a prisoner. At the start of the oratorio, not even halfway through the “Grasshopper” section, Vytautas leaned forward, rested his elbows on his knees, and hung his head, never lifting it again until the end. As the oratorio came to a close, he slowly rose again, as if he’d been whipped.’⁴

Kutavičius’ powerful, communicative work overcame the barrier of distrust and audience aloofness to contemporary music, bringing together not only the music community, but also poets, artists, theatre professionals, and intellectuals, inspiring new reflection and the search for more powerful and sensitive forms of writing about music, and analysing the cultural context of musical works. But to the communist regime and the overseers of art Kutavičius was an outsider and hadn’t been spoiled by the privileges enjoyed by other artists who occasionally fulfilled government commissions, glorifying communism and the Soviet system with their work. Moreover, censors ‘advised’ music critics not to write too often about Kutavičius or other prominent composers of that generation such as Feliksas Bajoras (b. 1934) and Osvaldas Balakauskas (b. 1937).

Paradoxically, the most prominent composers – Kutavičius and Balakauskas – were rejected by the Soviet Lithuanian State Conservatory (today the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre) as unpromising and lacking talent. Balakauskas then left to study at the Kyiv Conservatory and Kutavičius was drafted into the Soviet army, after which he was accepted into the Vilnius High School of Music. Only in 1959, at the age of 27, was he finally admitted to the Vilnius Conservatory. His early works, like those of most composers of his generation, were heavily influenced by the avant-garde, since, with the easing of the political climate in the 1960s, it became possible to attend the Warszawska Jesień (Warsaw Autumn) festival, the most important forum for new music in Eastern Europe. After Stalin’s repression and brutal censorship, the experience of Warsaw, freer and more open to Western culture, became more important than official studies for young composers.

Most of the Lithuanian composers of the middle and younger generations at that time experienced the ‘Warsaw shock’. Their creative work, until then impeded by the doctrine of Socialist Realism with the ideals of the Dmitri Shostakovich style, suddenly exploded with avant-garde techniques and aesthetics. Western compositional scores were smuggled in from Warsaw, and then secretly studied and sometimes plagiarised. Eventually, composers had their fill of the ‘forbidden fruit’ and Kutavičius became ‘burnt out’ by the avant-garde fairly quickly. His name is associated with a true and profound renewal of Lithuanian music after the 1970s, when the ideas of cultural resistance, national identity, and creative freedom began to strengthen. Indeed, the 1970s was a time of searching for identity in the music of the Baltic countries. On the one hand, composers of that generation were searching for a unique, individual musical expression. On the other hand, the need for ideas and values capable of unifying artistic communities also grew. Official Soviet doctrine proclaimed the arrival of a period of ‘mature Socialism’, but in art the ever-stronger voice of the individual and the herald of the nation gradually gnawed at the system’s foundations, awakening in society a longing for sincerity, communion, national traditions, spirituality, religiosity, and freedom.

Kutavičius’ point of departure as a Lithuanian cultural guru was his 1970 Panteistinė oratorija (Pantheistic Oratorio), a distinctive instrumental theatre in the form of a wild and primordial ritual, inspired (like his later Last Pagan Rites and many of his other vocal works) by the verse of Sigitas Geda (1943–2008), a moderniser of Lithuanian poetry. The unconventional oratorio genre would later become Kutavičius’ signature style, but at the time he still had to overcome government resistance. Kutavičius’ legitimacy was considerably bolstered by the previously referenced reviews by Vytautas Landsbergis, who had already secured his place as an authority on the painting and music of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis (1875– 1911). The ranks of Kutavičius’ admirers, performers, and defenders were actively joined by the alto player Donatas Katkus, the founder of the Vilnius Quartet and the St. Christopher Orchestra, who had become a prolific music critic thanks to the power of Kutavičius’ music. Katkus recently reflected back on that time: ‘We did all of that not for the good of society or Lithuanian music but wanting to defend those composers since we saw that fantastic things were being born. I’ll never forget when in 1970 Kutavičius’ Pantheistic Oratorio was performed in the Philharmonic Society’s Chamber Hall. The older composers and party activists simply tore into it. After the performance, in the corridor, I went up to Bronius, who no longer looked like a human being, and said: “A work of genius! Don’t listen to them! They don’t understand anything.” I saw Bronius’ face light up! People like him needed support so they wouldn’t give in, so they would believe in their talent. They only needed a few people whose opinion mattered to them.’⁵

Kutavičius began to produce significant works, one after another: Dzūkiškos variacijos (Dzūkija Variations) for a folk singer, choir, and string orchestra in 1974, Mažasis spektaklis (The Small Spectacle) for an actor and ensemble according to verse by Geda (1975), his cantata for soprano, ensemble, and tape recorder, entitled Du paukščiai girių ūksmėj (Two Birds in the Shade of the Woods) based on the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore (1978), and the cult-like Last Pagan Rites, etc. Like an anthropologist or prognosticator, Kutavičius would recreate the rituals of archaic civilisations, primal folk song imagery, a vision of the World Tree, or shamanic ceremonies. And people believed in him, trusting his intuition, joining him on a journey down reconstructed paths of visions from the past. Kutavičius became a fashionable icon of modern culture, and discussions of his work began to include descriptions formulated in Landsbergis’ texts, such as ‘a Lithuanian fakir’, ‘a cultural substratum of music’, ‘simple and strong music’, etc.

In their day, Kutavičius’ ideas appeared unique, but we know now that similar trends founded on historic roots, archaic imagery, and national cultural values were also manifesting in other Eastern European countries. Prominent analogous examples of Kutavičus’ work include his contemporaries, the Estonian composer Veljo Tormis (1930– 2017) and Lojze Lebič (b. 1934) of Slovenia. Today, we understand this phenomenon as part of a silent cultural resistance being waged in the occupied countries of Eastern Europe. While the West recovered after the traumas of the Second World War and life and art began to enjoy the emergence of a sense of order, structure, playfulness, and consumerism, people on the other side of the Iron Curtain scoured art for solace, support, and a safe haven from the harshness of Soviet reality. Eventually, the meditative, resigned work of Baltic composers (Kutavičius, the Estonians Tormis and Arvo Pärt, and Latvians Pēteris Vasks, Pēteris Plakids, et al) came to be known as ‘Baltic Minimalism’.

Although news about Kutavičius had already reached the music communities in Latvia and Estonia in the 1970s, thanks in part to the close cultural cooperation enjoyed between the three Baltic republics and jointly organised musicology conferences, presentations of Lithuanian music in the main cultural centres of the Soviet Union (Moscow and Leningrad – now St. Petersburg) centred around different names. On the one hand, this was because Kutavičius avoided commissions glorifying the Soviet regime and the Communist Party, but also because the leadership of the Composers’ Union and the Lithuanian Communist Party didn’t perceive his style to be representative or worthy of performance on leading stages by prestigious orchestras. Kutavičius’ works also weren’t included in the programmes of official Lithuanian ensembles (orchestras, quarters, etc.) on their tours of Eastern Europe. In truth, his Dzūkija Variations were unexpectedly incorporated into the repertoire of the Lithuanian Chamber Orchestra led by Saulius Sondeckis, the most prominent Lithuanian ensemble of its day, enjoying exclusive opportunities to tour in the West (under KGB supervision, of course). On that occasion, the prestigious orchestra had prepared one of its best-known programmes: Tabula Rasa, by Estonian Arvo Pärt, the target of Soviet government persecution, and Concerto Grosso No. 1 by the so-called ‘Moscow underground’ composer Alfred Schnittke. The programme only lacked a short work to fill out the full concert format. The lovely Dzūkija Variations soon came to mind. Such was the programme that the orchestra presented in 1978 in the three Baltic capitals and at the Warsaw Autumn festival, and the following year during a tour of numerous cultural centres in the West, including the United States.

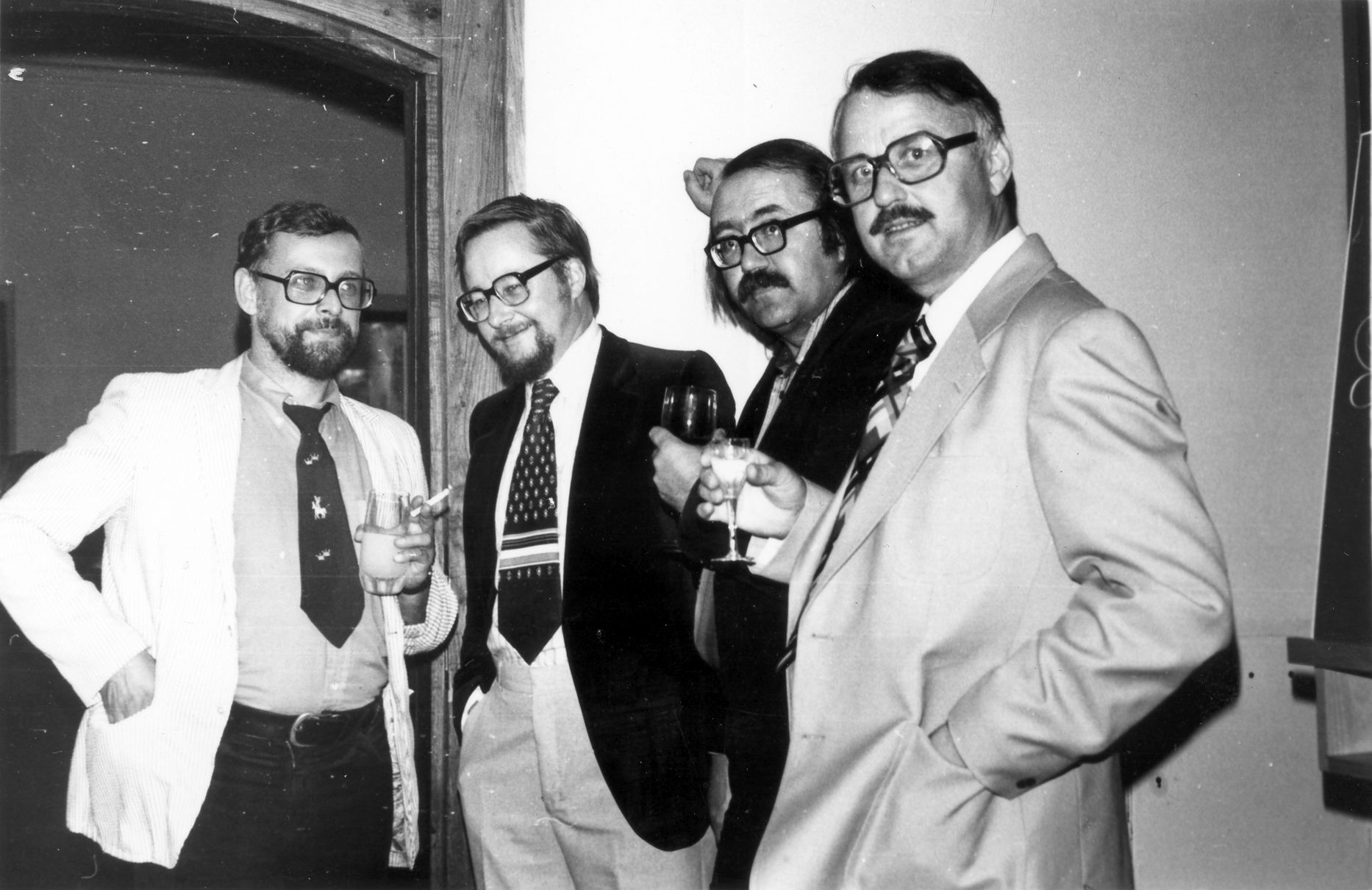

For Kutavičius personally, the ice was broken in the late 1970s in Poland, after Landsbergis established ties with Polish musicologists and struck up a close friendship with his younger colleague Krzysztof Droba (1946–2017). On his first visit to Vilnius, Droba listened to a considerable amount of Lithuanian music and made friends among composers, inviting them to the informal festivals he curated in Poland. Katkus recalls that, after Droba first heard a recording of Last Pagan Rites, he stood up suddenly and asked where the bathroom was. It turns out he needed a place to cry, away from others – so profoundly had the music impacted him. Droba was a young, non-conformist who ignored the official Soviet musical export offerings and organised intimate, close-knit festivals in small Polish towns.

Kutavičius was the first to receive a commission from Droba, which led to the creation of one of his most frequently performed opuses, String Quartet No. 2, Anno cum tettigonia (A Year with the Grasshopper), composed in 1980. The grasshopper was that year’s symbol in Japanese mythology. In this quartet piece, time is measured precisely, consisting of 365 beats (days), with the rhythm shifting every seventh beat, and the shimmering string fabric pierced twelve times by the ringing of a bell. The string intonation and articulation resembles the sound of archaic Baltic wind instruments called skudučiai (panpipes). The form of the work grows like the path followed by the sun to its midsummer culmination and gradual distancing from it. This masterful, hypnotic piece is deservedly considered a classic of Lithuanian minimalism.

Kutavičius first attended one of Droba’s festivals in Stalowa Wola in 1979, which featured a concert of his work, including a performance of the new quartet. In later years, Droba invited Kutavičius to festivals he organised in Baranowo and Lusławice. It was thanks to Droba that Kutavičius became acquainted with Krzysztof Penderecki. These connections also brought him to the Warsaw Autumn festival, where a concert of Kutavičius’ works took place in 1983, including Last Pagan Rites (which Kutavičius himself did not witness because he was prevented from attending by Soviet officials), and in 1988 in Sandomierz, the performance of three oratorios with the participation of the Vilnius New Music Ensemble, organised especially for Kutavičius’ works. This was already during the time of the Baltic rebirth and its ‘Singing Revolution’, and the Soviet government could no longer suppress the breakthrough of Kutavičius’ music. The Vilnius New Music Ensemble was founded by Šarūnas Nakas, one of Kutavičius’ former students at the M. K. Čiurlionis School of Art, and today a renowned composer, multimedia artist, and radio programme director. ‘When I was a child, I’d run from Kutavičius’ lessons – they were boring,’ Nakas later remembered. ‘Everything changed after I, at 16, was able to attend a performance of Last Pagan Rites. That night, everything changed.’ While studying composition at the Conservatory, 20-year-old Nakas decided that it was finally time to perform Pantheistic Oratorio, which had never again been publicly heard after the previously mentioned less than successful performance in 1970. Nakas gathered together his student friends and, in December 1982, organised a premiere performance of the oratorio twelve years after its unsuccessful hearing. One year later, inspired by the enthusiasm and interest of the young performers, Kutavičius wrote a new oratorio for a vocal ensemble and ancient and unconventional instruments (stones, bottles, skudučiai panpipes, a lumzdelis flute, a straw pipe, the kanklės string instrument, violin, and harmonica) entitled Iš jotvingių akmens (From a Jotvingian Stone). The oratorio begins with the beat of actual stones, as if invoking the Jotvingian spirit [The Jotvingians inhabited an area to the south of the current Baltic states stretching from present-day Poland east into Belarus – Ed]. The work reveals the growth of national self-awareness and creativity, from its primal impulses to folk songs as a perfect and vital form of beauty. ‘What Kutavičius does is not just music – it’s things that can be incorporated into life. We as performers wouldn’t have lasted six months if our work was just a dry recitation of score. This integrates the entirety of culture. This music changes the way we think and encourages us to grow. It helps you realise that the work you put into bringing a score to life is meaningful, because that effort makes up for the longing for values. For us, it offers a direction for how to live, a way of living and communicating,’ Nakas said at the time. In 1984, the ensemble performed a concert of Kutavičius’ works to great success at the Riga Philharmonic Hall, followed by the previously mentioned tour in Poland, but Kutavičius’ true breakthrough in the West came after Lithuania restored its independence in 1990. In that time, the ensemble had assembled a larger repertoire of works by Lithuanian composers, beyond just Kutavičius. After the collapse of the Iron Curtain, the first presentation of music by Kutavičius, Balakauskas, and the younger Algirdas Martinaitis took place in 1990 at the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival in the United Kingdom, where participating curators of other festivals became intrigued by the exotic sound of unknown music emanating from a small country freed from Soviet shackles. For that occasion, Kutavičius composed a new oratorio for Nakas’ ensemble, titling it Magiškas sanskrito ratas (The Magical Circle of Sanskrit). Invitations to other European new music forums soon followed, one after the other. The ensemble appeared at the Baltic Composers’ Peace Days in West Berlin, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, and in the autumn, reprised their concert of Kutavičius’ oratorios at the Warsaw Autumn festival. In 1991, they participated in the NYYD Festival in Tallinn, followed by concerts in Lviv, Prague, and a tour of Canada, appearing at the Victoriaville festival in Quebec and giving a special concert at the Le Spectrum Center in Montreal. The ensemble’s pilgrimage with Kutavičius’ music continued in 1992 in Warsaw, Amsterdam, Cologne, Seville (at EXPO ‘92), Düsseldorf, Strasbourg, and a series of Danish cities. The next year, the ensemble presented Kutavičius’ music at the Hammoniale festival in Hamburg. Captivating and memorable performances followed in 1995 at the Prague Spring Festival and at a festival of Baltic music at the Southbank Centre’s Queen Elizabeth Hall in London.

The final presentation of Kutavičius’ music took place at the 1996 Easter Festival in Innsbruck, Austria, after which the Vilnius New Music Ensemble disbanded. After fourteen years of active performing and expanding their repertoire, the ensemble’s musicians had become disillusioned by the uncertainty of their situation. The first decade of Lithuanian independence was a time of complicated social, political, and economic processes, made worse by a lack of funds and stalled reforms. While the ensemble had reached maturity and attained a high level of professionalism and international recognition, it still lacked institutional and financial stability. Having embarked on their effort with such enthusiasm as students, the ensemble members grew older, started families, and could no longer be satisfied with occasional invitations and earnings. Indeed, because all state-sponsored and national arts groups had a difficult time surviving during this complicated period, no effort was made to seek official status or financing for yet another such ensemble. And what a shame! Some groups had exhausted their energies and failed to adapt to the new circumstances, but more effective reform of the cultural sector was abandoned both out of inertia and because of the resistance by cultural officials left over from the Soviet period. But the Vilnius New Music Ensemble performed an important role in the inspiration and dissemination of work by Kutavičius and other talented Lithuanian composers, helping also to consolidate standards of new music performance and educating audiences.

Kutavičius’ works expanded during this period, and his visions transcended the limits of a small ensemble. He also began to receive commissions from various festivals. His most prominent works from this period include a four-part series, created over several years, entitled Jeruzalės vartai (The Gates of Jerusalem), reflecting on the history of world religions from northern shamans to Western Christianity – consisting of Žiemių vartai (Northern Gate) in 1991, Saulėtekio vartai (Eastern Gate) in 1992, Pietų vartai (Southern Gate) in 1994, and Saulėlydžio vartai (Western Gate/Stabat Mater) in 1995. In 1998, commissioned by the Musikhøst Festival in Odense, Kutavičius created a monumental oratorio entitled Epitafija praeinančiam laikui (Epitaph to a Passing Time) reconstructing the history of Vilnius from the legend of its founding as a dream seen by Duke Gediminas in the fourteenth century, through the founding of Vilnius University in the sixteenth century, to a lamentation of the victims of Stalin’s gulag, to the return of Vilnius Cathedral to the faithful.6 The oratorio was later performed at the Vilnius Philharmonic (and broadcast to EBU countries), at the Warsaw Autumn and Prague Spring festivals, and released on CD by the Finnish label Ondine.

At the time, the young Czech musicologist Vítězslav Mikeš became intrigued by Kutavičius’ music and grew to love it wholeheartedly. Wanting to gain a deeper appreciation of the composer’s work, he learned Lithuanian and even defended his dissertation at Charles University in Prague about the relationship between text and music in Kutavičius’ works based on the verse of Sigitas Geda. Thanks to Mikeš, Kutavičius’ works have been performed regularly at various Czech festivals and contemporary music forums.

Among Kutavičius’ most prominent later works we should single out the opera Lokys (The Bear), commissioned for the Vilnius Festival (and performed in 2002 at the Lithuanian National Opera and Ballet Theatre), based on a novella by French writer Prosper Mérimée, in which nineteenth century Žemaitija (Samogitia, in western Lithuania) is depicted as an exotic and barbarian land, a backwater of civilisation, where reality intertwines with pagan mythology and magic and eerie stories enfold. But for librettist Aušra Marija Sluckaitė, the novella served only as a framework for the narrative, and she refrained from emphasising the encounter between the barbaric and civilised worlds: The heroes of the opera ascend to the realm of myths. Kutavičius confessed that he had long dreamed of creating an opera in the style of the nineteenth century, with a large orchestra, choir, and ballet. And, indeed, in this work, as never before, he respected the conventions of the genre, but didn’t try to follow any historical or modern opera model, and instead returned to its fundamentals: the connection between text and music. As in his other works, the essential characteristics of his music are its pulse and recurring melodic motifs. For September 2022, on the occasion of Kutavičius’ 90th birthday, the premiere of Lokys at the Klaipėda State Music Theatre was prepared by director Gintaras Varnas, who has earned a reputation as an exceptional master of opera directing. This is a much-anticipated highlight of Kutavičius’ jubilee year.

Among Kutavičius’ other works created in the twenty-first century, another standout is his monumental series Metai (The Seasons, 2005–2008), based on a poem about human labour, emotion, suffering, and sin determined by the seasons, by Kristijonas Donelaitis, the eighteenth century Prussian Lithuanian poet and founder of Lithuanian literature.

In his later years, Kutavičius remained an exceptional, creative visionary. Even his smaller, more modestly scaled and less ambitious works became significant events in Lithuanian musical life. This is a rare case in contemporary music, when professional appreciation, the enthusiasm of performers, and the love of audiences coincide in such a way. After the restoration of Lithuania’s independence, when there were no more obstacles to the dissemination of his music, Kutavičius was able to enjoy his recognition and the attention he won from publishers and festival curators in Germany, Poland, Finland, and elsewhere, and when many recordings of his works were released by labels such as Ondine, Telos Music, Toccata Classics, Dreyer Gaido, and by the Music Information Centre Lithuania and other companies. Live festival recordings have expanded the archives of public radio broadcasters in Lithuania, Latvia, Denmark, Finland, and the Netherlands, as well as the BBC, Deutschlandfunk, Austria ORF, CBC in Canada, and others.

Kutavičius departed this world on 21 September 2021, one week after celebrating his 89th birthday. The Lithuanian music community found itself orphaned, having lost its guru, spiritual leader, and teacher. We understood then that Kutavičius’ legacy was so exceptional and influential to our cultural growth that he has become the twentieth century’s most prominent figure alongside M. K. Čiurlionis. Both are unique, with their visionary gifts, and both spent their most beautiful, productive years under Russian oppression (one in Tsarist Russia, the other under the Soviets), which prevented them from assuming their rightful place on the international music stage. Redrawing the map of cultural and political influence retrospectively will prove difficult. It is unclear whether the impactful shock of Kutavičius’ music, experienced by several generations of audiences, can sustain the same concentration of energy for new generations. One hopes it will. A testimony to this fact could be the Kutavičius Music Festival in Salzburg, under the baton of international star Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, in 2017. Gražinytė-Tyla grew up with Kutavičius’ music and sang in the Aidija Choir during her school years, under the direction of her father Romualdas Gražinis, performing many of Kutavičius’ works. In Salzburg, Gražinytė-Tyla not only performed The Gates of Jerusalem with the Mozarteum Orchestra, but also presented many other works in natural surroundings. The audience followed musical performers through Hellbrunn Park, listening to the children’s choirs of the Salzburg Landestheater and festival, and Kutavičius’ more intimate works and the children’s opera Kaulo senis ant geležinio kalno (The Old Man of Bone on Iron Hill) were performed in the open air. ‘With the works by her countryman, the Lithuanian composer Bronius Kutavičius, Salzburg Landestheater Artistic Director Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla has revealed the ancient communion of cultures… Kutavičius creates a dense atmosphere by intensifying sound through hypnotic repetitions. The effort by all the performers creates a delight for ears and eyes. Gražinytė’s hands wield precision, vitality, and a flight of fancy,’ wrote Christiane Kecekeis for drehpunktkultur.at. Let us hope that Kutavičius’ music will sustain its power, life, and the pulse of truth.

Musicologist Jūratė Katinaitė graduated from the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre (LAMT) in 1998 (Master of Arts). In 2018, she began her PhD at the LAMT. Between 1994 and 2020 she worked as a radio producer and presenter at LRT, where she still collaborates as a freelance opera producer and host. She regularly writes reviews and essays on the topics of opera, contemporary music, and cultural policy, and publishes interviews with musicians for the national cultural media. Katinaitė’s book Karalių Kuria Aplinka: Operos Solistas Vaclovas Daunoras (The King is Created by the Environment: Opera Soloist Vaclovas Daunoras, 2018) was awarded the Ona Narbutienė Prize. She is a member of the Lithuanian Council for Culture, the Art College of the Lithuanian National Opera and Ballet Theatre, and the State Commission of the Lithuanian Language. Between 2010 and 2017 she was Chair of the Musicological Section of the Lithuanian Composers’ Union. Katinaitė was awarded the Prize of the Lithuanian Ministry of Culture for the most relevant cultural criticism in 2006 and the Government’s Culture and Art Prize of the Republic of Lithuania in 2021.

1 The Church of the Holy Cross was confiscated from believers in the Soviet period and turned into a concert hall.

2 Works by Soviet era composers would be regularly evaluated before any public performance at so-called ‘hearings’ organised by the leadership of the Composers’ Union and censors authorised by the Communist Party.

3 Vytautas Landsbergis, ‘Žiogas ir ąžuolas saulės rate’, Literatūra ir menas, 30 December 1978, p.11.

4 Giedrė Kaukaitė, ‘Mano kelrodės dainos’ (III), https://www.7md.lt/muzika/2021-01-29/ Mano-kelrodes-dainos-III, accessed 14 July 2022.

5 Jūratė Katinaitė, ‘In Music You Should Always Ask the Question: And What Does That Mean?’ An Interview with Donatas Katkus, Lithuanian Music Link, No. 20 | January–December 2017, https://www.mic. lt/en/discourses/lithuanian-music-link/no- 20-january-december-2017/jurate-katinaiteinterview- with-donatas-katkus/, accessed 14 July 2022.