The Tenderness of the Humble

Anna-Marija Adomaitytė is a 27-year-old choreographer who grew up in Lithuania and studied contemporary dance in Lausanne, Switzerland. Her two most recent shows, workpiece and Pas de deux, were created two months apart in 2021 for major festivals in Vilnius and Geneva. The maturity of her choreography has captured attention far beyond the borders of these two countries, and the two shows reveal how an artist at the start of her career can manage at once to encompass the societal implications of her current practice and the legacy of her art, while simultaneously reshaping the issues surrounding each one.

Adomaitytė’s two dances are simple, short, and demanding, if not rigorous, in their development. Both pieces are based on a repetitive choreographic aesthetic close to abstraction, a physically committed interpretation by the performer, and a societal anchorage that explores dominations through the body. The most arresting element, however, is Adomaitytė’s vision: rather than focusing on dance or the world, she seems to draw on the effects of both of these to sketch a path towards a form of lucid attention appropriate for tomorrow’s world. Same song, new message: art can transform vulnerability into the ability to be fully present in the world, without ignoring or dominating it, and dance can lay bare the tragic tensions buried in the body.

WORKPIECE

An empty, black space is lit by a grid of impersonal neon lights. In the centre stands a woman in an impeccable red polo shirt and straight black trousers, her hair smoothed back in a ponytail and her face impassive, but not closed. She is on a treadmill. If you passed her on the street, you would not spare her a second glance, but here, her calmness and clothing clash with her surroundings.

She looks directly out at the audience, her gaze sweeps from left to right across the stalls. The treadmill starts, so she begins to walk. Walking is a practical, minimal movement, very different to dancing. She never gets anywhere, but she never stops walking. She is driven on by the machine. The machine, initially barely discernible, gradually gets louder. Its sounds vary constantly, as though our awareness of each of the machine’s workings is heightened in turn – the friction of the motor, electrical crackles, each footstep. The woman walks faster as the treadmill speeds up. It becomes clear that this is no exploit, merely an ordinary, incidental, routine. Her sweeping left-toright gaze becomes mechanical, her head turns in time with her steps. The young woman, whose face remains expressionless, begins to swing her arms in time with her steps. Her forearms rise horizontally, then her fingers quiver as though activating who knows what. Her hands jerk repeatedly. The movements, which have also become automatic, are so stripped of intention or ambition that their cause is uncertain. Nervous agitation? Or the automated movements of an assembly-line? The treadmill is now moving very fast. The woman’s face stays as placid and patient as possible until the final blackout, when the treadmill is heard to slow down.

workpiece was created in July 2021 at the Vilnius New Baltic Dance Festival. The programme said that Adomaitytė’s choreography drew on a year of experience working at McDonald’s and interviews with colleagues.

PAS DE DEUX

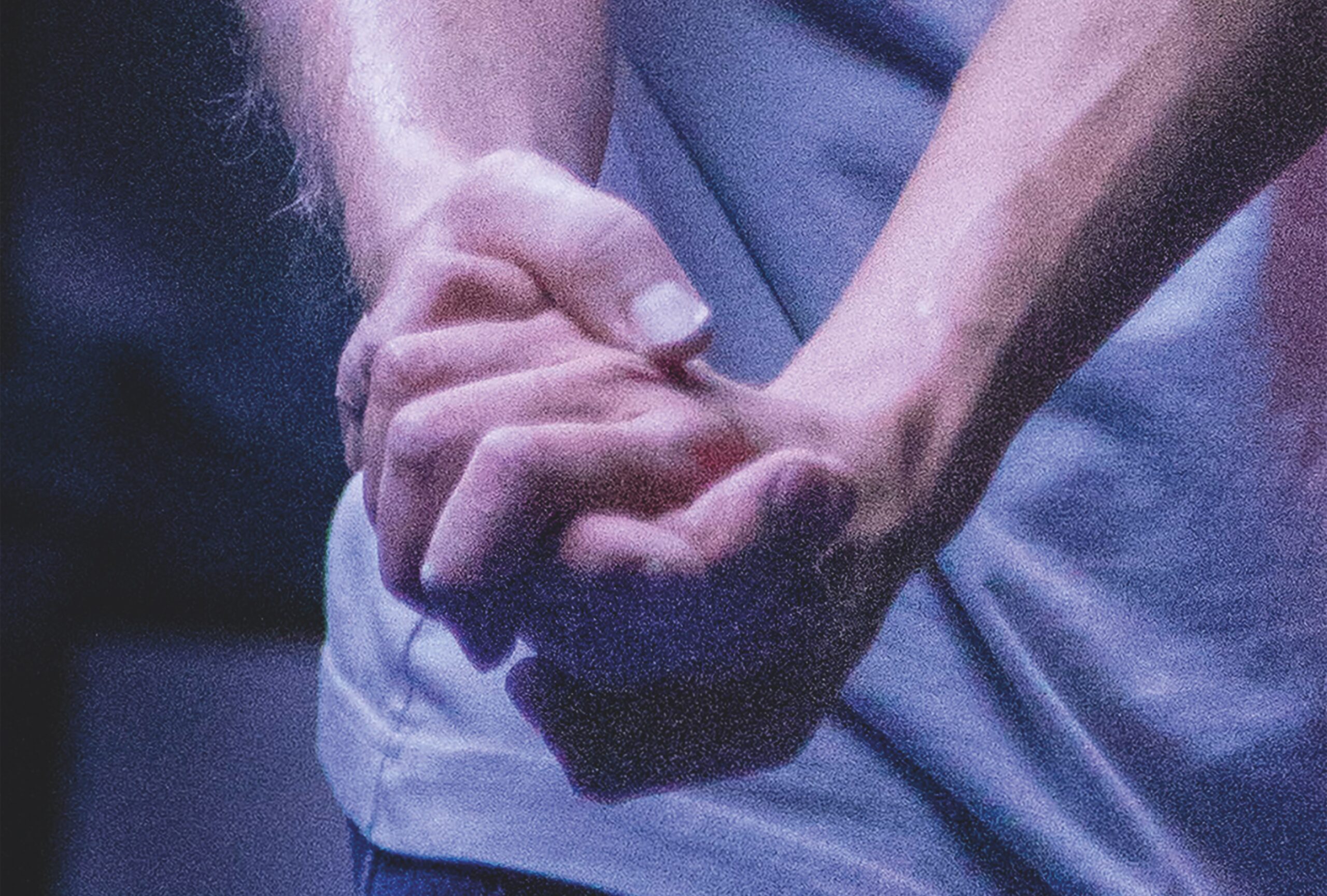

A space as large as a bedroom with an electric blue floor and a ceiling of three blocks of cold, flat light. There is a young heterosexual couple in the middle of the space. The woman’s back rests on her partner’s torso and the pair remain perfectly still, hand-in-hand, arms straight and tense, and the man’s other hand on the woman’s waist. The audience is arranged around them in two rows.

Overpowering electronic music begins with a four-four beat. The music never stops, although its rhythmic sequence becomes denser and denser, as though indifferent to the bodies in the space.

The bodies themselves remain perfectly still for several minutes. Perhaps they are enlaced, stupefied by desire? Or perhaps, on the contrary, the couple are separating, maybe fighting? Or is this a pause in a danced duet? They could almost be frozen, but then the woman rises onto her points, and the man begins to spin her around. They start to move in time but barely leave the floor, turning lightly together with each slight jump. It is as though their attempts at the skilful leaps of a classical Pas de deux are failing. They continue for almost half an hour. Their relationship becomes increasingly ambiguous. Are they seeking each other? Fighting? Or trying out dance figures together? It is impossible to know who is leading who, or what. They are caught up in a movement that connects them, although they do not determine it themselves. Sometimes they are still. Then, their breath, sweat and tired muscles become obvious and cause small tremors – unless they are keeping pace regardless? They are power, they are time, rhythm, jerky movements – and, in the pauses, perhaps a human element grasps them through what cannot be controlled.

A final pause causes a rupture. They move slowly, often out of sync. They turn about each other as though fixed, statue-like, or even maladroit and uncertain. They seem to be discovering themselves, or exploring another way of being together, without managing to find it. Unless this is the coda to a romantic duet, like one from the nineteenth century, where two performers spin together, performing multiple, never-ending lifts. Soon, the couple disappear into the darkness of a night of exhaustion and extinction, or perhaps to grapple again.

Pas de deux was created at l’Abri in Genève for the La Bâtie festival. A Pas de deux is a sequence in a ballet traditionally danced by a man and a woman. In classical ballet, the male dancer merely acts as a foil to highlight the technical skill of the female dancer, until a virtuoso finale, which they dance together. In French, ‘un pas de deux’ also describes a relationship of complicity between two people; however, ‘pas’ also means not, so the phrase could also mean, ‘there are not two’.

Two bodies in a humble being

Tackling two apparently unconnected themes – the ordinary world of work and a couple’s relationship – Anna- Marija Adomaitytė embarks on the same process of duplication and reversal. The process seems ultimately tragic, but is, first and foremost, a representation of the humble, a being without qualities, anybody.

Both shows actually reveal two bodies in one, one symbolic and the other vulnerable. The first is a social body, revealed through the existence of a norm or standard that limits the development of relationships to others throughout the dance. workpiece addresses the social norm of work to be done or standardised productivity. This is initially tackled through the walking, which evokes continuous effort, and then through the repeated movements. It can also be discerned in the unrelenting walk towards us and arms continually pointing at us, as if trying to grasp, hold or serve something. In Pas de deux, the social body lies both in the heterosexual couple and the convention of a danced duet, in which the man exhibits the woman.

The second body in both pieces is that of the individual with its characteristics and abilities. However, the shows depict humble, even vulnerable beings. These beings appear to show willing when dealing with the strict rhythms imposed on them, never expressing irony or refusal. The body in the solo needs to find harmony with the machine and with the regular and abrasive rhythm of endless production. The duet shows how two bodies define each other, with one being vulnerable to the other (i.e., seeking the other while also subject to tension within its relationship with the other); however, the bodies are also vulnerable to themselves, subject to fatigue, i.e., something other than ideas, ideals, and normative abstractions.

It is clear from the scenographic devices: these shows create representations of these divided beings. Creating the representation, therefore involves detaching the being from its abilities (from what it does) to create alternative connections with whatever powers feed those abilities. These powers are thus exposed, and it becomes evident that the being is capable of more than it does. It is not a question of strength, but of projecting into a capacity that is deferred, waiting.

External criticism and internal resistance

It should also be noted that in both cases, the socio-critical dimension of the show is externalised, i.e., contained in the title and the texts that accompany the show – adverts, presentations, and programmes. As such, this framework for analysis becomes the first part of the show, the signs created resonate with these indications.

But another process gradually comes to the fore. The rhythmical precision of the performance, the repeated movements with minimal variations, the full continuous sound, and the dim fixed lighting form a path to a type of abstraction and then a strange physicality, which arises as much from the melodic as from the fluid material whose haunted transformation is engendered by elementary, vital energy. This second phase corresponds more or less to the second half of the shows, in which the movements require more sustained attention from performers and audience alike. This marks a form of internal resistance: it reflects an ability to shoulder the burden without being overcome, to access something beyond the norms and imposed rhythms, as though those aspects have been incorporated and appropriated from the inside to enable each being to become other.

By holding both tension and attention and by clearing a space between the distant critic and interiority, the performers and audience members who commit to it are able to find a new way of being, as free, elusive and vibrant as a dream.

A place where dominations have no hold

I do not know what to call this space and way of being, unless perhaps tragic or metamorphic, because they require individuals to be torn between a standardised social existence and interiority, without abandoning one or the other, while also requiring trust in the future.

Either way, an astonishing moment is created, during which dominations diminish – dominations that freeze differences, orders, and the pulsing, empty, ahistorical time of production and convention. As these dominations diminish a gateway is created to a horizontal form of attention, in which there is no evaluation, merely movement from point to point with minimal but decisive energy. Yet again, these shows create a physical rather than conceptual image: the reasons behind the performers’ movements gradually cease to come from above – from an order, machine or convention – and begin to enter their bodies, their concentration, and their energy. I believe that the audience’s attention graduates from a ‘reading’ of the show towards a form of floating attention that evokes memories, thoughts, dreams, and fears and circulates from one to another without hierarchy. These internal movements are all the more volatile because they respond to minor signs, to gestures so miniscule that it is not clear whether they are voluntary or not: a fleeting expression in the eyes or the face, or a tremor in a hand or limb that might as easily result from a remarkable performance as from intuitive movement. I believe that the lack of variation in the movements and the full dense sound cause audience members’ minds to connect with their internal spaces, with their empathy for the beings depicted (more than mere identification or critical appreciation – the situations seem to me to be too voluntarily formal for that) and with their logical distance from, or mistrust of, the show, which rather than opening up continues doggedly to pursue its aims.

The third path to vulnerability

I saw performances of these shows in Geneva in autumn 2021, more than a year after the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. Life was almost back to normal. Most of us had had two vaccinations and the majority of public spaces were open. However, it was impossible to ignore the horrendous inequality internationally in terms of access to health solutions, all too reminiscent of the mediocrity of international actions to deal with the climate crisis, which also affects everyone everywhere.

I am writing this in Switzerland in summer 2022. Ukraine has been subjected to Russian military aggression for over five months now, China, moving on from Hong Kong, is now threatening Taiwan, the US Supreme Court has revoked the fundamental right to abortion, health services are at breaking point, and there is a very alarming drought. Meanwhile, the crudest forms of populism are finding unprecedented success and the financial markets are doing pretty well.

I am forced to conclude that the position of witness, which has been so decisive in the art world since 1945, is no longer tenable. I cannot look towards Africa, Ukraine or the Pacific and reassure myself that I am one of the few who knows what is right and just, someone with a sense of history and a feel for the path to emancipation. I can no longer cultivate a sincere feeling of beautiful empathy – although I certainly feel it, that is hardly the point – for the victims of the various horrors I see on my screens. I sense, at the limits of my own reasoning and what I am capable of formulating, that a third path is needed; one of change in myself, my consumption and my connections; change in the systems I am subject to and to which I contribute automatically, yet can only partially control – even if I still believe in debate and political action, but less in economic development.

Beyond any simple critical expression, I believe that Anna-Marija Adomaitytė’s shows enact this need, feeding into its most fundamental and difficult component: trust. Trust in whoever transforms limitations, trust in the tools handed down in the past, trust in personal change, and lastly trust in an enduring vulnerability that eludes judgement, ignores hierarchy, and is open to the fleeting nature of time and what is to come. These pieces of choreography are short, simple, and humble in the anti-heroic sense. They are free from virtuosity without refusing technicality, and I believe that they create two crucial conceptual and physical experimental spaces that open a path to an alternative time. We should not lose our lucidity about forms of oppression, but equally those forms of oppression should not be allowed to dictate a way of life and our actions by deflecting any struggles that are too unequal fully to inhabit the house of change, the house of the vulnerable, the house of those who do not forget and radically welcome what is coming.

Eric Vautrin is a dramaturg of the Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne in Switzerland. He holds a PhD in performance studies, and was previously an associate professor in performing arts studies at the University of Caen-Normandie in France. Vautrin is also a theatrical and choreographic critic and cultural writer. His research focuses on contemporary theatrical performance and how it enacts its own relationship to its audience.